Palani / Trichy, TAMIL NADU :

S.M. Munawwar Nainar learnt the language at Cairo University (1955-59) and did his M.A. and Ph.D at Delhi University and JNU respectively. His command of the language led him to serve as the Indian government’s official interpreter in the 1970s. He recalls the most memorable meetings of Indian and Arab leaders at which he was the interpreter.

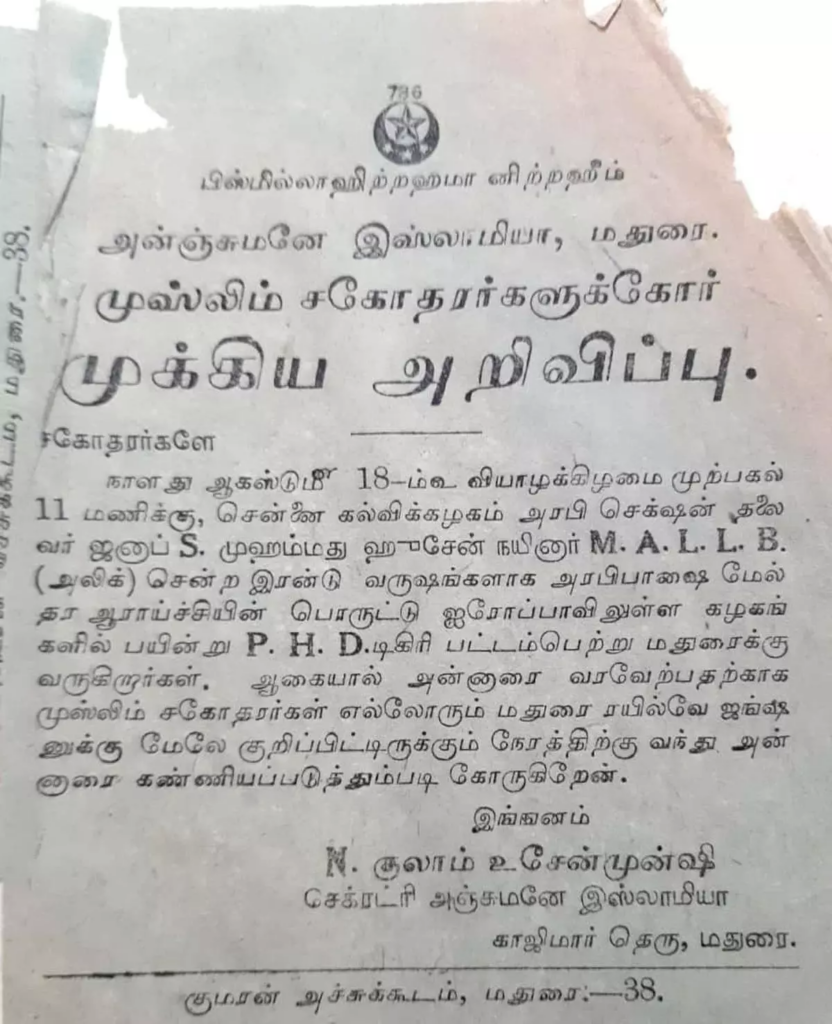

S. M. Munawwar Nainar (second left, standing) with Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein in Baghdad in 1975. The meeting helped to cement the bilateral ties. | Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

My journey with Arabic began in the 1950s, when my father, Syed Mohamed Husain Nainar, professor and head of the Arabic, Urdu and Persian Department at the University of Madras (1927-1954), wished at least one of his sons to study Arabic in depth. I was drafted to the cause, though my general academic performance was middling. Eventually, I did four years of immersive language training in Arabic at Cairo University (1955-59), where I got my B.A. ‘Licence’ (degree) with a ‘Jayyid’ (good) grade. I followed it up with M.A. Arabic at Delhi University, and a Ph.D (on Arabic loan words in Hindi, Urdu, and Tamil) at Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi.

Arabic has led me to many interesting destinations, from diplomatic service and teaching to radio broadcasting and literary translation. But, to me, the most memorable of these are the occasions when I served as the Indian government’s official interpreter in the 1970s. I had been appointed as one of the Arabic teachers at JNU’s School of Languages at the time. The interpreter’s assignment was an honorary posting, and I was recommended for the job by our Vice-Chancellor G. Parthasarathy, based on my previous experience as the press secretary at the Indian Embassy in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (1969-72).

A visit to remember

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s state visit to Iraq from January 18 to 21, 1975, was a much-covered event, because of the charisma that the Indian and Iraqi leaders projected in public. It is also considered a visit that cemented friendly ties between the two countries.

Saddam Hussein was at the Baghdad airport to receive her and the Indian delegation. He invited Mrs. Gandhi to the waiting limousine and boarded it after her. I was seated behind them. As we were proceeding, he asked the driver to slow down near a mosque and said, “This is where we had a crucial meeting of our Ba’ath Party after which I took over the reins of power.”

Official parleys were held the next day, after which Mrs. Gandhi wanted to have a private discussion with the Iraqi leader. When she asked him whether he wanted his interpreter to be present too, he declined. Pointing to me, he said, “Your translator is enough”.

We were received by Saddam seated on a chair with a hard wooden backrest (to deal with a spinal problem, he explained). As the two leaders spoke for about an hour, the Iraqi strongman’s trademark stern demeanour relaxed. (Earlier, on March 25, 1974, Hussein was on an official visit to India, where he was received by the then Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi.)

Rousing reception at Baghdad University

The Indian Prime Minister received a rousing reception at Baghdad University on January 20, where around 5,000 students had assembled in the large auditorium. The programme began with a welcome address in Arabic by the Vice-Chancellor, which I translated simultaneously to the Prime Minister in a low voice as I was seated behind her.

Mrs. Gandhi spoke extempore for about 15 minutes, during which there was pin-drop silence. I scribbled down notes. My translated version drew a big cheer from the audience that lasted for five minutes, a testimony to her popularity. The function also included the conferring of an honorary law degree on Mrs. Gandhi. However, as the students swarmed around the leaders after the event, I got lost in the melee. The security officers quickly conducted Mrs. Gandhi to the official motorcade; but when she noticed I was missing, she sent them back to find me. “Kahaan reh gaye aap? [Where were you?],” she asked me as I joined her in her car. To me, Mrs. Gandhi’s concern for her team members, irrespective of their rank, was one of her most admirable traits.

The 1970s were an important period for West Asia, where countries of the Persian/Arabian Gulf were declaring their independence from British rule. In 1971, the former ‘Trucial States’ — Abu Dhabi, Ajman, Dubai, Fujairah, Ras Al Khaimah, Sharjah, and Umm Al Quwain — decided to form the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Their neighbours — Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, and Oman — also became independent that year. As India was keen on evolving a rapport with these oil-rich countries, many official visits were made to and from the Gulf countries.

A dragging flight

I was part of the delegation accompanying former Minister for External Affairs Sardar Swaran Singh on a tour of Oman, Abu Dhabi, Dubai, and Qatar in the mid 1972. We boarded a Fokker Friendship plane in Delhi and, after about four hours, landed at the Jamnagar Air Force Station for re-fuelling. Then we resumed our journey towards Muscat, our first port of call, which we reached after seven hours of flying. “It was like walking from Jamnagar to Muscat,” Sardar Sahib said jokingly.

In Oman, Sultan Qaboos bin Said had recently deposed his father Sultan Said bin Taimur. The luncheon banquet was sumptuous: stuffed lambs and rice, followed by Omani halwa, carried on large platters by six persons (three on each side).

In the Qatari capital Doha, Emir Sheikh Khalifa bin Hamad al-Thani spread out a huge blueprint and explained his nation’s development plans. Years later, when I worked in Qatar’s Education Ministry from 1983 until the 2000s, I saw that most of them had been implemented. Early Gulf leaders, in keeping with their nomadic Bedouin culture, would avoid venturing into the harsh sunlight. Thus, it happened that we had to meet Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan al-Nahyan, the first President of the UAE and the ruler of Abu Dhabi, at midnight. Dubai already had started its course towards developing the tourism and hospitality sectors. I was in my thirties during these official engagements; today I am 87.

In 1975, when I was part of President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed’s visit to Egypt and Sudan, I had an opportunity to mention to Egyptian President Anwar el-Sadat that I had graduated from Cairo University. He was pleasantly surprised and wished me well. Arabic brought a boy from Palani to the corridors of power for a while and left behind a cornucopia of memories.

(The author had also served as the official interpreter for the Indian government during other high-level meetings with leaders from Middle East and North Africa countries. He is based in Tiruchi.)

source: http://www.frontline.thehindu.com / Frontline / Home> News> India> Tamil Nadu / by S M Munawwar Nainar / December 08th, 2023