Lucknow, UTTAR PRADESH / NEW DELHI :

Muzaffar Ali wears many hats—filmmaker, painter, poet, fashion designer, revivalist, Sufi exponent, social worker—with consummate ease. As he prepares to release his latest labour of love, Jaanisaar, he speaks to Ambica Gulati about being in a ‘constant state of inspiration’

Filmmaker. Painter. Sufi exponent. Revivalist. Fashion designer. Music lover. Social worker. Just some of the ways Muzaffar Ali is described. But the man himself is loath to be labelled. For him, life is a singular pursuit: a quest for harmony and love as elucidated by the Sufi philosophy, “surrender of the highest order, which manifests through human compassion”.

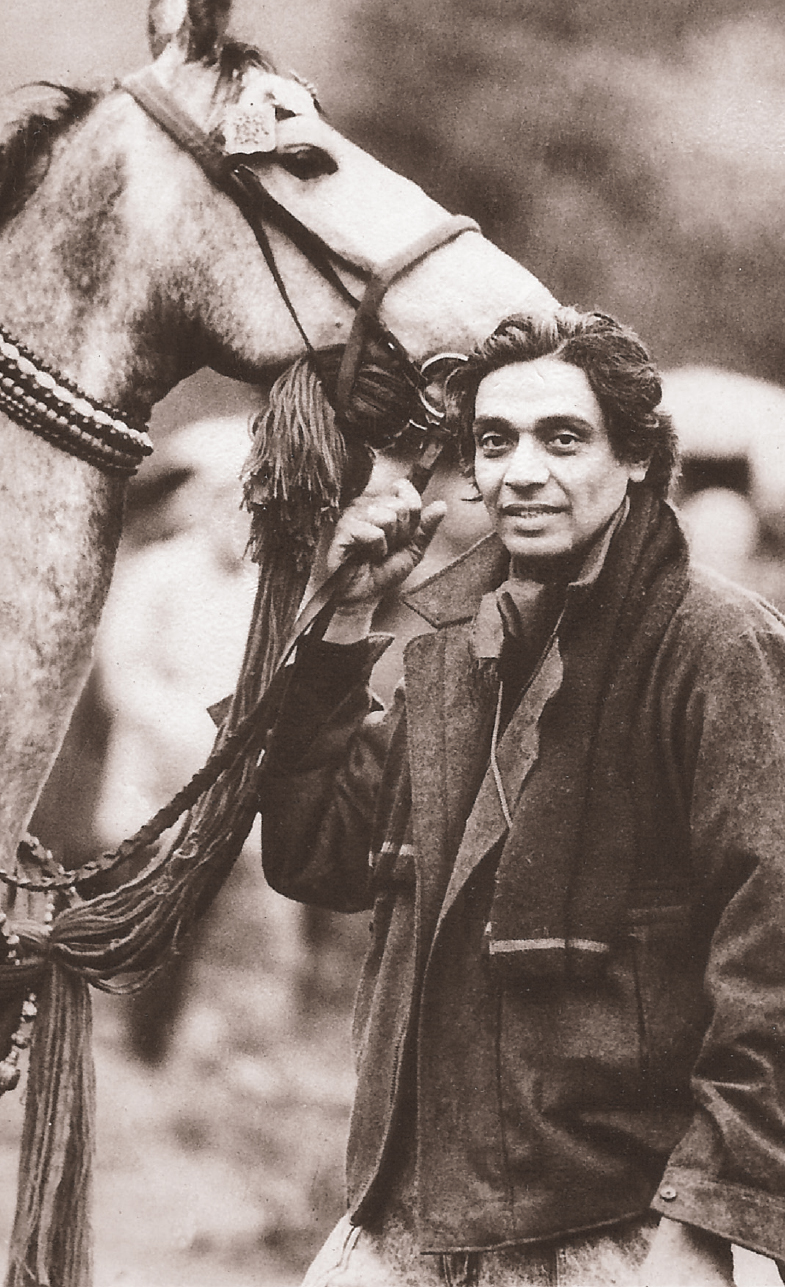

Our introduction to Ali takes place at his charming farmhouse in Gurgaon, where Barrack, his horse, runs freely in the grassy expanse while dogs laze contentedly in the morning sun. In another corner, vintage cars are parked in a shed, pregnant with stories of a royal past. Ali is the current Raja of Kotwara, a former princely state 160 km from Lucknow, but there is nothing pretentious about him or his lifestyle. Enter the farmhouse and you notice how mud, mortar and brick blend seamlessly, mirroring the owner’s constant quest for harmony and balance in keeping with the Sufi way of life. Inside the massive door, red pillars catch the eye, and once inside the glass doors, you are introduced to the sophisticated yet mellow world of a man with seemingly infinite creative nuances. Designed by his wife Meera, Ali’s farmhouse is a fusion of styles that perfectly capture the personality of the Raja—his paintings adorn the walls, old books lie open on tables, and a fireplace painted by Ali himself occupies pride of place in the centre of the room.

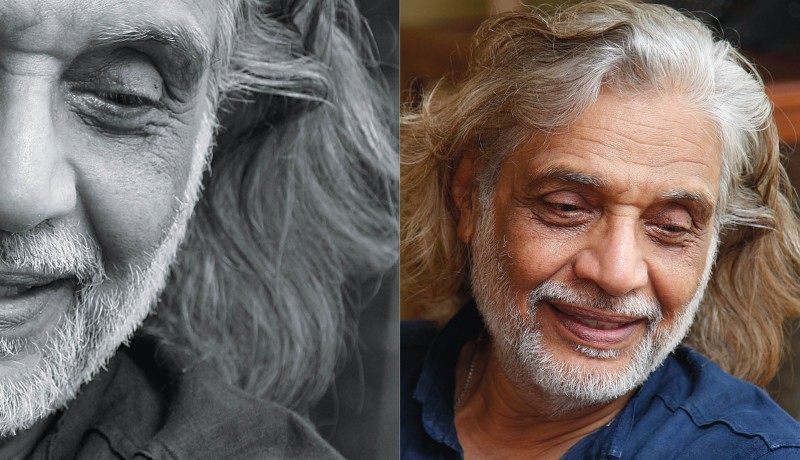

At the age of 70, white hair flowing across his elegant shoulders, Ali speaks with a quiet passion about his films, establishing the Kotwara clothing brand with Meera, spreading Sufism, creating beautiful minds, reinventing the lives of the people of Kotwara and his umbilical ties to the region. During the conversation, the Padma Shri (2005) recipient also sheds light on his soon-to-be-released film Jaanisaar, and receiving the Rajiv Gandhi National Sadbhavana Award (2014) for promoting peace and harmony.

EXCERPTS FROM AN INTERVIEW

Who really is Muzzafar Ali?

I am my parent’s child, shaped by my father Syed Sajid Husain Ali’s progressive thinking and groomed by my mother Kaneez Hyder’s cultural feathers. I grew up in an era of turmoil, when India was all for independence. Awadh had a prominent Nawabi culture. My father was the head of Kotwara, but he thought like the common man. He had studied in Scotland where he dressed up like the British, drove a sports car and was influenced by the philosophy of the Communist Party of Great Britain. He believed in an egalitarian society, and focused on health, education and work for all. In 1937, he fought his first elections against the Muslim League as he believed in a secular, democratic India. Humanism and secularism were his principles. My mother followed the purdah system. She was interested in art, culture, music and all the influences you see in Umrao Jaan.

What is common to Muzzafar Ali the filmmaker, social worker, painter, Raja and fashion designer?

An artist in quest for a balance between humanity and beauty.

Were you groomed for the arts at home? And was the pursuit of creativity a deliberate career choice?

I was studying science at Aligarh Muslim University. My father believed in the Nehruvian vision, which was progress through science and technology. He wanted me to be a part of that. After the zamindari system was abolished in 1957, he locked himself up and studied law. During India’s transition, he also transformed. He gave up wearing mill-made clothes and opted for khadi. Suddenly, there was a perceptible shift from a lavish lifestyle to a Spartan one. I guess something similar happened to me in university. I discovered poetry and poets like Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Rahi Masoom Raza, and my education became an art of science or perhaps it was the science of art that got to me. I read the works of Rumi and became passionate about the Sufi way of love and surrender.

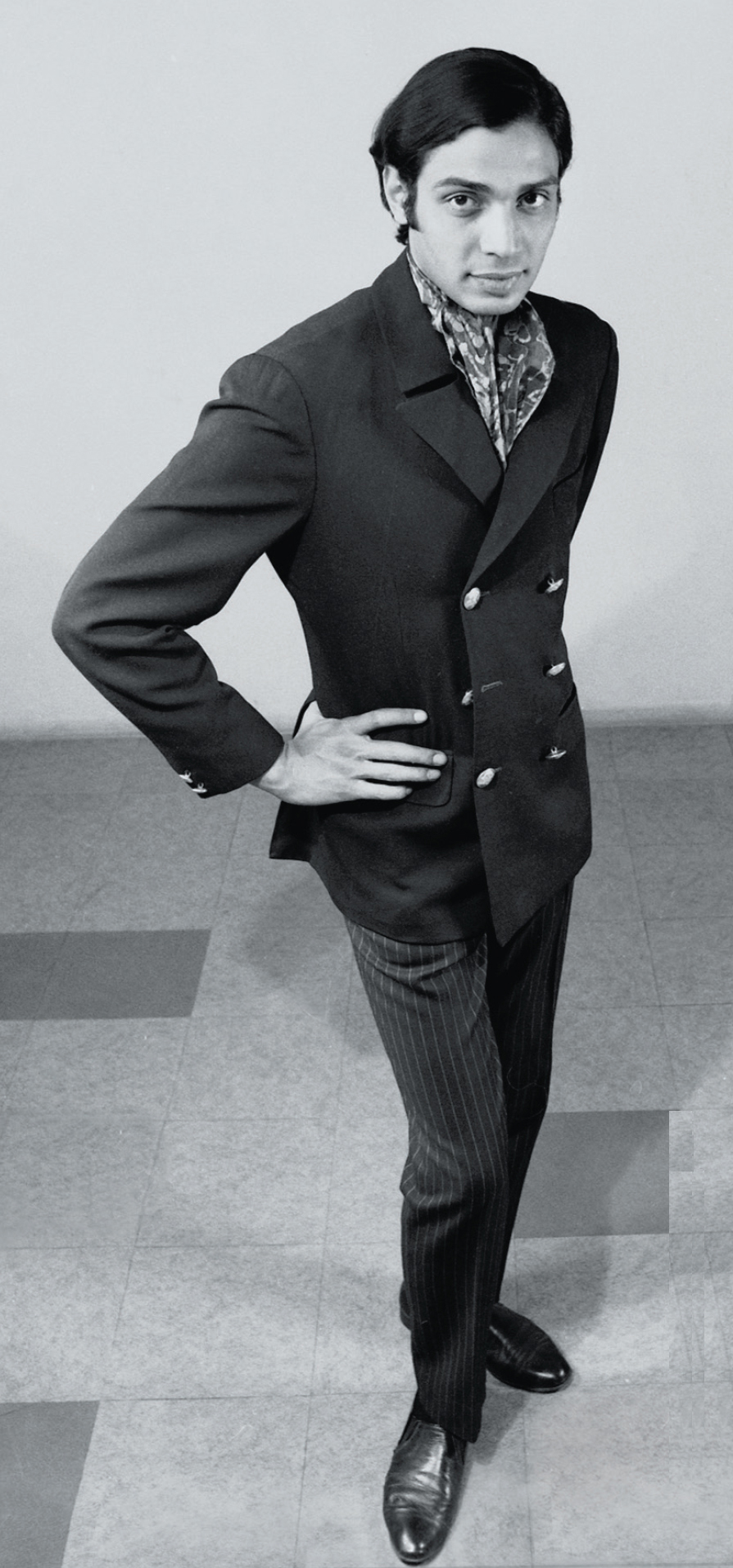

I completed my BSc but went to Kolkata to work in an advertising agency headed by renowned filmmaker Satyajit Ray. His thoughts and style were a strong influence on me. I realised that film was an interesting medium to express your beliefs. But my introduction to the arts was through painting. I loved to sketch and paint since childhood. I even won many prizes in school.

Do you still paint?

I still paint as much as I can create time for it. I like to live with my paintings, in constant dialogue with them. Therefore, I am in a constant state of inspiration. These works are in my own homes, mostly in the Gurgaon home. I have had 10 one-man shows; I would like to show soon if I meet the correct person through whom I should hold an exhibition.

Did you have any doubts when you chose a career different from the one you were being prepared for?

Nothing is impossible and I was brought up in an open-minded atmosphere. I had seen my father take a quantum leap from being a zamindar to giving people a voice and wearing hand-woven clothes. He did not believe in a capitalist society and always said ‘a penny saved is a penny earned’. My salary in Kolkata was ₹ 300 and my hostel fee was ₹ 150 per month. But I managed.

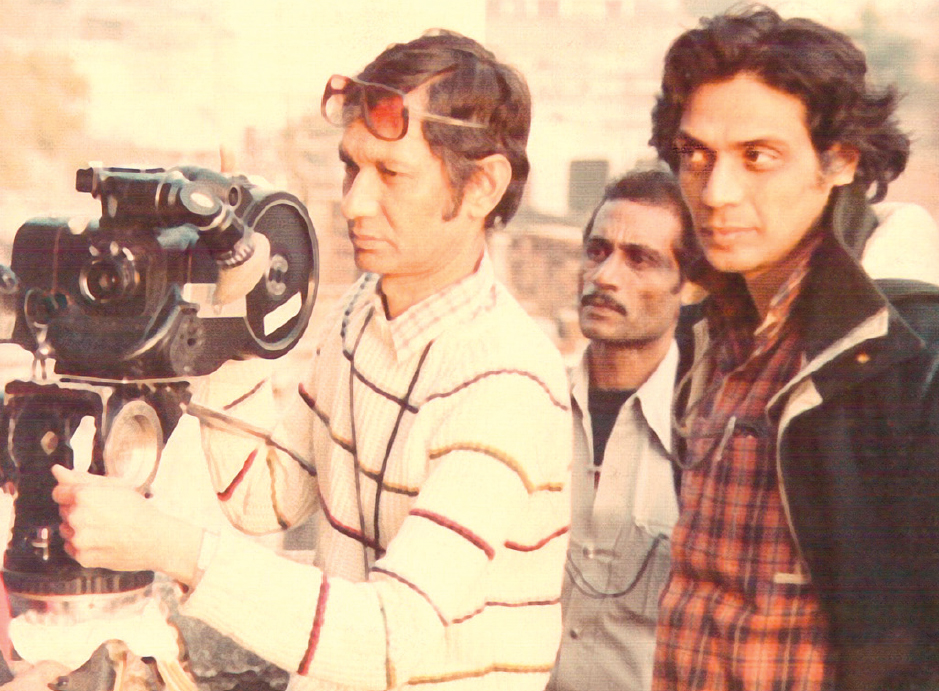

How did films happen?

The first film I made was Gaman. Working with Satyajit Ray, I had realised what a camera could do. So my journey was from sketching to moving images. It’s a journey I continue to repeat every time I make a film. Each film, therefore, became a milestone in my understanding and expression of life and has been rooted in the soil of Awadh, Lucknow and Kotwara. They have been shot there, with natives featuring in them.

I had started working with Air India in the communications department in the 1970s. I worked there for 11 years. I lived in Mumbai and I would see people coming from villages to the city. They would lose their identity to earn a living. This was the theme of my film Gaman. Social issues and cultural ethos always influenced me. In 1976, I started Umrao Jaan. The film captured the culture of Awadh and times of Wajid Ali Shah. All the detailing in the movie was what I had seen and learnt at home. All the poetry and love and surrender I was in love with found its way into the songs. In Anjuman, I explored the lives of chikan workers and the exploitation of women.

What about your famed film Zooni, which is yet to see the light of day?

Zooni was based on the folklore surrounding 16th century Kashmiri poetess Habba Khatoon. It was my way of expressing pride in the beautiful state of Kashmir, my way of showing that violence will lead us nowhere. Zooni is a big exploration into the people and culture of the Valley and something that neither I nor the people are ready to undertake because of what has happened since 1989. It is an unfinished dream and if I meet the right people, it may become a reality. The script will need to be revisited to suit the audience of today but the spirit is universal and, therefore, it has to be a global film.

What can we expect in Jaanisaar? Is it a sequel to Umrao Jaan?

This film is centred on the siege of Awadh, the revolt of 1857, and romance between an Anglicised Raja and a courtesan. It stars newcomers Imran Abbas Naqvi and Pernia Qureshi. It is not a sequel to Umrao Jaan but takes off from where Umrao Jaan ends in the same region. This is my fifth feature film. Not counting Zooni, I have done several serials and short films on Sufism.

Umrao Jaan established Rekha as one of the most beautiful women in the country. It also had classical songs such as Dil cheez kya hai…. Will Jaanisaar offer something similar?

The focus is on the culture of Awadh. The rest is up to the audience, to see where it goes.

What will be your next artistic endeavour after Jaanisaar?

Plans after Jaanisaar will become reality only after the film is released and accepted. I think big but take small, measured steps. Every film is a dialogue with my audience.

The creation of the Kotwara brand—how did that happen?

Ambience is very important for me. Kotwara is a beautiful 14-acre, green land with mango groves. In films, my actors always look beautiful, so I thought why not clothes in real life? Kotwara has been my studio for all my creative shades. It was where I began painting and it is where my work with the revival of chikan began. It also houses a school for children and Jaanisaar is also being shot there.

Fashion happened during the making of Zooni in 1988. American fashion designer Mary McFadden visited us back then and after seeing Kotwara, she said it could be a haven for crafts. Fashion was still evolving in those days and even known names like Suneet Verma worked with Mary. In 1991, my father passed away and I was wondering what to do next with his huge legacy. Meera supported me and helped turn Kotwara into an asset. Sugarcane farming was the mainstay of the region but there was never enough. We decided to revive the crafts and got a few people from Lucknow to train a few willing workers. We looked at how to make new motifs suited to the changing world and new works with zardozi. And ‘Dwar Pe Rozi’ [a charitable society] was born. Now, there are 300-400 people working on this in different pockets. Then, we built a small school for children; there are 300 children studying there.

How did the brand hit the limelight?

We started participating in fashion weeks in 2000, and the rest is history.

What do you feel is the biggest contribution to your hometown through the Kotwara brand?

Kotwara is a concept, an idea. Inspired by my first film Gaman, it aims to provide employment at one’s doorstep under the Dwar Pe Rozi vision. In Kotwara, I have tried to pour in my creative skills with human resources from the village to create craft and couture in which my films could add value. I think it is a very slow process and is succeeding because of the thought and style that is going into it, from both Meera and I.

How did Jahan-e-Khusrau, the annual Sufi festival you have been organising at Humayun’s tomb in Delhi, happen?

The Sufi way of love and surrender has always been my approach to peace and harmony. The soul’s call is to create a union. The music albums I have brought out are centred on this Sufi spirit. Paigham-e-Mohabbat had lyrics by some of the most distinguished poets such as Rahi Masoom Raza, Ali Sardar Jaffery, Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Ahmad Faraz, Qazi Nazrul Islam and Jan Nisar Akhtar. Other albums are Jahan-e-Khusrau, a tribute to Hazrat Amir Khusrau, while Raqs-e-Bismil (Dance of the Wounded) is a collection of ghazal inspired by Rumi. I received the support of then Delhi chief minister Sheila Dixit for the festival. Delhi is the land of Sufi saints and has the dargah of 36 saints. This festival was a natural way of felicitating the Sufi spirit of union. We started in 2000. Given the chance, I would also like to organise a Wajid Ali Shah festival in Lucknow. In 2005, I also started the Rumi Foundation and published two motivational journals and poetry.

Are you also translating Sufi works? And how can Sufi music bring peace to the subcontinent?

For me, Sufi poetry is the final stage of love and surrender. Every time I use it in an album or in Jahan-e-Khusrau, I try to translate it. Although I am not very good at translation, I don’t want listeners to miss out on the meaning. Raqs-e-Bismil with Abida Parveen, selected, composed and translated by me, is one such effort.

Life’s journey has brought you to the Rajiv Gandhi National Sadbhavana Award. How does this make you feel?

I sometimes wonder if I even belong there. I have been graced along with a galaxy of people such as famous scientist Yashpal and Mother Teresa. The award is a significant recognition in our country. In a nation of such vast ethnic diversity, taking the route of religion to unite people can lead to unprecedented intolerance. We need to celebrate those who have upheld these human values. The award leaves you with the responsibility of living up to these ideals.

Have you ever felt that you may not be able to live up to the expectations of the people around you?

I feel I could do more for the school. But I focus on creating more beautiful minds and let the doubts out.

How did you meet Meera? Does the age difference ever make you feel insecure?

I met Meera in Delhi when I was uprooted from Kashmir with an incomplete film. I found her an extremely powerful anchor in my life. I was making an hour-long film on the life of Hazrat Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti of Ajmer, called Seena Ba Seena (From the Heart to the Heart). I gave her a small role and we married soon after that. That was 25 years ago. Age did not matter then, nor does it now. She is honest and dedicated. She thinks out of the box, is a talented architect, and open and receptive to new things and ideas.

Are your children also involved in creative pursuits?

My eldest son Murad [from his first marriage] is based in Delhi and is an actor; Shaad [from his second marriage] lives in Mumbai and is directing films; and my daughter Sana [with Meera] has started helping us with the clothing brand. But now I look at the whole world as a child. I do not think about my biological children only, but in a broader scope of creating happier worlds.

What is a typical day like for you?

Walk with my dogs. Playing with my horse. Work on my thoughts. Sharpen my aesthetics through poetry and music. Sketch and paint.

Has age made any difference to your life and work? Has it mellowed you or contributed to your growth?

By His grace, I have learnt to become sharper with age, and I believe this is the time to enlighten the youth with dreams to improve the world in which we live. Create open and questioning minds.

What is your future vision?

To create beautiful, open minds. I find pleasure in seeing the children in school. They are going to be the new harvest. In turn, they will create a happier world for others. I will keep sharing whatever I can, in my own way.

Photos: Avinash Pasricha Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine January 2015

source: http://www.harmonyindia.org / Harmony India.org / Harmony – Celebrate Age Magazine / January 2015