Mumbai, MAHARASHTRA :

Glossier, more attractive birding books have been published in the 80 years since Ali’s guide first appeared, but it remains indispensable.

It is a small book, my copy of Salim Ali’s The Book of Indian Birds — a hardcover version, bound in green, a mere 187 pages. I have the 1979 edition. The cover is long gone, leaving behind a few tatters of the original, but I am hard put to think of a book I have treasured and used as much. The book and an old pair of Bushnell binoculars acquired some 20 years ago are a part of my essential travelling kit, as essential as a toothbrush and comb.

The first edition of the book appeared in 1941. Jawaharlal Nehru , a keen nature lover, gifted a copy to his daughter while lodged in Dehradun jail.

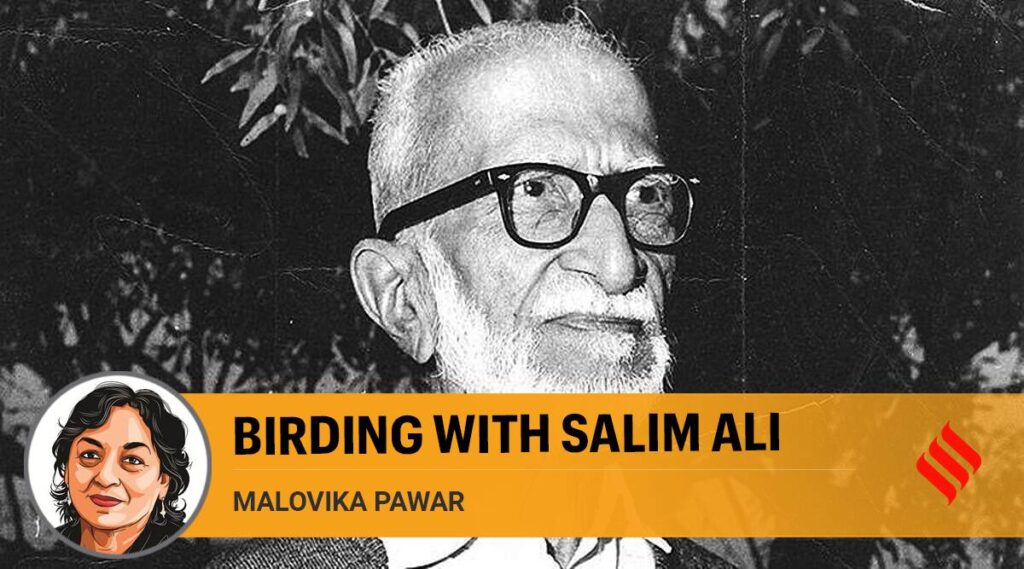

Ali was quite matter-of-fact in his autobiography, The Fall of a Sparrow. According to him, the book was “acknowledged as largely responsible for creating and fostering much of the interest in birds and birdwatching seen in the country today”. Indeed, for people of a certain generation, no other guide has been valued and loved in the same way, and even among Ali’s other classic works, it is this book that has iconic status among Indian birdwatchers. While setting off on a birding trip, we would ask each other: “Have you taken your Salim Ali?” Or: “Oh, no, I forgot my Salim Ali.” It was always the small green book that we were talking of. It is the essential — the foundational — field guide for Indian birders. It is now in its 13th edition. No other book can take its place.

I came to birdwatching by serendipity. No one on either side of my family was even remotely interested in birds. By a throw of the dice, I was allotted Bharatpur for my district training in the IAS. The Keoladeo Ghana National Park beckoned. I was hooked. Ali, who had done more than anyone alive to create this “Garden of God” out of a Maharaja’s private wetlands reserve, was still alive, and visited a few times while I was there. Two bird guides, Sohan Lal and Bholu Khan, still active today, were being trained by him and other naturalists. They were to mature into fine birding guides, much in demand.

The Book of Indian Birds is where we learned our basic vocabulary of birdwatching. For instance, we learned that “pied” meant black and white, that “rufous” meant reddish-brown as in rust or oxidised iron, and that “fulvous” indicated tawny. Every carefully chosen word signified something. The clarity and the precision of expression meant that in a short half-page entry, we would have all the necessary information about a species. Each write-up was organised around five or six points — size, field characters or appearance, distribution, habits, food, call and nesting. Size was always charmingly described as myna plus, or house crow minus, or with reference to a sparrow, a bulbul or other common bird. Under “field characters”, Ali beautifully and accurately described the appearance: Colour of the feathers, the shape of the bill, silhouette in flight. A crimson-breasted barbet was “heavy-billed”, a blue-throated barbet “a gaudily coloured, dumpy green, arboreal bird” and the common grey hornbill a “clumsy brownish-grey bird”. Birds are described variously as handsome, squat, soft-plumaged, lively, dapper, dainty, spruce, slim, perky, well-groomed. The common roller or blue jay (neelkanth) is described as a “striking, Oxford and Cambridge blue bird”.

People who have always noticed the easy readability of the prose might not be aware that Ali himself gave credit to his wife, Tehmina, for ironing out the “stilted passages” and for “moderating the language”. He did not fail to praise her “remarkable feeling for colloquial English prose style”.

My Salim Ali bears the marks of the trajectory of my life, where I went, what I did. It is not merely well-worn and well-thumbed, with an unravelling spine and precarious binding; it also bears the added signs of pickle stains and tick marks in ink and pencil. Like me, it has seen better days. I know that many bird guides have been subsequently published with much better production values and better colour plates. I am aware that many of the illustrations in the Salim Ali book are decidedly not true to life. For instance, never did a rosy pastor look as pink in real life as it does in the book. But this is mere quibbling. The core and kernel of the book is that it communicates to us so successfully the magical universe of the birds of India.

The international jury which selected Ali for the J Paul Getty Wildlife Conservation Prize of the World Wildlife Fund in 1975 said in its citation: “Your message has gone high and low across the land and we are sure that weaver birds weave your initials in their nests, and swifts perform parabolas in the sky in your honour.”

On his 34th death anniversary on June 20, it is time to remember the book that Ali gave us, which took us on this magical journey to the birds.

This column first appeared in the print edition on June 19, 2021 under the title ‘Birding with Salim Ali’. The writer is a former IAS officer.

source: http://www.indianexpress.com / The Indian Express / Home> Opinion> Columns / by Malovika Pawar / June 19th, 2021