Mumbai, MAHARASHTRA :

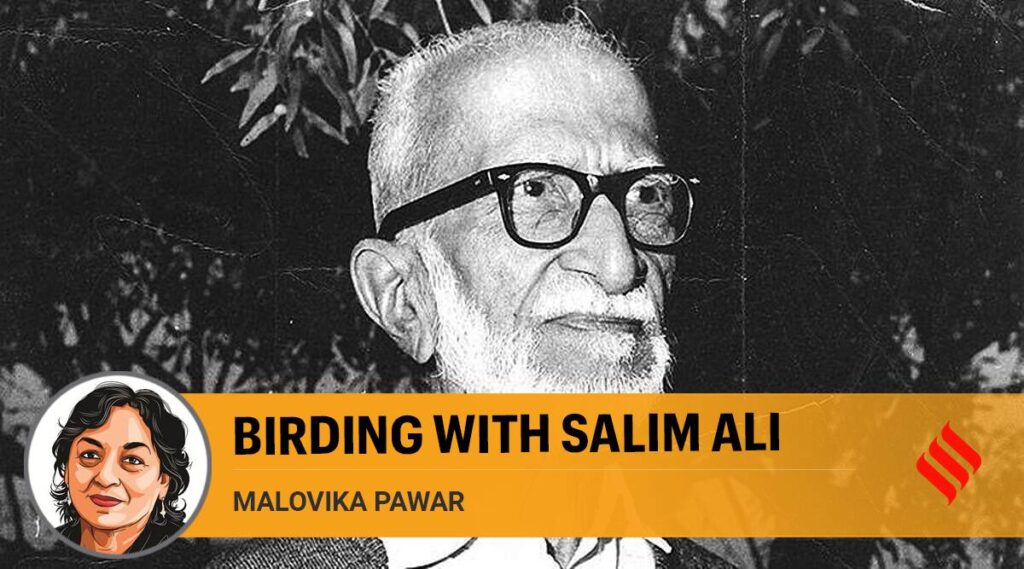

It’s the author’s well-founded belief that Salim Ali’s life offers today’s children a role model.

Here’s hope for those young people who are mediocre with mathematics and other studies, and likely to be uninterested in business. Salim (pronounced Saalim, not Saleem) Ali’s interest in birds began to awaken when he shot a male sparrow, standing guard over its mate’s nest, with an air rifle. Next morning he found that another male sparrow had taken its place, and he shot that too… This went on until he had shot eight male sparrows, and then wonderment took the place of whatever had urged him to shoot those sparrows. This wonderment gave his life a foundation of incredible strength. It enabled him to survive the loss of several salaried jobs, and, later, the loss of Tehmina, his wife, who, throughout their 21 years together, supported his efforts wholeheartedly.

This book is his life story, told simply, and for children. It’s the author’s well-founded belief that Salim Ali’s life offers today’s children a role model.

The author makes no effort to sugar-coat the story. Salim’s initial difficulties with academics are covered in some detail, as well as mediocre performance in school, and his inability, found in many others of his extended family, to run a business successfully. This mediocrity at school had nothing to with his powers of observation, though. For example, it was known that the houbara bustard he saw in Sind (now in Pakistan), under normal hot and dry conditions, has a colour that affords perfect camouflage, enabling it to hide easily in the sand. Salim discovered, however, that the bustard’s colour changes in the rains, enabling it to hide in wet sand as well!

Also included is the story of Salim’s relationship with Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen, a former British Intelligence officer. The Colonel’s claims to being a hero might have been authentic, but his claims as an ornithologist were proven false in the 1990s, decades after his death. It illustrates Salim’s naivete with people, but also warns youngsters of the possibility of charlatanry in science.

My favourite story, though, is about Salim’s encounter with a bandit in the summer of 1945. Near the Tibetan border, poking around among the bushes, he saw a bandit armed with a dagger and a rifle. Escape was impossible, so he resorted to a ruse. He had a collapsible chair, a small folding seat on a stick. He pretended that the stick was a rifle barrel, and clicked the folding seat open to give the impression that he was loading and cocking his own rifle. It worked, for the bandit fled.

So here’s proof that commitment, integrity, and hard work — combined with observation, quick thinking, and luck — will get you where a great academic background won’t. A terrific lesson for youngsters, and packaged well, to boot.

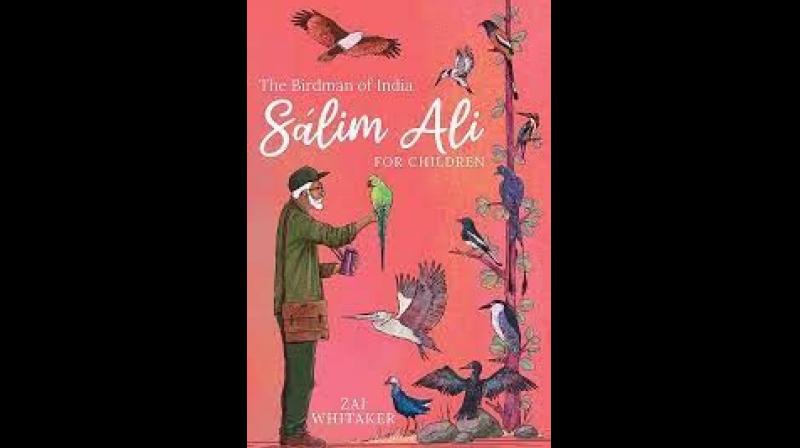

The Bird Man of India: Salim Ali for Children

By Zai Whitaker / Hachette / pp. 142; Rs 350

source: http://www.asianage.com / Asian Age / Home> Books / by Shashi Warrier / August 27th, 2023