KARNATAKA / London, UNITED KINGDOM :

The artefact sitting in V&A was iconic, identifiable and far away from home

The day I saw Tipu’s Tiger behind its glass case at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London was a day of significance. That morning, after months of being cooped up in Oxford, some friends and I took the train to Marylebone and found the absence of dreaming spires refreshing to say the least. At noon, a friend from India was waiting for me on the other side of the busy Camden High Street. As we hugged amidst the crush of gliding Londoners, her muffled exclamation might have been: ‘It’s so crazy we’re meeting here of all places, so far from home.’

That phrase would be borrowed by me on two separate occasions during the day. In the evening, I stood before Julian Barnes at the Royal Institution and told him how I had read ‘A Short History of Hairdressing’ over and over again to teach myself the ‘architecture’ of a short story. I felt a potent urge then to parrot my friend. It was ‘crazy’ to see and hear Barnes in the flesh, so far from my bedroom in Kolkata, the only other place he had seemed real and, dare I say, attainable through his prose and through the material object, that is, his books in my hands, the only feasible rendezvous with the man.

I had never thought then it would happen: to have someone I studied so minutely sit before me and confess he didn’t think as highly of his short prose as I did.

Iconic meeting

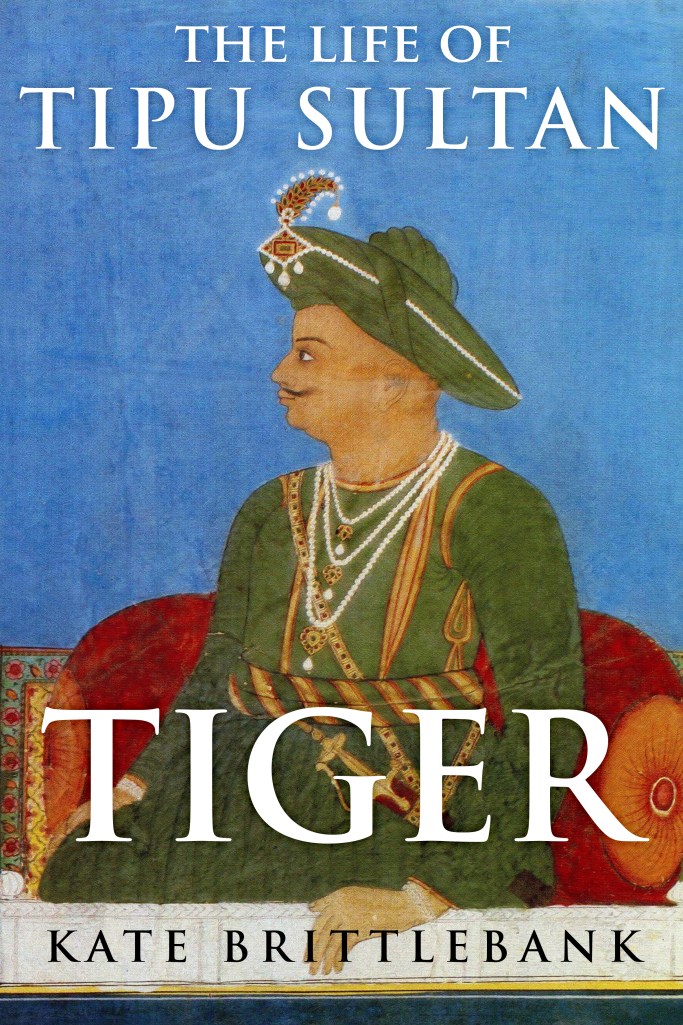

The second occasion I was inclined to echo her words that day was when I stood in the South Asia section of the V&A before Tipu’s Tiger, which had always been relegated to the Did You Know section of our history books. It was not exactly like meeting an old friend or a revered author, but it bore all the characteristics of such a meeting. Like Barnes and my Kolkata friend, it was instantly iconic, identifiable from a distance, and a ready reminder of my distance from India. In fact, standing before the wooden automaton, slightly disconcerted, I addressed it and thought: ‘You are so far away from home.’

The possible inspiration for the mechanical figure seems fitting to some. Hector Munro Jr, whose father defeated Tipu’s father Hyder Ali in the Second Anglo-Mysore War in 1781, was mauled by a royal Bengal tiger at Saugor Island in 1792 and died from the injuries. This must have seemed like divine intervention to Tipu, a wrong set right. The carved and painted, almost life-size, wooden musical automaton was created for the Sultan, whose personal emblem was a tiger and whose hatred of the British was well-known.

The last laugh

With the fall, however, of Seringapatam and the execution of Tipu in the Fourth Mysore War of 1799, the Tiger travelled from the music room of Tipu’s summer palace to the Company’s East India House at Leadenhall Street in London, where the public was given access to view and play with it.

Its wooden body with a keyboard embedded in the flank was thrown open to the English masses who came in and played ‘God Save the King’ and ‘Rule, Brittania!’ upon it. If Tipu thought he had been mocking the Englishmen with the Tiger, they were now having the last laugh.

I deal with issues of empire and post-colonial anxiety almost on a daily basis, especially in a place like Oxford, especially on a course called World Literatures in English. Of course, when I first saw it, I silently demanded a restoration of the tiger to its previous owner, to its previous nation. My anger at seeing the Tiger in an English museum, so far away from home, was justifiable. The Tiger was not borrowed. Nor was it touring, as it had to New York’s MoMA in the 50s. Instead, it was a ‘permanent’ acquisition at the V&A.

Of collaborations

For every Indian schoolchild, the Tiger, just an artefact but nonetheless awe-inspiring, was not an affordable train or flight away, like Fatehpur Sikri or Sher Shah’s tomb.

For me, the Tiger’s distance from my home was a reiteration of the national and racial distinctions not only of the Anglo-Mysore variety, but also of the Jadavpur-Oxford type that I faced every day. Besides dodging questions like ‘If you’re from India, how’s your English so good?’ for the past few months, I had had to clarify to a white friend who subsisted on the chic-ideal of Zadie Smith that India has Bengalis too, and no, I did not have relatives in Brick Lane, not that I knew of anyway.

Seeing Tipu’s Tiger that day catalysed a recollection of an afternoon in 2016 in the Victoria Memorial Hall with Thomas Daniell and his nephew William. Their tranquil scenes of India, while in stark contrast to the ferocity of the Tiger, do something interesting.

The English hands of the Daniells reproduce the Indian hands of the architects behind the buildings and locations they sketch. Their canvas becomes a surface of Anglo-Indian collaboration, similar to how it is conjectured that the mechanics of the Tiger have an Indo-French history.

This recollection, and the subsequent contemplation on collaboration, made me think of several works of restoration that the V&A carried out upon the Tiger, especially after the bombing of London in World War II. Could this act of restoration be seen as an act of reparation? Could the Tiger’s position — now behind a glass case, its crank handle inaccessible to the public — be an apology for the disrespect permitted in East India House?

The Tiger, so far from home, is an icon that reminds me of a past based on plunder and pillage by the nation it sits in. Yet, its 18th century splendour has weathered war and wear so well. Do present acts of safekeeping obliterate the violent history of its, for want of a better word, theft?

I am persuaded to wonder if the Tiger is now a collaboration between Tipu’s Mysore craftsmen and its modern conservationists in England and if I should be thankful for the restoration. Are the acquisition and conservation of an Indian object in a British museum and the works of British painters displayed in a Calcutta museum an instance of transnational collaboration and exchange? But in the case of Tipu’s Tiger, this then also begs the question: how long is too long before we forget that what is ‘acquired’ is what was once ‘removed’ from its home?

The writer, a Felix Scholar, is studying World Literatures in English at Oxford

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Society> History & Culture / by Rohit Chakraborty / May 05th, 2018