INDIA:

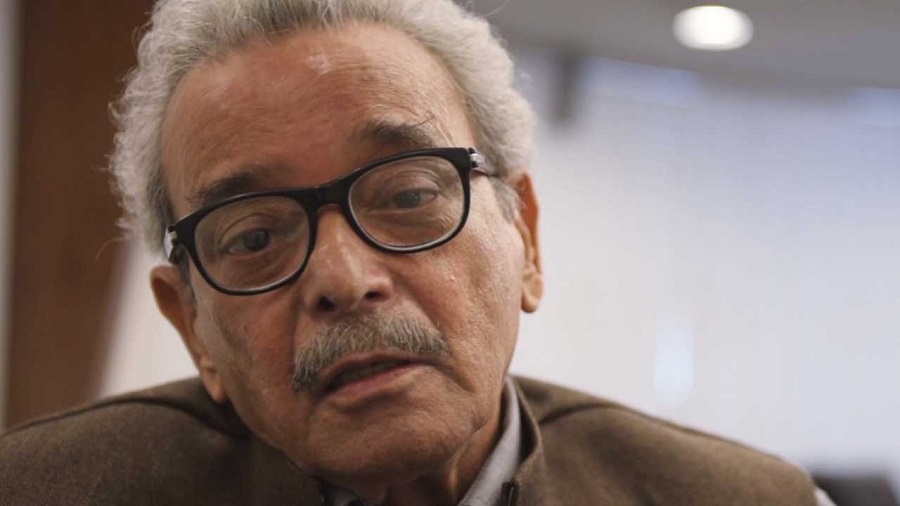

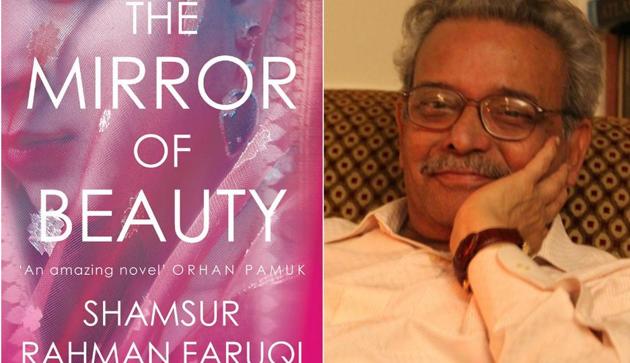

In a new Translating India series, ten noted translators will share their experiences of translating from their respective languages. In this first part, Urdu critic and writer, Shamsur Rahman Faruqi writes about how he translated his Urdu novel into English.

My name is Ka’i Chand The Sar-e Asman. In English, somewhat arbitrarily, I am called The Mirror of Beauty. I am an Urdu novel, a little above 850 pages long. My English avatar is nearly a thousand pages worth of prose of a somewhat quaint register, or registers.

I was somewhat horrified when an author approached me with the proposal to translate me into English. I said: “I hope you aren’t going to do to me what the Bard did to Bottom in A Midsummer Night’s Dream as he casually turned him into a donkey — “Bless thee, Bottom, bless thee. Thou art translated!”

“No, no,” he cried with a tight voice. “Do you doubt my proficiency…?”

“Yes, that too could bear some scrutiny, but my doubt mainly springs from the nature of the beast.”

“You believe I created a monster,” he fumed, somewhat red-faced.

“Do not misunderstand me. In fact, you know very well what you created, and I am quite comfortable with it. Let me remind you…”

“Yes, I know,” he said somewhat testily. “I made you somewhat exotic. I wrote you in about ten different styles, or registers. In general, you are highly Persianised; Arabic is just round the corner almost everywhere. Your narrative language is mostly archaic, so also the dialogues. Most of your women speak what is now called Begamati Zaban, that is, they use words which only women used. You have courtly language in play on almost all occasions in life, from speaking of love to being belligerent, even warlike. Irritatingly, or most piquantly-spicily, your pages are peppered with poetry in Persian or Urdu.”

“Yes, and the professional and technical details, some of them almost untranslatable,” I said.

“Yet you seem to be missing the chief point here,” he said, with his nose in the air.

“And pray, what’s that?” I must confess that I was somewhat nettled by his superior air.

Read the curtain raiser to the Translating India series here.

“Incompatibility,” he said. “English and Urdu are incompatible, and just not grammatically. Urdu’s a genius, especially in the creative modes, is given to elaboration, intensification, abstraction. And Urdu has many more words for emotions; English for all its vastness is remarkably destitute in this area. Take ‘love’, for instance. How many words can you think of in English, including Latinisms and archaisms, to convey the idea of love? Well, just one, or maybe another two or three if you stretch the matter. Urdu has at least 18 words to express the emotion of love. Apart from love too, Urdu’s language of formal discourse has numerous words expressing the same idea with different degrees of intensity or emphasis or nuance. English and Urdu make strange bed-fellows, almost always.”

I felt dispirited. So I will remain hidden behind Urdu’s veil, almost like Lucy, who though fair as a star, lived unknown. But I brightened at the thought that I won’t suffer the mutilation that almost all translations turn out to be. So I said: “Well, then you are saved the trouble of undertaking this back-breaking job, I hope?”

“No”, he smiled his artful, almost crafty smile. “You forget that I am the author, not just some hack pulling an ancient rickety cart of translation.”

“So?”

“First thing,” said he, “As author-translator, I can take liberties, within reasonable limits. I am aware that I am the author of the Urdu novel, I am not composing an original novel in English. But I’ll not let the Urdu text hang too heavy on my translator’s intuitions. Like all translators I’ll give up certain things (like the 18 or so words for love), but will also add certain things.

‘When I sit down to do the English version, I am able to visualise the spirit of the Urdu and almost see it passing into the English words that came to me as I put them then on the page.’

“Most importantly, I’ll exchange the archaic Urdu with a deliberately archaic, passionately and shamelessly 19th century English. I will not permit the entry of a word or usage which came into the language after the time of Victoria, that is, mid to late 19th century. The flavour of the specialised languages and registers of Urdu I’ll give up in favour of translating literally all Urdu words and phrases and make them sound natural to the narrative. I will render the ‘excesses’ of the Urdu into English.”

“And what will you do about the poetry?”

“Well, I am the author, and thus share a bit of the original author’s persona when I quote his poetry.”

It seemed to me that he bared his teeth, somewhat like a dog teasing and enjoying a favourite bone.

“I will translate faithfully, but I’ll use a compromise language – a little modern, a little archaic – to suit the environment of the narrative. And remember, the poetry that I have quoted (and I even wrote some of it, under the names of Dagh, or his mother) is entirely in harmony with the narrative. So, without doing violence to the original, I should produce passable English poems, effective and genuine in their own right.”

“I fear your labours may result into transcreation of some sort,” I said somewhat timidly.

“Transcreation? I defy transcreation. You either translate or create. When I am done, you open any page of the translation, you will recognise the relevant Urdu text instantly.”

“That is something that most translators from Urdu have despaired of,” I said. “How do you hope to do it?

“For one thing, I am fully steeped into the Urdu – its moods, its inner complications, its special characteristics. And I have lived with you for a long time before you came into existence. When I sit down to do the English version, I am able to visualise the spirit of the Urdu and almost see it passing into the English words that came to me as I put them then on the page.”

“But you haven’t even started, how do you know you can do it?”

“Come back after a couple of years and see for yourself.”

A recipient of Saraswati Samman (1996) and Padma Shri (2009), Shamsur Rahman Faruqi is a leading Urdu critic and theorist. The views expressed are personal.

source: http://www.hindustantimes.com / Hindustan Times / Home> Books / by Shamsur Rahman Faruqi, IANS – Indo Asian News Service / February 10th, 2018