DELHI:

Historians and enthusiasts are taking public education into their own hands to tell the story of the country’s Muslim communities.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/6SURHLI3U5GFHIKZAHWPTRSI7Y.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/NMJCTTFTNFA4LG63XQWZD3FJZM.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/KIUTISW4DFCIJIZZWPSWFNBO7M.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/WK4SP6572FDITEWC3ZFRW4BJMQ.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/FQN33UZUQBBHFFOMZBUUHNUZRE.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/TQMPVWCPANB3TBZO3ZLBNJDYLY.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/XEMAS2AQCRCHHJFMFYRWXRCFSE.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/MZL6F5Q2ZZCWFCI5VHCGX3SYH4.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/PUNDIPNOZFDMBOW2RXK5I7E6LY.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/VSAVCCM56RGUPC7CH7QPSPAOIU.jpg)

Chaotic narrow lanes lined with opulent old mansions, shops selling spices, dried fruits and kebabs, all overhung by dangling power cables – any trip to Old Delhi, a bustling Muslim hub built by Mughal ruler Shah Jahan, is a full sensory experience.

Abu Sufyan weaves through the crowd with about 20 people in tow, making his way through streets smelling of flatbread soaked in ghee, the call to prayer at a nearby mosque mingling with the bells of a Hindu temple.

He is on a mission to change negative perceptions of Muslims by showing visitors more of their history in the capital.

“People in old Delhi were labelled as ‘terrorists’ and ‘pickpockets’ because they were predominantly Muslims from the lower economic background, and Mughal rulers were vilified as cruel invaders, as they were considered the ancestors to Indian Muslims,” Abu Sufyan, 29, says.

“My walks involve the local community members including calligraphers, pigeon racers, cooks and weavers with ancestral links in the Mughal era to showcase old Delhi’s heritage beyond these stereotypes.”

Abu Sufyan is one of a growing crop of enterprising men and women using the medium of heritage walks to educate the Indian public and tourists on the nation’s lesser-known history.

He started his walks in 2016, when hatred against Muslim communities was on the rise after Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party introduced several anti-Muslim policies.

In 2015, a BJP politician urged the local civic body in Delhi to change the name of Aurangzeb Road to APJ Abdul Kalam Road. The civic body immediately obliged, removing the reference to the Mughal ruler from the road by naming it after the former president of India, who was always considered a “patriotic” Muslim.

Later, the 2019 Citizenship (Amendment) Act caused further division, as critics said it could be weaponised against Muslims, who are designated as “foreigners” under the National Register of Citizens.

Occasionally, divisions lead to violence: Thirty-six Muslims were killed in Hindu mob attacks for allegedly trading cattle or consuming beef between May 2015 and December 2018, according to Human Rights Watch.

‘A sense of belonging and togetherness’

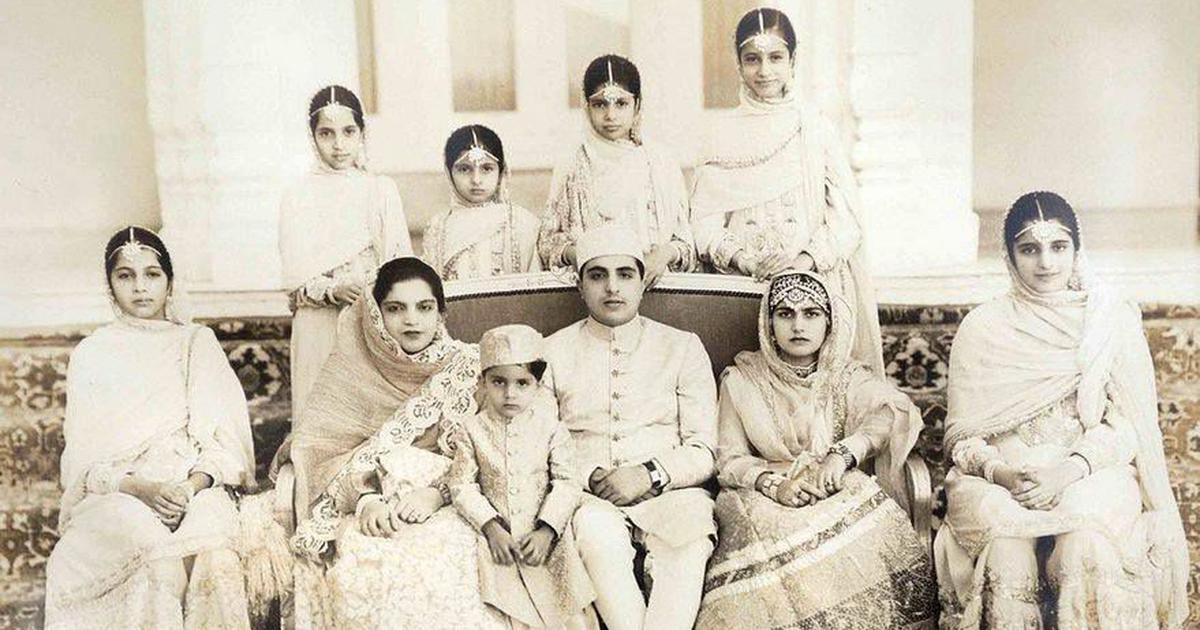

Over 2,000 kilometres away in Chennai, documentary filmmaker Kombai S Anwar hosts walks in Triplicane to tell stories of Tamil Muslim history, Tamil Nadu’s pre-Islamic maritime trade links with West Asia, the arrival of Arab traders, Mughal emperor Aurangzeb’s rule, the appointment of a Mughal minister’s son Zulfikhar Ali Khan as the first Nawab of Arcot, and the lives of the subsequent nawab’s descendants.

“Predominantly, non-Muslims participate in these walks because they are ‘curious’ about local Muslims and their heritage. During [Ramadan], they are invited to the historic Nawab Walaja mosque, where they experience the breaking of fast and partake in the iftar meal,” Mr Anwar says.

Tickets for heritage walks across India range between 200 and 5,000 Indian rupees ($2-60).

Historian Narayani Gupta, who conducted heritage walks in Delhi between 1984-1997, said any controversy related to history generates more interest.

“Whether history is right or wrong or good or bad, it has to be backed by research findings,” she says.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/DK66JSEL3NH63PKODJVBAKGCEU.jpg)

Saima Jafari, 28, a project manager at an IT firm, who has attended more than 30 heritage walks in the past five years, says it is hard to ignore the historical monuments in the city since they are almost everywhere.

Delhi-based Ms Jafari recalled one of her best experiences was a walk, in 2021, trailing the path of “Phool Waalon Ki Sair”, an annual procession of Delhi florists, who provide sheets of flowers and floral fans at the shrine of Sufi saint Qutubuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki and floral fans and a canopy at the ancient Hindu temple of Devi Yogmaya in Mehrauli.

“When I walked along with others in that heritage walk, I realised that heritage enthusiasts across religion walk together in harmony,” Ms Jafari says.

“One of the best parts of heritage walks is the storytelling that connects places with lives of people of a certain period. Plus, it always gives a sense of belonging and togetherness.”

Anoushka Jain, 28, a postgraduate in history and founder of heritage and research organisation Enroute Indian History, which holds walks to explore the erstwhile “kothas (brothels),” and “attariyas (terraces)” of old Delhi, said during pandemic lockdowns, posts on Instagram helped sparked interest.

“Before the pandemic, barely 40 people participated in two weekly walks as opposed to 50 in each of the four weekly walks which we conduct now,” she says.

But it is not all smooth sailing.

Ms Jain says some people feel uncomfortable when they are given historical facts and research that show Hindu and Jain temples constructed by Rajput rulers were repurposed during the rule of Delhi Sultanate, Qutb ud-Din Aibak.

Iftekhar Ahsan, 41, chief executive of Calcutta Walks and Calcutta Bungalow, adds that sometimes, participants come with preconceived notions that Muslims “destroyed” India for more 1,000 years – but walk leaders hold open conversations to “cut through the clutter” with authentic information.

For some, heritage walks often change perceptions.

“Until I visited mosques in old Delhi during a walk, I didn’t know that women were allowed inside mosques,” law student Sandhya Jain told The National.

But history enthusiast Sohail Hashmi, who started leading heritage walks in Delhi 16 years ago, cautions that some walk leaders present popular tales as historical fact.

A mansion called Khazanchi ki Haveli in old Delhi’s Dariba Kalan is presented as the Palace of the Treasurer of the Mughals by some walk leaders, Mr Hashmi says. The Mughals, however, were virtual pensioners of the Marathas – Marathi-speaking warrior group mostly from what is now the western state of Maharashtra – and later the British and had no treasures left by the time the mansion was built in the late 18th or early 19th century.

Another walk leader had photo-copied an 1850 map of Shahjahanabad, now old Delhi, passing it off as his own research, he adds.

“The walk leaders must be well-read and responsible enough to ensure that the myths are debunked,” Mr Hashmi says.

source: http://www.thenationalnews.com / The National / Home> World> Asia / by Sonia Sarkar / June 01st, 2023