Hyderabad, TELANGANA :

The pages of this Sanskrit trestise eschew a story of timeless love, passion and the strife it accompanies

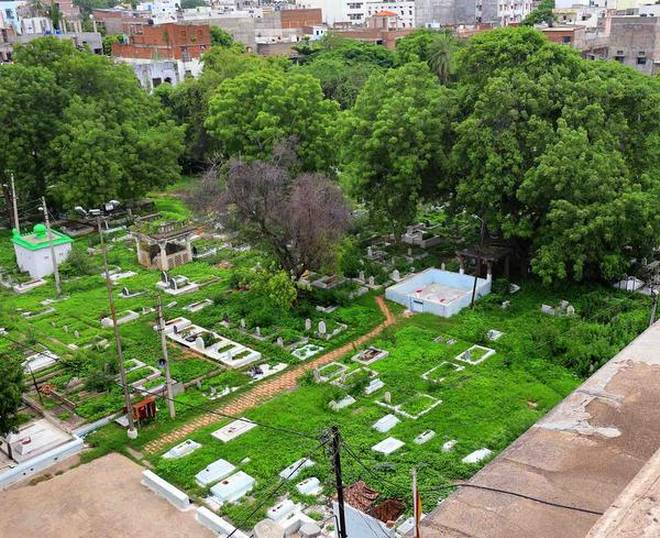

Misrigunj is one of the old city areas of Hyderabad where it is easy to get lost as the lanes and bylanes double back and are in no particular order. Even a compass will be of little use, forget about online maps. In one of the lanes that lead on from one of the biggest domes in the city is the grave of Syed Kalimullah Hussaini or, as he was known in his lifetime, Akbar Shah. Walking in the lanes and standing near his grave in Misrigunj, it is difficult to imagine that the young man wrote a Sanskrit treatise on love, heroines and their moods called Sringaramanjari. The treatise on the many moods of love begins with a Guru stuti.

Guru Ganapati Durga Vatukam Shivamachutam

Brahmanam Girijam Lakshmim Vanim Vande Vibhoteye

If Akbar Shah wrote the Sringaramanjari, credit has to be given to Sanskrit scholar Venkataraman Raghavan for resurrecting the book based on two manuscripts and giving insights into the life of Akbar Shah or Bada Akbar. Raghavan became curious in 1943 when he saw a Sanskrit manuscript in Government Oriental Library, Mysore. Using other material from Tanjore Library, Raghavan published a book with an exhaustive introduction leading to the adaptation of the work for Bharatanatyam and Carnatic music.

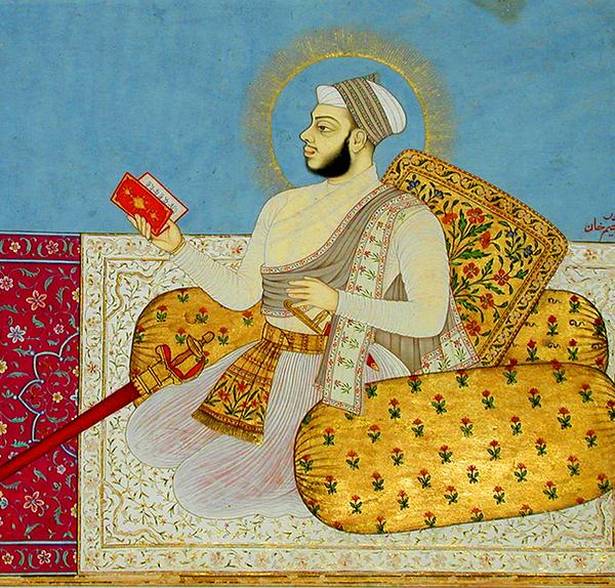

To understand how a book on love written in Sanskrit by a Muslim scholar living in a Sufi khankah came to be written about in the latter half of seventeenth-century Hyderabad would be a challenge. Akbar Shah was the son of Shah Raju Qattal who traced his lineage back to Gesu Daraz credited with bringing Sufism to Deccan. Akbar Shah grew up in his father’s khankah along with another young boy: Abul Hasan, or as Shah Raju called him Tana Shah(young king).

The lines of religion and language in Deccan were like lines drawn in the sand. It was in Deccan that a king moved his capital from Gulbarga down south to Bidar where the linguistic boundaries of Kannada, Telugu and Marathi met. The language and court practices were a blend of the Persian world and those from the native kingdoms. The taj worn by kings became the colourful pugree in course of time.

It is in this flexible world that a Muslim scholar could sit inside a Sufi khankahat the feet of his father and write a work that dwelt at length about the fickleness of love, heroines, beauty and attraction. If the love of your life is angry, Sringaramanjari has a recipe to solve the problem. It suggests a time and a place with a romantic mood like spring and moonlight. It also gives six ways to win over the love: pleading, gift, winning over her friends, indifference, falling at her feet or changing the circumstances.

One of the topics that Akbar Shah ponders is whether a courtesan is capable of real love and after much deliberation concludes that she has love for one person but feigns love with many so that she can carry on her life.

Unfortunately, Akbar Shah died young. Raghavan uses evidence in the book as well as a firman issued by Aurangzeb to prove that he died before 1675. Much before his playmate, Abul Hasan could rise to the pinnacle of giving one final burst of cultural efflorescence.

The mazar (grave) of Akbar Shah is in a much better shape now than it was in 1949.“People still come here and spread flowers,” says the mutawalli of the dargah of Shah Raju Qattal.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Society> History & Culture / by Serish Nanisetti / September 03rd, 2018