Yangon (Rangoon), MYANMAR (formerly BURMA):

Close to the Shwedagon Pagoda in Myanmar, this dargah is the last tribute to the Mughal ruler and poet.

Photos: Subhadip Mukherjee

Myanmar (Burma) has some uncanny ties with India when it comes to the freedom struggle. Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose was imprisoned in Mandalay and the last Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar, who was also imprisoned, later died in Yangon (Rangoon).

If one visits Yangon, then one must visit the Dargah of Bahadur Shah Zafar. It is an irony of sorts when one thinks of the last Mughal emperor not being able to spend the last days of his life in a country where his ancestors once ruled. For the British, Bahadur Shah Zafar was more like a threat; they were constantly worried that he could be used as a proxy leader for another attempt at a revolt in India.

After being arrested from Humayun’s Tomb during the Sepoy Mutiny on September 19, 1857, he was spared the death sentence and negotiated a life in exile instead. They thought it was better to have him sent to exile in Myanmar, and considering his health, they were almost certain that he would never set foot in India again. Bahadur Shah Zafar left Delhi along with his wife, two sons, and some close support staff on October 7, 1858.

More than a rebellious ruler, Bahadur Shah was more into poetry and that’s exactly how he spent the sunset years of his life in Myanmar. The British were paranoid and even prevented him from getting supplies of pen and paper fearing that he would pass messages to his supporters back in India.

Life in Yangon

He lived in a small wooden house that was located very near Shwedagon Pagoda. If you are visiting Yangon, then you’ll find Shwedagon Pagoda as one of the major landmarks in the city. His life was miserable out here with a very limited supply of food and without any pen and paper. So, as a last-ditch attempt, he started using charcoal and scribbled poetry on the wall of his home.

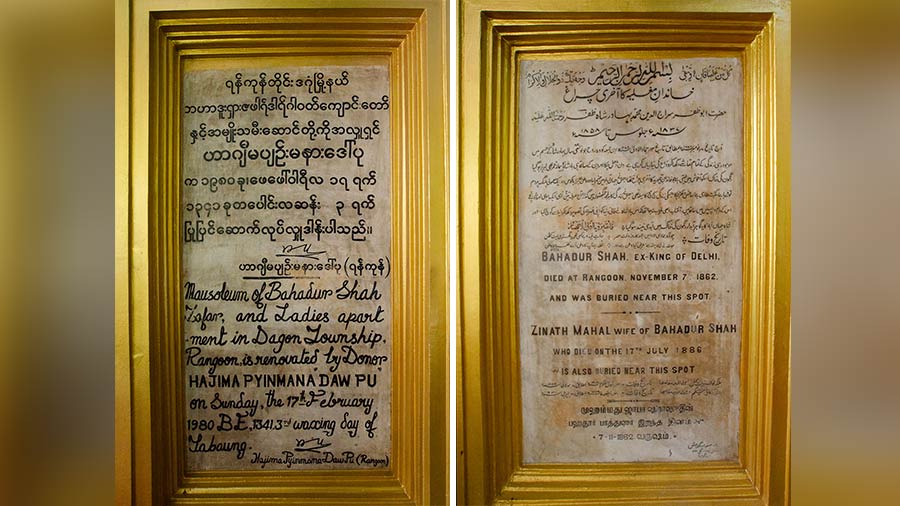

His life came to an end at the age of 87 on November 7, 1862. By then, he was completely bedridden and unable to eat or drink. A very unfortunate end to the last Mughal emperor of India.

Even after his death, the British were paranoid and hurriedly buried him without giving him the last respect that he deserved as the last emperor. Just a small plaque was placed on top of the grave and the rest was kept as simple as possible. This was purposely done to prevent his followers from making this place into a pilgrimage spot.

Four years later, his wife also passed away in Yangon and was buried right next to him.

The Lost Grave

With time, people simply forgot about this grave just exactly as the British wanted. To make matters more complicated no official records were kept as to the exact place where he was buried.

The discovery of the grave happened by chance in the year 1991 during an expansion work of a prayer hall that was being carried out by labourers. Two graves were found with small inscriptions on top of them. While one had the name Bahadur Shah Zafar, the one next to it was that of his wife Zinat Mahal.

Further excavation was carried out on the two graves and upon opening up the grave of Bahadur Shah Zafar, the skeletal remains were found wrapped in a silk shroud.

After this discovery and realising the importance of the grave, it was decided to restore and renovate the graves and the surrounding area. With support from the local community, the local government, and further support from the Government of India, a permanent structure was constructed over these two graves. A dargah was constructed at this very spot making it fit for the last Mughal emperor.

Dargah of Bahadur Shah Zafar

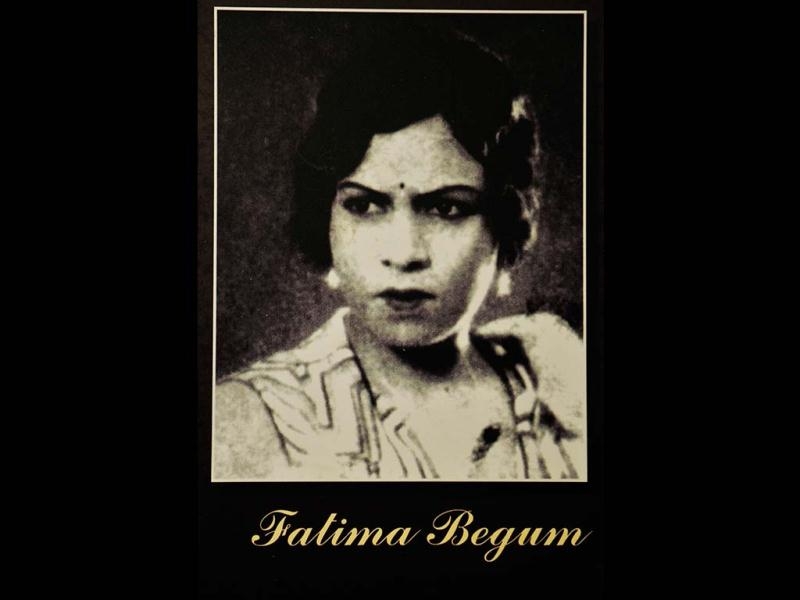

The dargah has two levels, the top level has a large prayer hall and a room with three decorated tombs. These tombs are that of Bahadur Shah Zafar, Zinat Mahal, and his granddaughter Raunaq Zamani. The surrounding walls in this room have only three known photographs of the emperor and poetry written by him lamenting his life in exile.

Kitnaa hai badnaseeb ‘Zafar’ dafn ke liye do gaz zamin bhi na mili kuu-e-yaar mein

Bahadur Shah Zafar

There is however another secret to this place. There is a room located in the basement of the dargah. This is the room where the original grave of Bahadur Shah Zafar was located when it was discovered. The grave now has been converted into a decorated tomb. This is the very place where the last Mughal emperor was buried and was thought would be forgotten. But as luck would have it, it is now somewhat fit for an emperor. It’s sad that Bahadur Shah Zafar could never return to the country he once ruled. He remained in exile even after he died in Myanmar.

The Kolkata Connection

Bahadur Shah Zafar along with his wife Zinat Mahal were also accompanied by their two sons Jawan Bakht and Jamshed Bakht. His sons never left Burma and settled there and ultimately died there only. Jamshed Bakht had two sons. One of his sons, Mirza Bedar Bakht, came back to India and settled in Kolkata. He married Sultana Begum with whom he had five daughters. Mirza Bedar Bakht had a very quiet life living in a slum and earning by sharpening knives and scissors. He died in the year 1980 in this very city and was buried here in Kolkata.

Working for more than a decade in the book retail and publishing industry, Subhadip Mukherjee is an IT professional who is into blogging for over 15 years. He is also a globetrotter, heritage lover and a photography enthusiast.

source: http://www.telegraphindia.com / The Telegraph Online / Home> My Kolkata> Historical Landmark / by Subhadip Mukherjee / April 03rd, 2023