NEW DELHI :

An online database, it is a collection of qawwalis in cinema, from talkie days to the present.

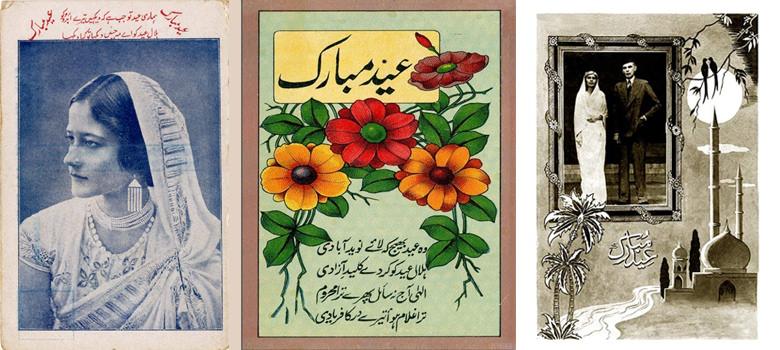

The popular qawwali, ‘Teri mehfil mein kismat azamakar’, from Mughal-e-Azam | Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

The qawwali, a musical genre closely associated with Islamic Sufi tradition, has evolved over the generations to include not just devotion, but romance, comedy and even social commentary in its fold.

Its journey from the courtly environs of erstwhile princely salons, to the dargahs, and then into the Hindi film industry, has largely gone undocumented, though the transition is still in progress. However in recent weeks, the Cinema Qawwali Archive, an online database curated by Delhi-based independent filmmaker and researcher Yousuf Saeed, has been reviving interest in this pop culture import.

“Qaul means a saying or spoken phrase [in Arabic and Urdu]. Those who sang a qaul were called qawwals. All qawwali lyrics may not necessarily send you into a trance, some can also be subtle. But the singing style is surely bold. Off-hand, most people can recall only around 10-20 qawwalis in Hindi cinema, but the actual number is much bigger,” says Saeed in a phone interview.

‘Parda hain parda’ from Amar Akbar Anthony

Working on the database for a decade, Saeed has compiled 800 qawwalis so far, with the earliest going back to the 1930s, and latest, until 2022. “The ‘talkie’ pictures came to India in 1931; though the original movies from the early 1930s are lost forever, I did manage to find some from 1936, with unusual names like Miss Frontier Mail (starring ‘Fearless’ Nadia), and the 1939 film Brandy Ki Botal,” says Saeed.

Poetry of the past

Saeed began noticing the qawwali’s ubiquity in Hindi films while working on a series of documentaries on Sufi poet and musician Abul Hasan Yamin-ud-din Khusrau, also known as Amir Khusro (1253–1325 AD). “I realised that quite a few of his qawwalis had been lifted and modified for Hindi films, so I started noting them down, and soon, the list grew to 400 songs. I wanted to make them available on a common database in chronological order,” he says. Among these is the qawwali ‘Zihale Miskin’ sung by Lata Mangeshkar in Ghulami (1985). A simplified version of Khusro’s original, the lilting composition retains the poet’s penchant for multi-lingual lyric arrangements.

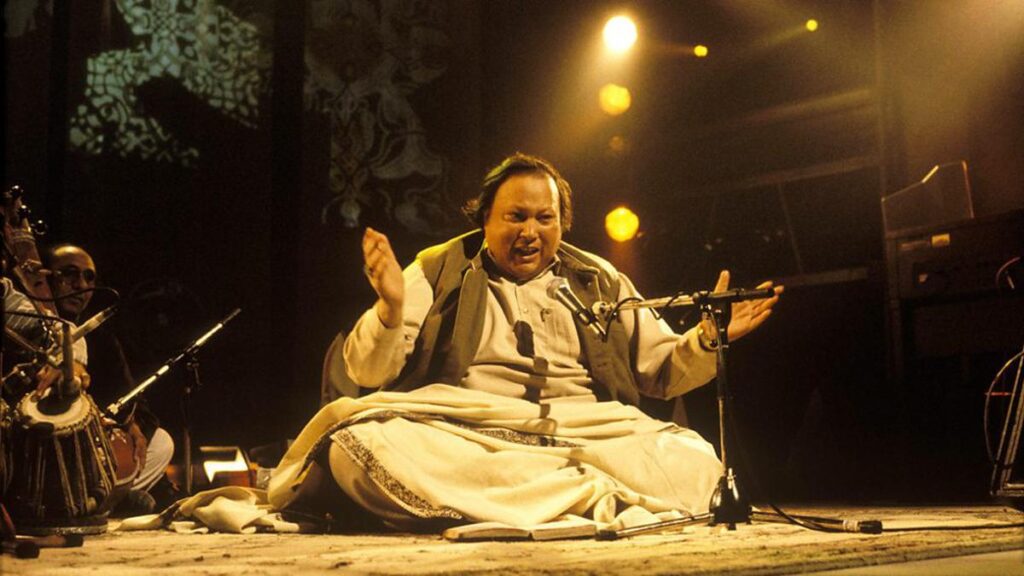

The inimitable Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan | Photo Credit: Getty Images

“’Zihale Miskin’ is very popular, and unusual, because it has one line in Persian and one in Brij Bhasha. Then there are many of Khusro’s Dohas (couplets) that are used in qawwali songs quite often,” says Saeed.

Qawwali, says the filmmaker, is a free-floating art that allows singers and lyricists to combine several genres and poetic forms in a seamless composition. Besides YouTube, Saeed has picked out his selections from DVDs and VCDs (remember those?). “I haven’t had a problem with copyright so far, since quite a few of the songs are already in the public domain. But it’s amazing how I keep discovering new qawwalis everyday. My latest is ‘Shikayat’ from last year’s Gangubai Kathiawadi,” he laughs.

Qawwali down the ages

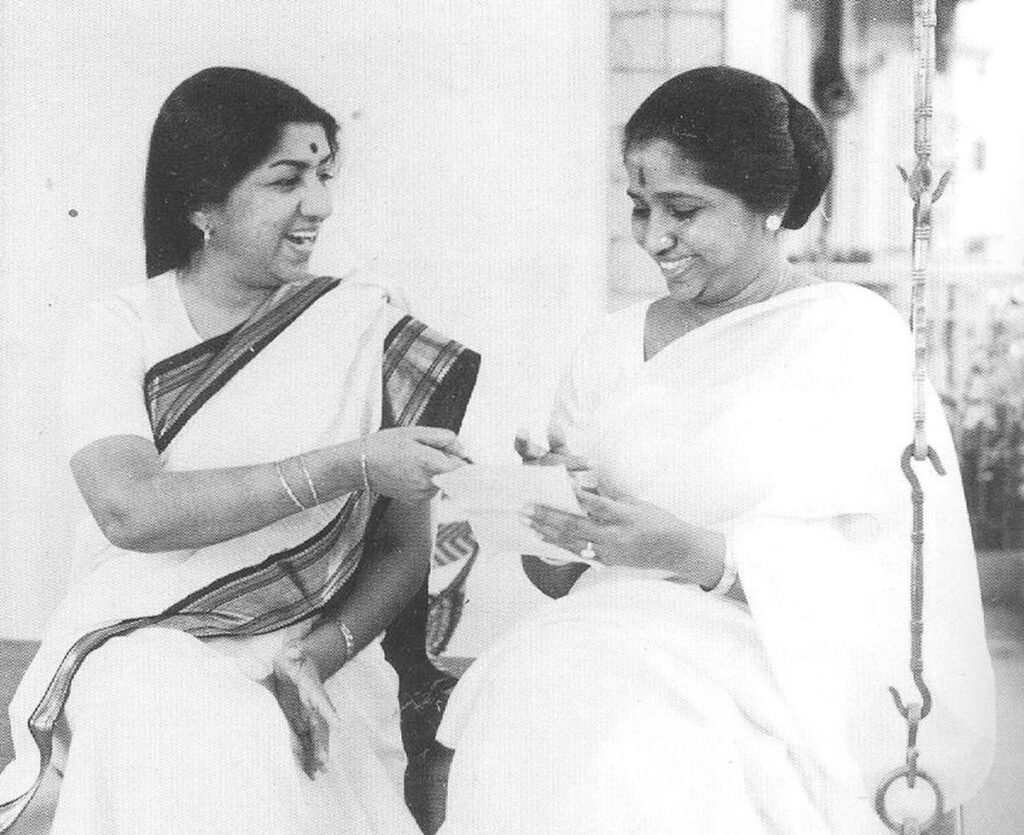

Lata Mangeshkar and Asha Bhosle have sung some popular qawwalis | Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

Saeed categorises the film qawwali of the 20th century into three periods. The first starts with the black-and-white films of the 1940s until the 1950s, when the lyrics showcased a literary flair for Urdu, by adding ‘ghazals’ into qawwalis. The second stage starts with the coming of colour films, when the qawwali too literally added some hues to its own repertoire. “A lot of things were happening in the 1960s, ‘70s and ‘80s, when qawwalis became more of a device to move the plot ahead. In some films, for example, a qawwali would be staged to highlight comedy, in the backdrop of a fight sequence, or to convey romance between characters,” he says.

The mass entertainer Amar Akbar Anthony (1977), for instance, uses the qawwali both for fun (‘Parda hai parda’) and spirituality (‘Shirdi wale Sai Baba’), to good effect.

The third phase started in the 1990s, when Pakistani singer/songwriter Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and India’s A.R. Rahman brought in sea-change by modernising the qawwali with electronica and smooth singing.

Teri Mehfil Mein | Lata Mangeshkar, Shamshad Begum | Classic Duet | Mughal-E-Azam | Bollywood Song

Comment on society

Yousuf Saeed | Photo Credit: Sandeep Sharma

The qawwali has become a social marker of sorts in films, says Saeed, creating a Muslim stereotype where the singers wear slanted fur caps, a kerchief around their neck and clap in a certain style. The Bollywood ‘Muslim social’ film that featured stories with veiled damsels courted by sherwani-clad gentlemen (Mere Mehboob, 1963) was born out of this need to appeal to family audiences from this community.

Nutan in the famous qawwali, ‘Nigahen milane ko ji chahta hai’ from the film Dil hi to hai | Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

Female singers have also had strong showing in this genre, from ‘Aahen na bharin shikve na kiye’ (Zeenat, 1945), and ‘Aaj teri mehfil mein’ (Mughal-e-Azam, 1960) to Shikayat’ (Gangubhai Kathiawadi, 2022), all showcasing the skills of chanteuses Sudha Malhotra, Lata Mangeshkar, Asha Bhonsle, Shamshad Begum, and Archana Gore.

Linguistic gymnastics

The Cinema Qawwali Archive also helps visitors to understand the literary changes over the years. “It’s inevitable that the linguistic purity of the early qawwalis is no longer there. But new words like ‘Maula’ and ‘Allahu’ and Arabicised Urdu have become more common in film qawwalis, especially as a choral element. Off the screen, in private qawwali mehfils, singers are often known to sing certain words or phrases again and again on the patron’s farmaish (request) for him or her to attain ecstasy,” he says.

Music director A.R. Rahman gave qawwali a distinct twist with Turkish, Moroccan and Syrian Sufi rhythms. | Photo Credit: RAVINDRAN R

Rahman’s infusion of Turkish, Moroccan and Syrian Sufi rhythms into his songs has helped the qawwali reach out to both the South Asian diaspora and Westerners, says Saeed. “The film Rockstar (2011) made qawwali singers at Nizamuddin Dargah famous, with tourism developing around the shrine. But interestingly, cinema has also used qawwali for its own purpose, by taking it into a secular space,” says Saeed.

Hoping to publish a companion volume on the Cinema Qawwali Archive soon, Saeed says, “People think that the qawwali is dying out, but this isn’t true. They will continue to be written and performed because film directors find it a very fascinating and unique form. Qawwali weaves the story together and keeps it going.”

ROCKSTAR: Kun Faya Kun (Full Video Song) | Ranbir Kapoor | A.R. Rahman, Javed Ali, Mohit Chauhan

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Entertainment> Music / by Nahla Nainar / July 10th, 2023