UTTAR PRADESH :

OBITUARY

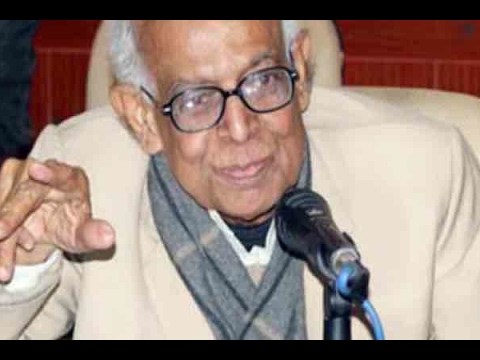

In spite of his close associations with some of the giants of Indian politics, he never became an MLC, MLA or MP. He was, in a true sense, a compassionate and dignified face of Indian politics.

IT was 10:45 in the morning yesterday when my friend and class fellow at AMU Mr Najam uz Naqvi called me to inform that Sagheer Mama had passed away at a hospital in Bareilly. The news was so unexpected that it had me shivering, too numb for any reaction. For quite some time I was stunned beyond words still trying to fully grasp the heart wrenching information perhaps very much in denial.

This was not any news of a relative’s death. It is not that unusual for us to hear about the death of someone close, but the passing away of Syed Sagheer Ahmad (Najam’s Mama) was not the death of an ordinary person. It was as if I was witnessing right before my eyes the end of an era.

Syed Sagheer Ahmad was born on the 4th of December, 1934, in the Tahseel/ Qasba Sehsawan in Badaun district. He received his education from Aligarh Muslim University, the same place from where he picked up interest in socialist politics and remained a lifetime loyalist. Janab Syed Sagheer Ahmad was not much of a public figure but he always had access to the highest echelons of power and politics. He was one of those rare young turks in Congress who had dared to revolt against the dictatorial regime of Mrs. Indira Gandhi along with Chandershekharji and Mohan Dharia.

He was an avowed socialist, a well-known and respected face among the notable socialist leaders and movements. Mrs. Gandhi personally knew him well. He was a close friend and confidant of Chandershekharji. Chandershekharji mentions him fondly in his Jail Diary. V.P. Singh knew him personally too. The two great leaders of Congress party in Uttar Pradesh, Mr. Hemwati Nandan Bahuguna and Mr. Narayan Datt Tiwari kept him close to their hearts always consulting him on critical minority issues. He often played an important role in removing misgivings between Mrs. Gandhi and her party satraps in Uttar Pradesh. He worked under patronage of giant leaders like Jai Parkash Narayan, Acharya Kripalani, Ram Manohar Lohia. He was closely associated with renowned socialist leaders like Babu Tarloki Singh, Dr. Abdul Jalil Faridi and Narayan Datt Tiwari.

In spite of his close associations with some of the giants of Indian politics, he never became an MLC, MLA or MP. He was, in a true sense, a compassionate and dignified face of Indian politics. He belonged to Muslim aristocracy in UP. However, he never used politics for personal favours. Throughout his life, he depended on his family or personal resources for his political activities and finances. He would never speak or ask for himself but for the populace, he was a firm and assertive advocate.

There are numerous persons in UP who reached Assembly and Parliament only because of his consistent backing. He neither sought nor was he rewarded for his unfaltering selflessness, sacrifice, honesty and self-esteem. Those who know Janab Syed Sagheer Ahmad would definitely agree with me that he was the greatest victim of political injustice of his time. He was not an ordinary politician or a socialist thinker. He had closely watched all the important political developments, especially in North India. He was aware of the ins and outs of political circuits.

It wouldn’t be wrong of me to say that he was a mini encyclopedia of Indian politics in the post independent era. He new most of the ins and outs of political upheavals during sixties, seventies, eighties and nineties. He was a close watcher of Muslim politics and observed with disdain the discriminatory policies of the government against Muslim minorities.

With his advent in Indian politics, Syed Shahabuddin created many controversies around him. He was nominated as the general secretary of Janata party and Rajya Sabha member in 1979. Many a stalwarts in Janata party and later Janata Dal turned against him. This still didn’t deter Janab Syed Sagheer Ahmad sahib to stand like a rock in support of late Syed Shahabuddin. In 1991, Janata Dal had completely ignored Syed Shahabuddin in parliamentary election and denied him the party ticket from his favored constituency Kishanganj. Yet it was only the magnanimity, political stewardship and endless backstage efforts of Sagheer sahib that at the last moment Janata Dal had to concede and accommodate Syed Shahabuddin for a ticket from Kishanganj.

Sagheer sahab was an ardent admirer of Chandershekharji and considered him the bravest leader of his time. He was considered a close confidant of Chandershekharji, yet on occasions he would take a stand contrary to the wishes of his leader. One incident, I remember well. In 1986, when organisational elections for UP Janata Party was going on, Manager Singh an MLA from Ballia was candidate for district Presidentship. Chandershekharji somehow didn’t want Manager Singh to become the party president of his home constituency. But Sagheer Saheb openly went against the wishes of Chandershekharji and played an instrumental role in getting his friend Manager Singh elected as the Ballia Distict president.

I am personally aware of it that during his 60 years long political career, he helped many people achieve their political aims without seeking any return. I am sure nobody in the world of politics could ever claim that he accepted even a penny from anybody during his extensive political tenure. He used to travel much but he would never travel alone. He would usually stay in a middle class hotel. There were few exceptions who were fortunate enough to host Syed sahib. He would always strain his own pocket for all the expenses, not only for himself but for all those who accompanied him. He was a very caring person. If you were travelling with him, he would make sure to take care of every little thing – your ticket, your accommodation, your food and even your laundry.

Today even his political adversaries would agree with me that he was the gentlest and most honest politician of his time with an unmatched sense of self respect — something he never compromised upon.

I have no qualms in saying that India politics ill-treated its two great sons – Captain Abbas Ali khan who was a freedom fighter, a captain in Netaji’s Indian National Army and consequently got arrested and was awarded a death sentence but luckily India won independence before he could be executed.

After Independence, Captain Abbas Ali Khan spent his whole life in opposition and socialist politics. He was the president of UP Janata party when it was in power there. But all his sacrifices in the freedom movement and his contribution in the socialist movement was ignored. He was favoured only once with a single tenure of MLC. Second one is of course, Sagheer sahab. He shall be recorded as the most unfortunate and prejudiced victims of the discriminatory Indian political mindset.

In fact both Captain Abbas Ali Khan and Syed Sagheer Ahmad deserved a seat in Rajya Sabha or a provincial governorship.

Few days back he had penned down his autobiography named as “abhi ummeed baqi hai” “hope still remains” in Hindi and it was inaugurated in the Constitution Club of India. The event was joined by top socialist and intellectuals from across the country. The book received much appreciation and acknowledgement.

Today he is no more leaving behind a void which can never be filled for where can we find again this level of honesty, integrity, philanthropy and discipline. Those who know him must have plunged into deep sorrow and darkness. With Sagheer sahab a beacon of gentle light of Indian Politics has extinguished. May Allah rest his soul in peace.

____________

The author is ex-President of AMU Students Union.

source: http://www.clarionindia.net / Clarion / Home> Culture> India> Indian Muslim / by S.M. Anwar Hussain / September 28th, 2020