Srirangam, TAMIL NADU :

By accepting the concept of the Thulukka Nachiyar, within the temple, was a space created to locate the newcomer Muslim within the world of the orthodox Hindu?

India is a mosaic of many curious tales. But very often, seemingly incongruous elements that reside in the realm of fable and myth end up lending an ironic congruence to the concrete world of men. Throughout Indian history, whenever politics has found itself at an awkward crossroads, a generous fabrication of mythology has helped ease the process. One prominent example is Shivaji’s—the Maratha warrior had emerged as a powerful force in the late 17th century, with armies, treasure, and swathes of territory at his command. But rivals painted him merely as an over-strong rebel, so that in addition to power, what he needed was legitimacy too.

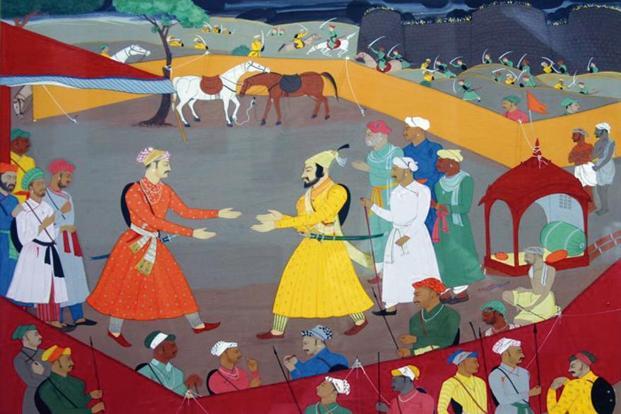

The answer to Shivaji’s woes came in 1674, when he decided to crown himself king, with classical ritual in full and extravagant display. A genealogy was invented connecting him to an ancient royal line, and retrospective rituals permitted him to take his place as a “pure” Kshatriya, when so far Brahmins had deemed him inferior in caste. It was a masterstroke: Shivaji now towered over other Maratha clans in status, while simultaneously alerting his Mughal enemies that he was no longer a “mountain rat”—he was an anointed, lawful monarch.

As a society too, India has been capable of negotiating disruptive changes through the invention of tradition. Reading scholar Richard H. Davis’ work recently reminded me of the bizarre, clever and typically Indian ways in which this was achieved. When Muslim might arrived in India in the form of invaders, a new chapter was inaugurated in the story of our subcontinent. The old order fell, and a different structure was fashioned. One way in which the elites on both sides tried to rationalize, in their respective world views, these painful changes is through what historian Aziz Ahmad called epics of conquest and resistance. Thus, for instance, we have Muslim accounts that exaggerated the “destruction of infidels”, when, in reality, even the terrifying Muhammad of Ghor’s coins prominently featured the “infidel” goddess Lakshmi, countered by Hindus with their own stories, the case of Padmavati preferring fire to the embrace of a Muslim being one such. Rhetoric was amplified on both sides, legends and tales competing for narrative dominance to come to grips with changes under way on the ground.

One such fascinating story from the 14th century features a Muslim woman recalled to this day by Hindus as Thulukka Nachiyar (literally, “Tughluq Princess”), who is said to have fallen in love with a Hindu god. The outline of the story is as follows: When Muslim troops from Delhi plundered temples in southern India, on their list was the great Vaishnava shrine at Srirangam in Tamil Nadu. Temple chronicles show that indeed idols were seized, and, in this story, the processional image of the deity is taken to Delhi. The reigning sultan consigns the idol to a storeroom, while a local Tamil woman, who had followed the troops, returns to Srirangam and informs the temple authorities of the precise whereabouts of their deity. Dozens of priests now make their way to court, where, after entertaining the sultan with a series of performances, they request the return of their lost idol. The cheerful Tughluq king is happy to grant them this, commanding his men to go to the storeroom and fetch Srirangam’s deity. Everyone is, at this point, rather pleased with the turn of events, and we have every hope of a happy ending.

This is where the twist occurs. It so happens that the sultan’s daughter had long before gone into the storeroom and collected the idol, taking it to her apartments and there playing with the deity as a doll. The implication, however, is that by dressing “him”, feeding him and garlanding him, as is done to deities in Hindu rituals, the princess was essentially worshipping the image, winning divine affection. When the appeal from the Srirangam party is heard, the deity puts her to sleep and agrees to return south, only for the Tughluq princess to wake up distraught—she hastens to catch up with the Brahmins, who meanwhile have split, one group hiding the idol in Tirupati. Arriving in Srirangam but not finding the deity even there, the princess perishes in the pangs of viraha (separation).

Her sacrifice is not for nothing, though. When eventually the deity comes home, He commands the priests to recognize his Muslim consort, commemorated ever since in a painting within the temple. On his processional tour of the premises, to this day, the deity is offered north Indian food at this spot (including chapatis).

The story is a remarkable one, with an exact parallel in the Melkote Thirunarayanapuram temple in Karnataka, where, in fact, she has been enshrined as a veiled idol. Though it seems unlikely that a Tughluq princess actually came to the south head over heels in love with a deity, could it have been that there was a Muslim woman instrumental in having idols released from Delhi? Or is it, as Davis suggests, a “counter-epic” where the roles are reversed: Instead of a Muslim king chasing after Hindu princesses, we have a Muslim princess besotted with the Hindu divine. By accepting the concept of the Thulukka Nachiyar, within the temple, was a space created to locate the newcomer Muslim within the world of the orthodox Hindu? The truth might lie in a combination of these possibilities, but we can be sure that it is a colourful, revealing narrative with a splendid cast, telling us once again that while there were moments of crisis between India’s faiths, legend and myth allowed them to see eye to eye and move on to fresh ground—a lesson we would be wise to remember in our own contentious times.

Medium Rare is a column on society, politics and history. Manu S. Pillai is the author of The Ivory Throne: Chronicles Of The House Of Travancore.

He tweets @UnamPIllai

source: http://www.livemint.com / LiveMint / Home> Explore / by Manu S. Pillai / March 30th, 2018