UNITED INDIA :

Over the past few years, and particularly after their recent tussle with the government over the statue of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the Ulama’s involvement in politics has come back under scrutiny in Bangladesh. Since the 10th century, the Ulama have been exercising strong authority over religious issues; yet they have been accused of failing to respond to modernity and to the changes in society.

Against this backdrop, the actions, discourses, and history of the Ulama are well worth looking into. Muhammad Qasim Zaman’s The Ulama in Contemporary Islam: Custodian of Change (2002) and Barbara D Metcalf’s Islamic Revival in British India: Deoband, 1860-1900 (2016), both published by the Princeton University Press, are two outstanding studies in this regard. While Metcalf looks into the emergence, proliferation, and responses of the Deobandi Ulama to “modernity” when Muslim power in India was declining, Zaman looks at their strategy to establish authority in British India and Pakistan.

Shifting sands of influence

In pre-British India, religious education was a private enterprise and individual tutelage was the usual mode of the dissemination of religious knowledge. This tradition was to change with the emergence of the Farangi Mahall Ulama as custodians of Muslim intellectual traditions.

The Lucknow-based Farangi Mahall Ulama were known by the family of Mulla Hafiz, who received a land grant from Mughal Emperor Akbar sometime in the sixteenth century. He was the ascendant of Qutbu’d – Din (d. 1691), a Mughal courtier who participated in the collection of Fatawa-yi ‘Alamgiri’. The latter is a collection of Fatwa to be used in the Mughal courts. The family and students who took lessons from this family were known by the name of Farangi Mahall. The activities of the Ulama of Farangi Mahall, however, were confined to producing graduates for princely services. Their most significant contribution was their systemisation of the curriculum—dars-i-Nizami—for religious education. As Metcalf informs us, this curriculum came to Bengal when a Farangi Mahall graduate was appointed as the first principal of the madrasa yi ‘Aliyah’, Calcutta in 1780.

Farangi Mahall’s dominance declined and the centre for religious studies shifted from Lucknow to Delhi by the late 18th century. The person who played a key role in this shift was Shah Waliyu’llah, who advocated for more social and political responsibilities for the Ulama as opposed to those of the Farangi Mahall. Waliyu’llah’s successors had studied legal codes and written fatwa for the Muslim community, which had once become the main tool to disseminate religious instructions when the British were about to establish political authority over India. Besides claiming centrality of the hadith in the interpretation of the sharia, Shah Waliyu’llah discouraged blindly following the rulings of the earlier generations (taqlid). He suggested going back to the Quran or Sunnah for legal solutions.

The 1857 revolution landed heavily upon the revivalist movement initiated by Shah Waliyu’llah. Suspecting the Ulama’s involvement, British colonisers took all religious institutions in Delhi under their control. Fourteen hundred people were shot by British soldiers in Kuchah Chelan, where Shah Abdul Aziz (son of late Shah Waliyu’llah) used to preach, according to Metcalf. The Delhi-based Ulama were forced to move to the countryside and establish a madrasa at Deoband in 1867.

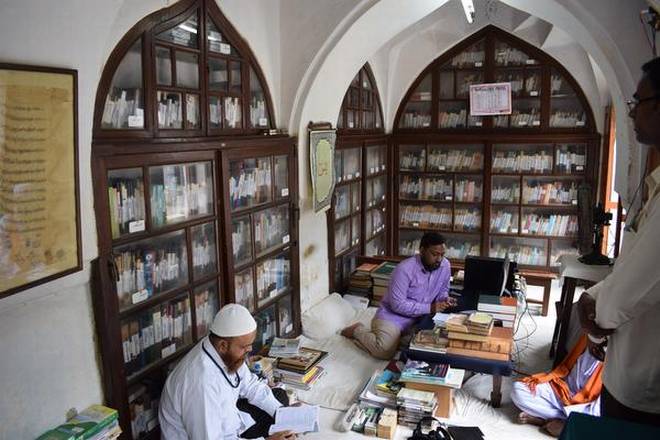

After the revolution, Deoband became the centre for Muslim intellectuals. They introduced formal religious education for Muslims in British India. Students had separate classrooms and a library, and the curricula were organised according to departments, such as Arabic, Persian, and others. A formal examination system was introduced and successful students were issued certificates of award. Graduates came from different corners of India. Most significantly, these graduates went back home and set up madrasas in their respective localities. By the end of the 18th century, nearly every town held the presence of the Deobandi Ulama.

One well known Deobandi Ulama was Muhammad Ashraf Ali Thanawi (1863-1943), who authored Bahishti Zewar (1981)—among the most popular books for Muslims of India, and masterminded the Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act 1939—the first reformist legislation for Muslims of British India.

In the late 19th century, the Ulama played a crucial role in upholding the pride of their religion and their community through publications and public debate on religious issues. Their intellectual exercise peaked with the invention of print technology, multiplying the scale of the transmission of knowledge all over India. Publishing in local languages such as Urdu, instead of Arabic, was one of their effective strategies to establish authority. This also served as a medium of communication between common Muslims and the Ulama, and helped renew Muslim traditions against local customs. Following the birth of Pakistan on August 14, 1947, the Ulama consolidated their authority and forced the then government not to pass a law against sharia. Over the next few years, their continuous efforts would force the Pakistani government to establish a Supreme Sharia Board to oversee any inconsistencies between sharia and laws passed by the parliament.

The historiography of these two books may be compared with Geoffrey G Field’s Blood, Sweat and Toil: Remaking the British Working Class, 1939-1945 (Oxford University Press, 2011), in which Field understands “class” from multi-dimensional approaches including its relationship with the state, society, and family. Similarly, Barbara Metcalf and Qasim Zaman define the Ulama as a class by providing a social and intellectual history of their presence in South Asia. Metcalf highlights their hardships in the post-1857 revolution and the silent “intellectual” revolution of the Deobandi Ulama. Hers is an excellent cultural history. Despite being published earlier, Zaman fills in what Metcalf’s study left to be addressed: it focuses on how the Ulama have played an active role in different social and political contexts, particularly in post-colonial Pakistan. He disapproves of the allegation that the Ulama are against changes. The common mistake that most studies make, says Zaman, is not to consider the social and political context within which the Ulama work. To him, the flexibility of sharia depends on a socio-political context. Zaman suggested that the Ulama do not respond to changes as not because they do not like it but because of their fear of losing authority over religious issues in a modern state.

None of the above-mentioned studies, however, concerns the Ulama of Bangladesh. The growing presence of the Bangladeshi Ulama in the public sphere, particularly their increasing involvement in the political issues, merits investigation into—in Zaman’s words—their “transformation, their discourses, and their religio-political activism.” Could the Ulama in Bangladesh inherit the wind of the Islamic intellectual traditions? The question deserves to be addressed amongst others.

Dr Md Anisur Rahman is a legal historian at Asian University for Women. His research interests include Islam in Asia and South Asian Islamic Law and Society.

source: http://www.thedailystar.net / The Daily Star / Home> Reviews / by Md. Anisur Rahman / January 28th, 2021