Mumbai, MAHARASHTRA :

Sayani not only hosted Binaca Geetmala for 42 years, he produced more than 50,000 radio programmes, including the popular Bournvita Quiz Contest, and managed to transition from radio to television with seamless ease.

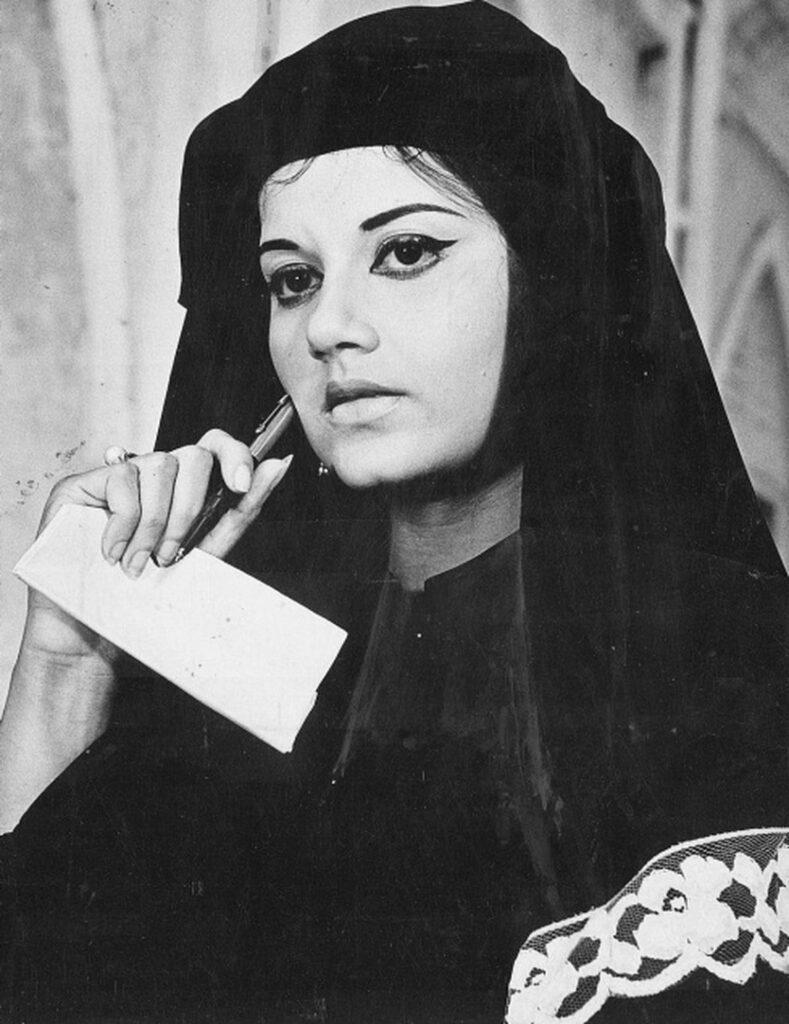

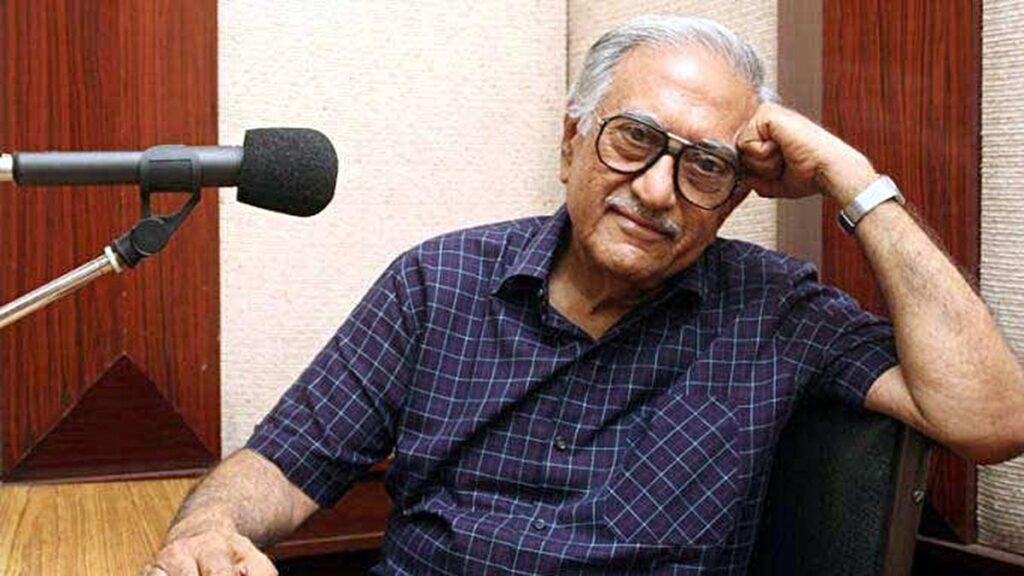

Ameen Sayani, who passed away at the age of 91 due to a heart attack. | Photo Credit: Hardeep Singh Puri-X

He painted with the spoken word and ended up filling our canvas with rich memories of his mellifluous voice and popular songs of Hindi cinema. A word that dropped off his lips got a life, a lilt, even destiny of its own. Listening to Ameen Sayani, who passed away in Mumbai following a heart attack on Tuesday evening, was like serenading joy. The Binaca Geetmala he hosted with much relish and not a little chutzpah gave millions of weary listeners of first, Radio Ceylon, and then Vividh Bharati, a reason to smile at the end of the day. For a brief while every week, from 1952 to 1994, it seemed there was no sorrow in life, and the music of life itself had an unending rhythm of its own. Until it all came to an end when Sayani, who had been battling age-related issues for a few years, breathed his last at HN Reliance Hospital, leaving his fans speechless.

The tributes came in thick and fast with Prime Minister Narendra Modi tweeting: “Shri Ameen Sayani Ji’s golden voice on the airwaves had a charm and warmth that endeared him to people across generations. Through his work, he played an important role in revolutionising Indian broadcasting and nurtured a very special bond with his listeners.” Devendra Fadnavis, Deputy Chief Minister of Maharashtra, stated, “He had an equally sweet voice as the songs.” Seasoned actor Raza Murad called him “the badshah of radio just like Lata Mangeshkar was the badshah of music”.

The praise was hard-earned. Sayani not only hosted Binaca Geetmala for 42 years, he produced more than 50,000 radio programmes, including the popular Bournvita Quiz Contest and the well-received S. Kumar ka Filmi Muqadma besides Saridon ke Saathi, and managed to transition from radio to television with seamless ease. He composed around 19,000 radio jingles, too. Such was the charm of Sayani that playback singers, music directors and film stars, all wanted their songs to be featured on his countdown show. Once renowned film director Basu Chatterjee wondered aloud what did he have to do for the songs of his films to make it to Binaca Geetmala! His prayers were answered, and the songs of both Chhoti si Baat and Rajnigandha earned repeat slots in Binaca Geetmala in the 1970s.

There is an interesting story behind Binaca Geetmala, and how some 37 years later, it became Cibaca Geetmala with a jingle announcing, “Wohi gun, wohi kaam, Binaca ka sirf badla hai naam” (same values, same work, only Binaca’s name is changed).

Back in the early years of Indian Independence, there was a pronounced effort to promote classical music. The Information and Broadcasting Minister B.V. Keskar did not have much regard or space for Hindi film songs on All India Radio (AIR). With AIR limiting itself to merely 10% for Hindi cinema, Radio Ceylon, then riding waves of popularity, stepped in with its combination of English, Tamil and Hindi music. Sayani was to make his first splash not in what was then Bombay but Ceylon.

It so happened that an American businessman, Daniel Molina, hired Hamid Sayani, Ameen’s elder brother, to run the operations at Radio Ceylon. The elder brother, in turn, brought in his sibling, Ameen, then barely 20, to host a music show. The programme was sponsored by a Swedish company Ciba, the manufacturers of Binaca toothpaste. The name Binaca was prefixed to the ‘Geetmala’. It played popular songs of the week though it would be another couple of years before the countdown started. And Sayani devised a vocabulary all his own.

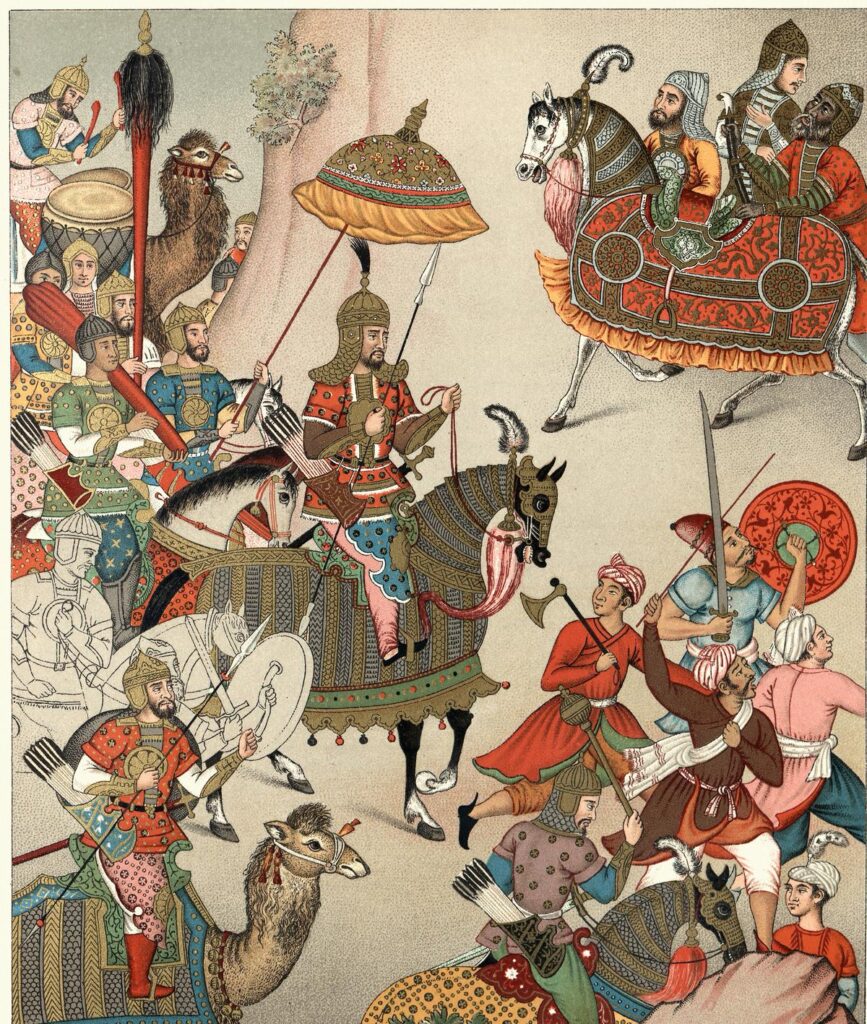

Added to his easy, conversational style were terms like ‘paydaan’ or rank. He backed it up with information about the songs and little anecdotes about the films. For instance, he told the listeners how it took 16 years to make Mughal-e-Azam, or how Lata Mangeshkar sang the songs of Satyam Shivam Sundaram at one go. Or why Amitabh Bachchan kept his hand in the pocket during a song from Sharaabi. These were little gems only Sayani, who began his programmes with trademark remark, “Behno aur bhaiyo, main hun apka radio dost Ameen Sayani”, could offer.

He played Hindi film music, the kind which was first available on LPs, then on music cassettes. Yet when he played snatches of it on radio, there was an indefinable charm. Added to the joy was anxiety to see which song would rise to the top in those rather innocent days, and his unique ability to keep the suspense going.

The show shifted to Vividh Bharati in the late 1980s before the curtain fell one last time in 1994. As a tribute, Saregama released a 10 volume compilation called ‘Ameen Sayani Presents Geetmala Ki Chhaon Mein’. It apprised the next generation with the programme’s illustrious history.

Back in the late 1970s, Jnanpith winner Gulzar had penned a timeless song, ‘Naam gum jayega, chehra ye badal jayega, meri awaaz hi pehchan hai’ for the film Kinara. The song, a regular on Geetmala, was widely played at the demise of Lata Mangeshkar. One could play it again for the matchless Ameen Sayani, the Padma Vibhushan winner who gave radio a new identity altogether.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> News> India / by Ziya Us Salam / February 21st, 2024