Amritsar, PUNJAB:

A community historically considered to be “half Hindu” and “half Muslim” has lost its vibrant tradition in the city of Amritsar.

Amritsar :

As battle lines are being redrawn and strengthened over borders, many shared and eclectic cultural practices and spaces in the subcontinent are forgotten. Certain stories are being gradually erased from the shards of memory and history.

In the month of Muharram this year, on the day of Ashura, I decided to recover the lost narrative of Hussaini Brahmins – also known as Dutt/Datt/Datta Brahmins – and their intimate connection with the taziya procession in the city of Amritsar. In the pre-Partition days here, the taziya juloos, a grand public commemoration, would not start without the presence and participation of Hussaini Brahmins.

Before 1947, my grandfather, Padma Shri Brahm Nath Datta ‘Qasir’, a Hussaini Brahmin and a well-known Urdu-Persian poet, would initiate the taziya procession in Farid Chowk, in Katra Sher Singh, in his beloved city of Amritsar. There was a prominent Shia mosque in the area from where the taziyas were commenced and brought to the historic Farid Chowk.

The grand procession would then move towards the Imambara and Karbala maidan, near the Kutchery, which was a meeting point for all the processions coming from several imambaras. The final convergence of the taziyas was momentous. It is believed that this was close to the pivotal site, known as Ghoda pir, where the legendary steed, Zuljanah, of Imam Husain was said to have been buried.

Hussaini Brahmins: bringing two cultures together

In pre-Partition Amritsar, the taziya procession would start only after the Hussaini Dutt Brahmins lent their shoulder to carry the taziyas forward through the city. In 1942, Dr Ghulam Nabi, a prominent dentist of the city who had a clinic in Hall Bazar, rushed to the first floor of my grandfather’s house in Katra Sher Singh at Farid Chowk. He was from the Shia community and a close friend of my grandfather. He said with urgency, “Dutt Sahib, we are all waiting. Aap kandha doge tab taziya uthengee.”

A community which was historically considered to be “half Hindu” and “half Muslim”, the Hussaini Brahmins traditionally brought two cultures together. Often referred to as either Shia Brahmins or Hussaini Brahmins, phrases such as “Wah Dutt Sultan, Hindu ka dharm, Mussalman ka iman’; and ‘Dutt Sultan na Hindu na Mussalman” became a part of folklore.

Mohammad Mujeeb, the distinguished historian writes, “they [Hussaini Brahmins] were not really converts to Islam, but had adopted such Islamic beliefs and practices as were not deemed contrary to the Hindu faith.” Family narratives reveal that the name of Imam Husain was recited during mundans of young Dutt Brahmin boys, and halwa was cooked in the name of bade (Imam Husain) at weddings. Until the Partition in 1947, the Dutts were commonly called Sultans in different parts of the subcontinent.

The genealogical map of Hussaini Brahmins covers their settlements in Kufa in Iraq around the time of the historic Battle of Karbala (680 A.D.), and later in Balakh, Bokhara, Sindh, Kandahar, Kabul and Punjab. Their scribal and military traditions and commercial and marriage networks attached them to regional courts during the 17th and 18th centuries and they were mostly found in Gujarat, Sindh, Punjab and Northwest Frontier.

It was in this context that many Hussaini Dutt Brahmins expanded their influence into the city of Amritsar. For instance, historical evidence testifies that before the accession of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, Mai Karmon Dattani, the wife of a leading Dutt, was appointed the ruler of Katra Ghanaiyan in Amritsar. She was reputed to have presided over her court, dispensing even-handed justice at a public place which has been immortalised by her name, and is known as Mai Karmun ki Deohri, later a prominent bazar (known as Karmon Deori) in the city. She is remembered as the “Joan of Arc” of Amritsar.

However, what is most remembered in history is the historic link of the Hussaini Brahmins with Karbala in Iraq, as underscored by British ethnologist Denzil Ibbetson. T. P. Russell Stracey in 1911 provides a fascinating account:

“From the Kavits of the clan, it is evident that the ancestors of the Datts were once in Arabia. They participated in the Karbala War between the descendants and followers of Hazrat Ali and Yazid Sultan, the son of Amir Muaviya. They were friends of Hasan and Hussain, the martyred grandsons of the Prophet, the incidents connected with which furnish the material for the passion play of the Shias at every Muharrum.

When these princes fell, a brave warrior of the Datts named Rahib, resolutely but unsuccessfully defended the survivors. The slaughter of his band, however, compelled him and the small remnant to retire to India through Persia and Kandahar.”

Legend has it that on his return from Arabia, Rahib Dutt brought with him the Prophet’s hair, which is kept in the Hazratbal shrine in Kashmir. Nohas and Kavits, recorded in local vernacular histories, oral narratives and British ethnographic literature, endorse the glorious appeal of Karbala and Muharram among Hussaini Brahmins:

“Laryo Datt [Dutt] dal khet ji tin lok shaka parhyo

Charhyo Datt dal gah ji Garh Kufa ja luttyo.”

(The Datt warrior alone fought bravely in the field,

and plundered the fort of Kufa.)

“Baje bhir ko chot fateh maidan jo pai

Badla liya Husain, dhan dhan kare lukai.”

(When they won the field, the drum was beaten;

Husain was avenged and the people shouted “bravo”, “bravo”.)

“Rahib ki jo jadd nasal Husain jo ai

Diye sat farzand bhai qabul kamai.”

(The seven sons of Rahib (Datt) throwing in their lot

With the faithful few on hapless Husain’s side,

Died as Datts fighting, deeming their death

But friendship’s welcome sacrifice.)

Finally:

“Jo Husain ki jadd hai Datt nam sab dhiyayo,

Arab shahr ke bich men Rahib takht bathayo.”

(Off-spring of Husain! forget not thy father’s friend

Rahib, once enthroned in Arabia’s city ere thy father’s end.

Wherefore the name of Datt recite

In thy prayers to Allah, at morn and night.)

Muharram as late as the 1940s was a moment to commemorate the sacrifice of the sons of Rahib Dutt for Imam Husain. The Hussaini Brahmin was an indispensable presence on such a sombre occasion of collective and shared mourning. Partition sealed the fate of this community, as they were left abandoned on both sides of Punjab.

In Pakistan Punjab, they were seen as non-Muslims, in Indian Punjab they were perceived as being closer to Muslims. The horrific politics of the border entered the portals of my ancestral home, too. Brahm Nath Datta Qasir’s house at Katra Sher Singh in Farid Chowk, Amritsar, was set on fire by Hindu fanatic groups in 1947.

It seems there was no Muharram procession in Amritsar in 1947. At least, it didn’t happen in Farid Chowk. In the tragic transformation of Amritsar as a border city, Hussaini Dutt Brahmins were amongst its worst victims. Their fluid identity came under siege as the politics of aggressive religious identities shattered their porous cultural world.

The Dutts’ enduring link with Imam Husain, Karbala and Muharram came under threat. But all was not lost. Some of them did openly identify with their Hussaini Brahmin heritage.

Not very long ago, Indian actor Sunil Dutt, while making a donation in the Shaukat Khanum Hospital in Lahore, recorded his commitment to Karbala and said :

“For Lahore, like my elders, I will shed every drop of blood and give any donation asked for, just as my ancestors did when they laid down their lives at Karbala for Hazrat Imam Husain.”

Needless to say that Sunil Dutt was intimately connected with the cultural landscape of Amritsar too.

Ashura in Amritsar

I reached Amritsar early on the morning of Ashura, on September 10. My first instinct was to visit the Imambara at Farid Chowk in Katra Sher Singh and to trace some crucial sites connecting the gaps between Hussaini Brahmins and Amritsar. This was like looking for a needle in a haystack.

However, I was lucky to find locals who knew about the city’s pluralistic culture and gladly directed me to a lone surviving Imambara, Anjuman-e-Yadgaar Husain, in Lohgarh, just about five minutes away from Farid Chowk. Currently known as the Kashmiri Imambara, it stands on Gali Zainab (named after Imam Husain’s sister), and now renamed as Gali Badran.

As I walked into this self-enclosed, small inconspicuous structure, which houses the Raza Mosque inside its precincts, I saw a large number of policemen and the Rapid Reaction Force.

I was warmly welcomed by the caretaker of the Imambara, Syed Abdullah Rizvi, popularly called Abbuji. He told me that the structure is nearly 110 years old, and was built by Syed Nathu Shah and was regularly maintained by local Shia and Hussaini Brahmin families of Amritsar before 1947.

Abbuji was touched to meet me as a Hussaini Brahmin in the majlis. He enquired whether I had a mark of a cut on my throat (in folklore, the Hussaini Brahmins are known to have a faint line across their throats as a symbol of having sacrificed their lives for Imam Husain). The story of Dutt Brahmins was shared in the assembly (majlis):

“It was Rahib’s mother, who instructed him to sacrifice his seven sons for Imam Husain. Rahib’s mother had been blessed with seven boys by Imam Husain. As a token of her gratitude to Maula Husain, she implored Rahib to sacrifice his own sons. So he did.”

A mourner, Amit Malang, told me, “Unfortunately, Hussaini Brahmins left for Delhi and Bombay. What did they do for Amritsar?” He said sarcastically, “Aj kisi Hussaini Brahmin ki himmat hai ki voh haath kharha kare (Can any Hussaini Brahmin dare to raise his hand today?).”

His angst was shared by many who felt that the community which could have probably preserved the vibrant tradition of the city had abandoned them. Abbuji, a cementing force, a favourite amongst Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs in the congregation, said, “Imam Husain means haq (rights) and aman (peace). We want to convey this message to Amritsar.”

I then awaited the taziya procession.

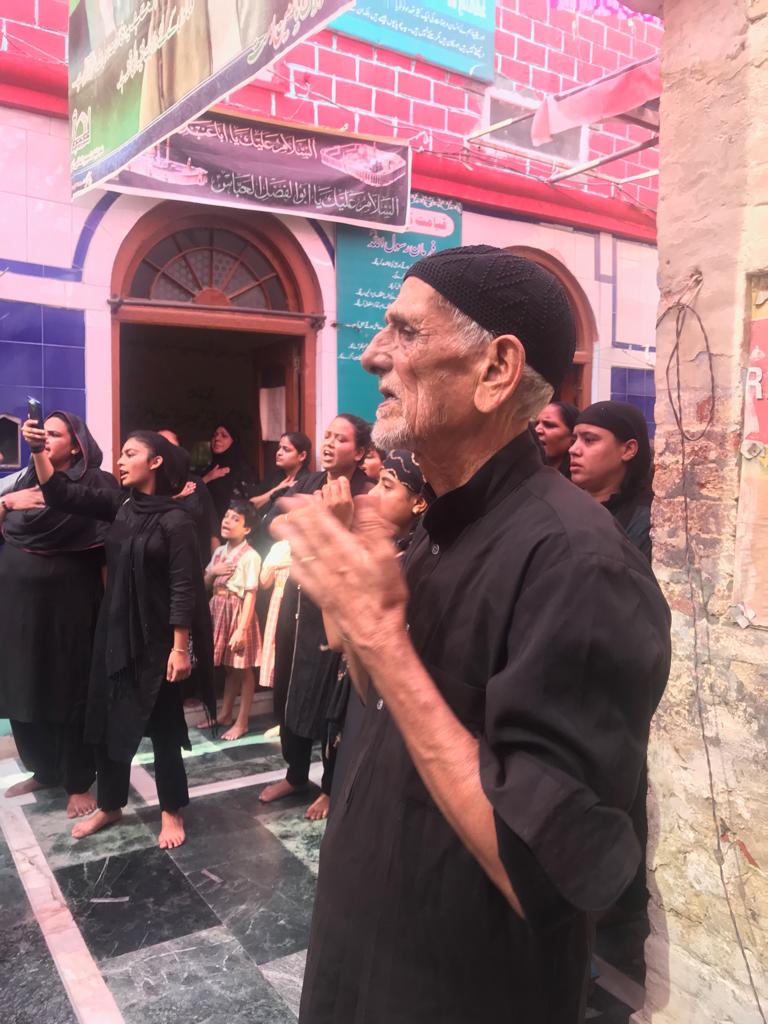

Muharram within the four walls at Imambara Amritsar on September 10, 2019. Photo: Nonica Datta

A lost narrative of Juloos-e-Ashura

“Ab koi juloos nahi nikalta. Juloos-e-Ashura Imambare ke andar hi hota hai. Muharram yahin Imambara ki chardiwari mein hota hai (Now there is no procession. Muharram is confined to the four walls of the Imambara),” Abbuji said. Zaheer Abbas, a Shia from Lucknow who has been living in Amritsar since 1980, added: “The grand shared tradition of Muharram in Amritsar was destroyed by successive wars: 1947, 1965, 1971. Partition didn’t end in 1947.”

Abbas said that the Shia mosque in Farid Chowk had been razed to the ground in 1948-49. Almost all the imambaras, over a hundred in number, were taken over (kabza) or dismantled. Abbuji added:

“Although the government took over the Karbala maidan, until recently the most prominent route for the Muharram procession was via the famous Sikri Banda Bazar to the present Imambara; taziya and alam would be brought there with much passion. But Bajrang Dal stopped it. Sunnis also didn’t support us. Now there is no procession: Ab ham darwaze diware band karke matam karte hain (Now we perform the mourning ceremony by shutting the doors and walls).”

Farhat, a sole Punjabi Muslim mourner, said that with the exodus of Hussaini Brahmins and Shias, the matam had lost its Punjabi flavour.

Abbuji asked me to write about the lost narrative of Hussaini Brahmins in Amritsar.

The openly public commemoration of Muharram in Delhi, Lucknow, Saharanpur, and even in nearby Malerkotla, Patiala, Jullundur and Jammu contrasts sharply with the slow erasure of this inclusive tradition in Amritsar. A city where Muharram was associated with the sacred geography of Imam Husain and Shia beliefs, such as Ghoda pir, Hussainpura, Gali Zainab and Yadgaar-e-Husain Imambara, the marginalisation of this vibrant cultural practice is heartbreaking.

I was shocked to see that the performance of Muharram and carrying of taziyas was confined to the four walls of a tiny Imambara under the watchful eye of the police. Perhaps, if the Hussaini Brahmins had stayed on, this would not have happened!

Around 5 pm, after “Alvida Ya Husain”, and a solemn meal of masar dal and rice – no meat is served on the day of martyrdom– I left the Imambara, lost in thoughts. I wanted to revisit Farid Chowk in remembrance of my grandfather and the eclectic community forged via the taziya procession that has now disappeared from the open spaces of the city.

I stood on the edge of Farid Chowk in Katra Sher Singh. Karmon Deori was close by; a street named after the famed warrior woman, from the Hussaini Dutt Brahmin clan, in 18th-century Amritsar, and a significant route for the pre-Partition Muharram juloos. There was no sign of any commemoration whatsoever.

As I returned to Delhi, leaving behind the taziyas and alam in the Yadgaar-e-Husain Imambara, the lament of the community of mourners almost crying for the shoulder of the Hussaini Brahmins continues to haunt me.

The reality is that the community, whose ancestors are believed to have sacrificed their seven sons for Imam Husain, has migrated to different parts of the world as global citizens. Many have simply discarded their Hussaini Brahmin identity and started to represent themselves as “Brahmins” – a construct that is miles away from what the community originally represented.

Nonica Datta teaches history at Jawaharlal Nehru University.

source: http://www.thewire.in / The Wire / Home> Religion> Culture> History / by Nonica Datta / September 30th, 2019