NEW DELHI :

Mujibur Rehman overlooks pivotal reasons jeopardising the political future of Muslims

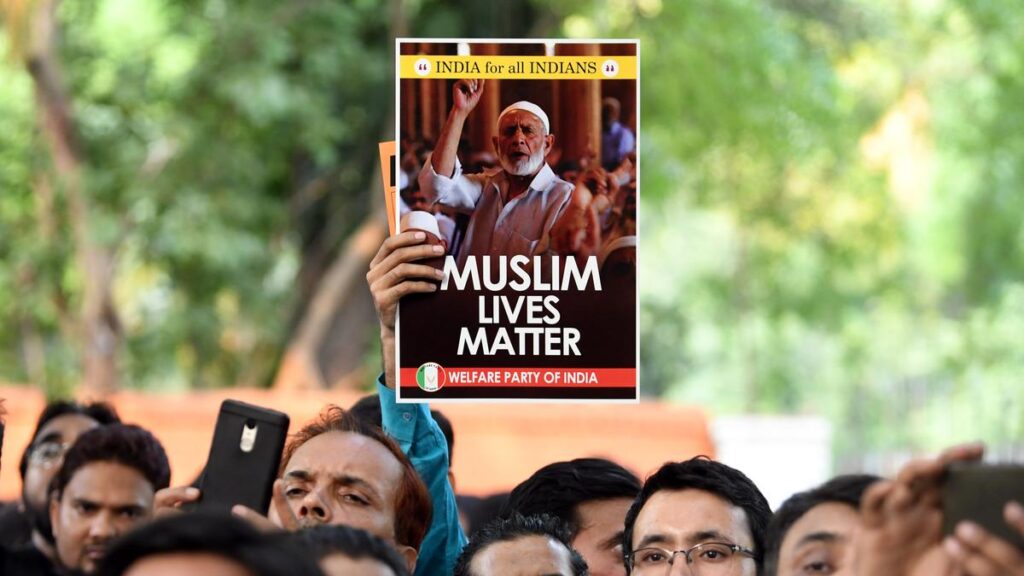

At a protest against mob lynching, in New Delhi. | Photo Credit: Sandeep Saxena

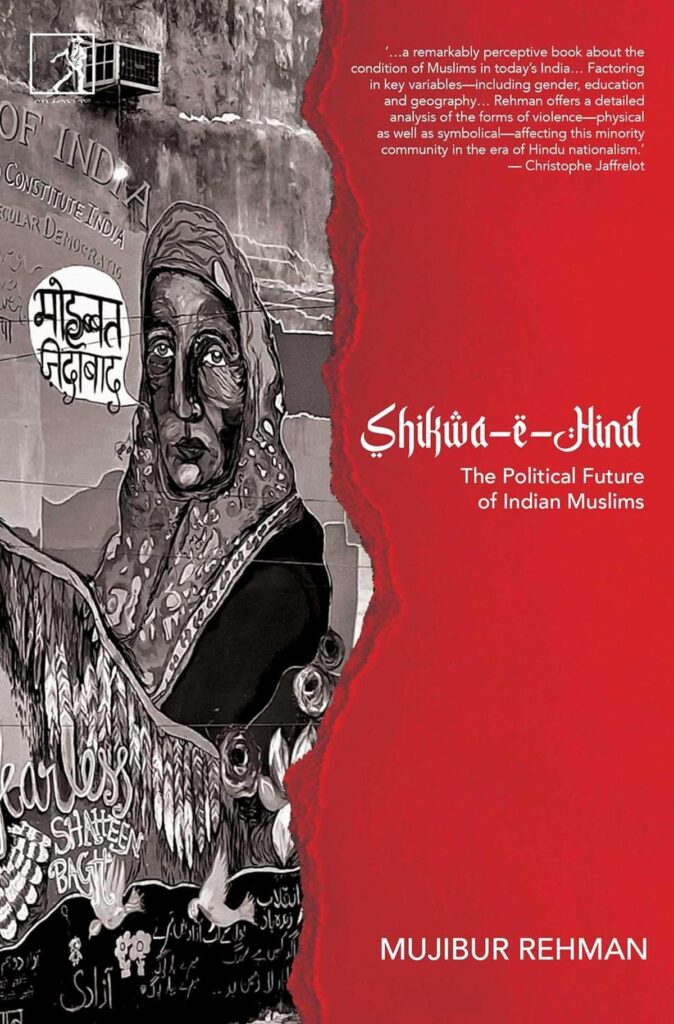

Mujibur Rehman’s Shikwa-e-Hind: The Political Future of Indian Muslims takes its title from the poem Shikwa (The Complaint) composed in 1909 by the great philosopher-poet Muhammad Iqbal (1877-1938).

If Shikwa was an aggrieved remonstrance by faithful Muslims (shikwa-e-arbaab-e-wafa) against god for having forsaken them despite their fervent loyalty, Shikwa-e-Hind is a complaint against majoritarian India for plotting “to de-Islamise” the country through its “multipronged attack on everything associated with Muslims.”

But the book is marred by the huge amassment of superfluous information on the historical “why and how” of Muslim political exclusion. Had the author realised that the Muslim past — especially what they went through before, during, and immediately after Partition — is a fait accompli, his book would not have suffered from a lack of focus on what Muslims must do to ameliorate their present situation.

Simplistic approach

Members of Muslim organisations in Bengaluru call for government action against attack on Muslims in BJP-ruled States across India. | Photo Credit: K. Murali Kumar

Muslims have been demonised, abused, suspected of various kinds of jihad, and even lynched in some parts of north India prompting the Supreme Court, in 2018, to suggest that Parliament must enact an anti-lynching law against cow vigilantism and lynch mobs.

The Hindu Right has hinted that it doesn’t want the political empowerment of Muslims as it would lead to the establishment of the shariah. In April 2022, priest Yati Narsinghanand reportedly asked Hindus to have more children to prevent India from becoming an Islamic country. He warned that in 20 years 50% of Hindus “will convert” if a Muslim became India’s prime minister.

A gathering of Muslims at Thennur, Tiruchi district, wear masks of Gandhi, Ambedkar, Periyar and other freedom fighters, to oppose the Citizenship (Amendment) Act. | Photo Credit: M. Moorthy

Shikwa-e-Hind says very little about how Muslims must respond to such unfounded accusations. The few remedies it prescribes are simplistic, platitudinous, and one-sided.

If, for instance, the future of South Indian Muslims “hinges on the ability of a new political class to preserve the rich legacy of Periyar”, for all other Muslims it depends on their ability to “explore a possibility with fellow secular citizens of other faiths” to establish “a secular polity with rights for minorities.”

The book ends with the banal peroration that India must restore its democratic habits because the political future of Muslims “directly depends on the future of Indian democracy.”

Besides, Shikwa-e-Hind contains this astonishing statement in the concluding chapter:

“For Indian Muslims, the options are very limited. As a religious minority, it no longer has a choice to ask for a separate nation — an option it has exhausted with catastrophic consequences with the creation of Pakistan and later Bangladesh.” (p.348)

Is the author suggesting that if the option had not been exhausted, Muslims would have had the choice to demand a separate nation?

Religion over politics

Although Shikwa-e-Hind blames Muslims’ excessive interest in religion (deen) on “Maulanas and various Jammats” it has no shikwa against clerics or religious bodies whose consuming passion for sectarian legalism unwittingly justifies the fears of the Hindu Right and thus, jeopardises the political future of Muslims.

Thousands of Muslim women on the premises of Lucknow’s Teele Wali Masjid to protest against the triple talaq bill, in 2018. | Photo Credit: Rajeev Bhatt

For instance, the All India Muslim Personal Law Board (AIMPLB) declared that the recent Supreme Court ruling on the maintenance of divorced Muslim women (under Section 125 of the CrPC) was “against the Islamic law (Shariah)”, and vowed to overturn it legally.

Yet, Shikwa-e-Hind would have us believe that “the Board has been committed to the role and rights of women.” The book laments that despite the AIMPLB “becoming more and more sensitive towards the role of women”, it is “still seen as a patriarchal body.”

In a video that negates this assessment, AIMPLB member Maulana Sajjad Nomani told the new Bangladeshi regime that Afghanistan (ruled by the anti-women Taliban) is “the latest example” of a “successful welfare state”, therefore, “please don’t hesitate to take the benefit of the experience of Afghanistan.”

In July this year, West Bengal Minister and Kolkata Mayor Firhad Hakim said that those not born in Islam were “unfortunate”, and therefore, “we have to bring them under the fold of Islam. Allah will be happy if we do so.”

In Muttahida Qawmiyyat aur Islam (1938), Hussain Ahmad Madani, who promoted “composite nationalism” against Jinnah’s two-nation theory, had already expressed the hope that the need for liberation from the miseries of the British would no longer remain if all Indians (tamaam baashindagaan-e-mulk) entered the sphere of Islam (halqa-e-Islam mein daakhil hojaayen).

Amid all this, several Muslim schools in India (mostly run by the financial elite) have been indirectly keeping out non-Muslims by making skullcaps and hijab a mandatory part of the uniform. Even Muslim students who come without wearing these identity markers are not allowed to enter their classrooms.

In the context of the hijab controversy, Shikwa-e-Hind cites several experts to rightly argue that if the choice for Muslim girls to wear hijab was curtailed then it would stand in the way of their education. However, the book does not hurl this argument against Muslim schools that deny students the choice to discard the hijab or skullcaps. It would appear that Muslims go to court only when hijab bans affect their education, not when the imposition of hijab affects it.

Children at a Muslim school. | Photo Credit: Getty Images/istock

Maulana Azad’s advice

Some of the foregoing events may have happened after the publication of Shikwa-e-Hind. But the religious supremacism that defines them is not new. Yet it merits no discussion in the book which, however, complains about Muslims’ lack of interest in politics without pointing out that most Muslim leaders including Maulana Azad advised the community against having its own political identity.

Maulana Azad (right) with Mahatma Gandhi | Photo Credit: The Hindu archives

In 1948 Azad said: “If in the Indian Union there is a single Muslim or group of Muslims who think that Muslims should have a separate political organisation it would be better for them to go to Pakistan.” Azad had earlier warned that after Partition Indian Muslims “will be left to the mercies to what would become an unadulterated Hindu raj.”

This shows that the political isolation of Indian Muslims is to a large extent self-imposed, and a result of their inability to challenge their politico-religious leadership. They appear to be more interested in their religious rights than secular politics.

Their future, therefore, depends not only on the democratic defeat of Islamophobic forces, but also on the intellectual vanquishment of Muslim religious leaders who play politics, and Muslim politicians who dabble in religion, to maintain control over the community.

Shikwa-e-Hind blissfully disregards this simple truth as if to justify Iqbal’s response to his own Shikwa: “Even an unjust complainant must be conscious of his argumentative shortcomings (Shikwa bejaa bhi kare koi toh laazim hai shu’oor).”

Shikwa-e-Hind: The Political Future of Indian Muslims; Mujibur Rehman, Simon & Schuster, ₹999.

The reviewer is the Secretary General of the Islamic Forum for the Promotion of Moderate Thought.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Books> Review / by A Faizur Rahman / September 20th, 2024