Phagwal, JAMMU & KASHMIR / Mumbai, MAHARASHTRA :

In the centenary year of Allarakha’s birth, his son talks about their music school and carrying forward an immense legacy.

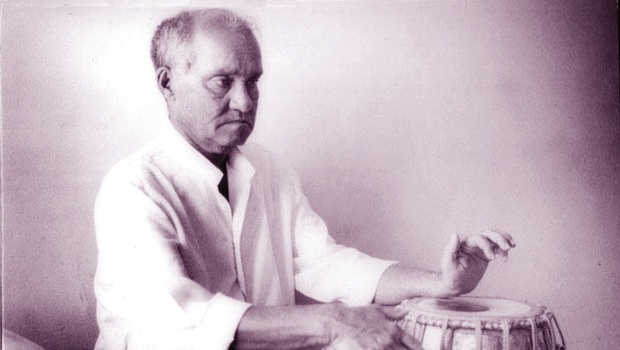

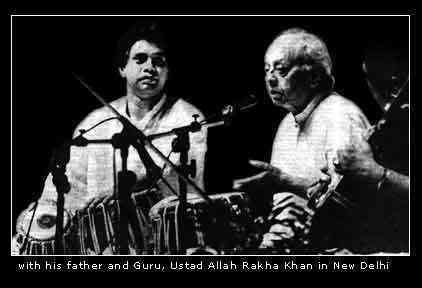

This year marks the 100th birth anniversary of arguably one of the greatest tabla players of all time – Ustad Allarakha. Born on April 29, 1919, in Phagwal, Jammu and Kashmir, Allarakha’s passion for music and talent came to the fore when he was only 12. During his many successful decades on the stage, he accompanied several of India’s most proficient musicians. His jugalbandi with sitar maestro Pandit Ravi Shankar is perhaps what he is most remembered for.

Allarakha was also a singer who composed music – under the family name AR Qureshi – for close to 40 films. He spent several years teaching in America and Mumbai, where he started the Ustad Allarakha Institute of Music in 1985.

His son Fazal Qureshi, an accomplished tabla player in his own right, now runs the institute. Classes are held in a large room in the Gala Building within the Mahatma Gandhi Memorial Swimming Pool complex in Shivaji Park. I remembered the institute from having shot a scene there for a documentary film I was making on Guru Dutt in 1989.

I returned to it last December. After nearly an hour of listening to the exhilarating sounds of several tablas being played together under the guidance of Qureshi, I sat down to speak with him. During a long, freewheeling conversation, he spoke about the institute’s origins, his father’s teaching style, what prompted him to take up the tabla, his memories of his father and what makes classical music a draw for youngsters today.

How did the institute come about?

My father knew DM Sukthankar and S Tinaikar, both music lovers and commissioners at the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation [then called the Bombay Municipal Corporation]. Tinaikar’s son Mahesh played the guitar and was in a band called Indus Creed. Zubin Balaporia and I played in the band too. Back in those days, Abbaji said, “Mujhe sikhana hai, kuchh karna chhahiye aap logon ko (I would like to teach the tabla, you both must help me)”. So Sukhtankar and Tinaikar managed to allot a room for Abbaji in the building over there.

The deputy municipal commissioner, GR Khairnar, was a strict and upright person – he had, at the time, demolished many illegal structures in Mumbai. He lived in the house just behind the building where we were, and he used to come and listen to my father and his students. Later we moved to this classroom.

Did your father have many students?

Yes, and for many years. Previously they would come to our home in Shimla House. At one point, my father had decided he wanted to dedicate most of his time to teaching. There were many students who wanted to learn from him, and having a classroom was a boon. [Even if he] wasn’t feeling well, he would say, “No, no, I have to go. The students are coming there.” He enjoyed teaching and because of that his students enjoyed learning.

Your father was taught in a one-to-one relationship with his guru. How did he or you find teaching to a group?

I teach about seven to 10 students at a time and I manage to concentrate on each one of them. They are at different levels, and so they are divided into sub-groups. That is exactly how my father used to teach.

[Let me tell you about how] I learned from my father. [Back then] he was so busy – he was travelling and [performing at] concerts. When he would come home, he’d just sit and practise. I would sit in front of him and play whatever he was playing. There was no question of being the student – whatever he played, I played.

You were mirroring him? Learning by imitation?

Yes, by imitation. There was no time to write the bols down. I had to learn them by heart. And properly, because the next time Abbaji was home after a tour, or the day after a concert, he would ask me to play whatever he had played. I did not always get the kaidas right, so I would [listen to] a recording of a concert in which he played that particular kaida, and study the variations. That helped me reproduce it. He would be impressed and would say, “Seekh gaya bacha. (You have got it.)”

And how old were you at the time?

About 15. I started pretty late. There’s a story behind that. There was a documentary made on my father in the 1970s by the Films Division in which you can see me playing the tabla with Taufiq [Fazal Qureshi’s younger brother]. We were just kids. After that I didn’t touch the tabla.

Abbaji used to tour America and also taught there, so some of his students would come to study here. There was a 16-year-old boy called Peter Peringer who came all the way from America to experience Indian culture. He was my father’s student and was very good. He stayed with us in Shimla House, and used to practise the whole day. I would go to school in the morning and when I’d come home, he would still be practising. I would take the tabla, sit in front of him, and play whatever he was playing, just as fast as him. Peter would say, “I practise this thing the whole day, and he just comes, picks up the tabla and plays the same thing, and as fast as me. How is that possible?” He recounted this incident to his friends in America who later told me about it.

But how did you do it?

I don’t know. The Peter incident was before my father had started teaching me. For me, it was something [that came] naturally. I was a little boy. I recently saw a video of a three-year-old playing the drums in an orchestra. A three-year old – now what does he know? But he plays as if he does.

Peter inspired me. I thought, look at this guy: he’s come all the way from America. And he’s just 16. He used to recite the bols so well. Zakir bhai [Zakir Hussain, Fazal Qureshi’s older brother] used to teach him too. He would take Peter to all his concerts and ask him to recite. Everyone was fascinated by his recitation: here’s this American who could recite almost like my father. He was so good. Sadly, Peter is no more.

Do you think there are more students today than when your father was teaching?

Of course. It’s [cyclical] – you come, you learn for a few years, and then you go because you’re already at a certain level and you want to perform on stage. Some of Abbaji’s students are now performing, including Yogesh Shamshir, Aditya Kalyanpur and Anuradha Pal. Then comes the next batch and the next. Many of Abbaji’s students are in America, and many of my students have established themselves as teachers and performers.

How many classes do you have in a week?

We have about 40-50 students in circulation. I don’t call all the students at the same time – we give them specific days. We have classes from Tuesday to Saturday. If I miss a lesson because I am on tour, then I take the class on a Sunday. I want every student to come at least twice a week. Our fee is Rs 700 a month. It’s nominal because we want people to learn the tabla [irrespective of whether they are] rich or poor. I have a blind student who comes from beyond Thane. His grandfather brings him here. I teach him by reciting the bols. He’s got very good hearing, and could play even before we met, [though] he wasn’t taught.

Can we say your teaching belongs to a certain gharana?

For the newcomers, it’s basic training like how to use the right and left hand. I have watched and learned that from Abbaji. There are a lot of students who already have some facility in hand movements.

I am not strict about sticking to one gharana – when I teach a certain bol, [in] the way my father taught me, I want them to play in that style/gharana. But some students come to me [after] having been taught in a different gharana, so I don’t really change their hand. I cannot, because that would be starting from scratch. Over a period of time the students realise there’s a certain way they need to play, so they change by themselves. I don’t have to tell them. Nowadays they can watch videos on YouTube, and observe the way bols are played by Abbaji, Zakir bhai or Fazal bhai.

How long do you think it takes for a student to perform on stage?

I can’t say, [but] I can give you my example. I started learning when I was around 14 or 15 and by the time I was 18, I was performing on stage. That’s not very much in terms of years, but remember, I was brought up in a musical atmosphere.

If I were to generalise, I’d say you need to learn for at least five or six years. You’ve got to get into the groove. A music school doesn’t teach you how to perform. You have to get out there. It’s like studying for an MBA – but then how do you apply what you’ve learned? You have to work in an office [and] learn the ropes, as they say.

A person must know how to apply their knowledge. Many of my students send me videos of their performances. I watch them and say, “Okay, here there was no need for you to play this or you played a little too long. It was not required.”

When you’re performing on stage, it’s [all about] teamwork. There is the instrumentalist and the tabla player, and together they [put up a] good performance. It’s not two performances happening at the same time – it’s one performance. You have to be in sync with each other. This is the attitude I want to instil in my students.

What is the most difficult thing about teaching the tabla?

I’m finding my way. Abbaji had his own thought process or philosophy behind the creation of a new composition, and that applied to when he was performing a kaida or rela. I am following his system because I used to ask myself how he created those variations. Analysis is important, and because of that I am able to add my variations to his compositions – I follow the same patterns.

It’s a way of thinking that’s passed on, and I’m trying to pass that philosophy to my students: I’m teaching you a variation, see how it’s created, see how you can develop it. From one variation another emerges. It’s like a chain. You need to understand how the chain is built and only then will you understand the composition. Create your own stuff later.

Does it surprise you that young people are still drawn to learning classical music in today’s fast-paced life?

No – in fact, I see more students now than earlier. If you go to a Zakir Hussain concert, you’ll see many young people in the audience.

It’s [about] that one personality who brings in the audience. In the ’70s, it was Ravi Shankar. Everyone wanted to learn the sitar because of Raviji – that he had played with The Beatles [was a big draw]. Then there was Ustad Ali Akbar Khan saab, who was a big name in sarod. Everyone wanted to learn the sarod. The santoor and the flute became popular thanks to Pandit Shivkumar Sharma and Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia. They made a good team with Zakir bhai. When they were on the stage, people went gaga over them. The tabla was already popular and with Zakir bhai, it has become even more popular.

The musician makes an instrument popular. That’s why the Rudra veena or the Saraswati veena are not very popular. It is because we don’t have a personality associated with these instruments. Why is the mandolin popular? It’s thanks to U Srinivas who was a great mandolin player. The mandolin is not even an Indian instrument, it’s a western instrument. The violin is not an Indian instrument either but it’s popular because of the personalities of the musicians who play the violin in the South as well as the North.

Pandit Ravi Shankar and Ustad Allarakha/YouTube.

This year marks your father’s 100th birth anniversary. How would you like him to be remembered?

My father was way ahead of his time. And a lot of people would agree with me. While everyone performed straightforward taals, he was creating new compositions in different rhythm cycles – he played six and a half, seven and a half, things the others were not doing. He was very innovative.

Abbaji was one of the first tabla players to accompany South Indian musicians, international drummers and classical violinists from the West. He was the first tabla player to compose film music. In later years, other classical musicians starting composing for the movies, including Ravi Shankar, Ustad Ali Akbar Khan and Ustad Vilayat Khan. Abbaji was a very open-minded musician. Despite being a traditionalist at heart, he was doing all this other stuff which was not connected to the tabla. In the 1940s, he was even employed as a vocalist with the All India Radio.

I’d like people to remember him as an all-round musician. He was a tremendous film composer. That’s one of the reasons why we created The Journey Continues, a musical tribute for my father with actor-storyteller Danish Hussain. It showcased Abbaji’s many talents.

What do you remember of him as a father?

He was a very calm and relaxed person who did not lose his temper. Taufiq and I were closer to each other in age. Zakir bhai was older. Abbaji never scolded us, [even though] we kids were up to all kinds of mischief, running amok around the house. He never scolded us. My mother would go crazy, but he would sit calmly – and let us do whatever we wanted. He had a lot of aspirations for Zakir bhai because he was the first son born in the family. It was not just Abbaji – most people around him shared his feelings. “Bhai, Ustad Allarakha ka ladka hai, pehla ladka hai, yeh to bajayega hi. (After all, he’s Ustad Allarakha’s eldest son, he is bound to play the tabla).”

Was your father an affectionate man?

He was very affectionate. And unbiased. If I was sitting among his students and practicing, he would not pay me more attention just because I was his son. He was very impartial. For him, talent was important – if you’re good, no matter who you are, rich or poor, I’ll teach you more.

What if a student is no good? What do you do?

I have to tell them – look, this is not happening, try something else. I don’t want them to waste their time or mine. If I want to be a professional musician and I am not good enough, I should realise it myself. Just because your father is in that profession, you don’t have to follow him.

When it comes to my relationship with the students, I’d like them to treat me as a friend, they should feel free to talk to me. They can ask me questions. I prefer a relaxed atmosphere – hierarchy shouldn’t exist.

How did your father deal with his students?

The older generation were very direct in telling people if they were going wrong. He used to sit in the audience and if his student was making a mistake, he would say out loud: “Arre, kya kar rahe ho? (What do you think you’re doing?)

Abbaji was outspoken. He used to think if you have something to say about someone, say it to their face, don’t talk behind their back. That’s how many great musicians were in those days.

source: http://www.scroll.in / Scroll.in / Home> Magazine> Interview / by Nasreen Munni Kabir / January 12th, 2019