KARNATAKA:

Despite the unprecedented popularity of J.K. Rowling’s fantasy novel series, “Harry Potter’ and Jeffry Kinney’s Wimpy Kid series, it is widely believed that the book faces an existential crisis as the dazzling visual culture will soon make it archaic.

The readership of books on different themes in various genres has stagnated. However, contrary to this, young adult literature seems to be a thing of feathers as it judiciously juxtaposes the elemental art of storytelling with poetic sensibilities. If it is short stories or novels, one can find easy-to-understand text structures, different focalizations and multiple narrators with strong moral bearings. In the era of book decline culture, the popularity of children’s literature in verse and prose goes beyond geographical boundaries and language barriers.

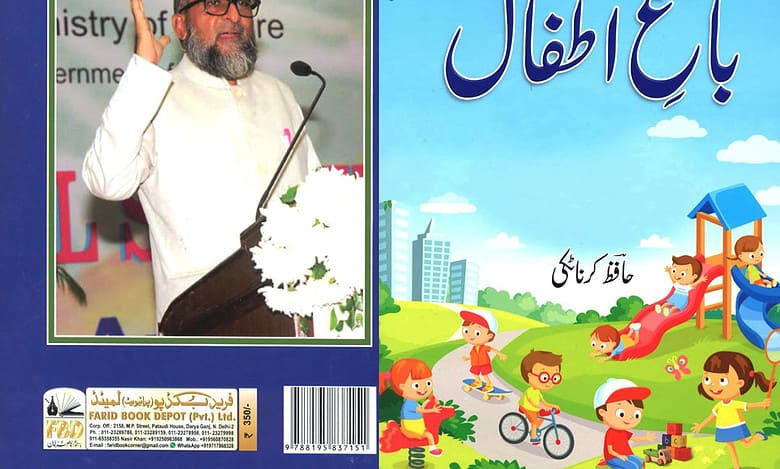

It is heartening to note that the celebrated Urdu poet Hafiz Karnataki has provided the “sweet spot” to Urdu publishing. It did not happen in the famous centres of Urdu literature and culture –Delhi, Lucknow, Hyderabad, Patna and the like; this remarkable feat was achieved by a poet who lives in Karnataka. Recently his hundredth book, Baagh e-Atfal (The Garden of Children), was launched in the presence of eminent Urdu authors and poets, including Khaleel Mamoon, Professor Irtiza Kareem, Professor Ejaz Ali Arshad, Dr Shaista Yusuf, Dr Dabeer Ahmad, Dr Abdullah Imtiyaz, and many others during a three-day national conference on children literature held in Shikaripur, Karnataka.

Hafiz Karnatki, a recipient of the prestigious Sahitya academy award for children’s literature(Urdu ), is an accomplished poet who uses various verse genres such as Ghazal, Rubaiyee, Masnavi, Nazam and others with equal ease. His evocative and multi-sensory verses covering a plethora of themes indicate the ever-increasing range of creative dexterity. He meticulously rendered the life history of the Prophet in verse for children. He made it a point to explain the moral and ethical contribution of the Prophet to humanity. Perhaps he is the first Urdu poet who blazed a new trail in Urdu’s age-long tradition of hagiography by composing it in verse fully alive to children’s cognitive level and expectations. His two books, Hamare Nabi and Zikre Nabi, impeccably summarise the life and teachings of the Prophet.

Hafiz Karnataki is fully committed to fulfilling children’s cultural and literary aspirations and produced nursery rhymes, limericks, short poems and long poems on single topics in a fresh idiom. He gives credit to children for his creative sharpness and cerebral outpourings.” I always strive to stitch up a warm and ceaseless dialogue with young minds, keeping me fresh and mentally alert. Their appreciation and feedback unfailingly hone my writing. As long as this conversation is continued, my literary pursuits bear more fruits,” Hafiz unassumingly asserts.

At the insistence of his young admirers and living up to their expectations, a teacher turned poet Hafiz Karnatki, who has written forty-six books in prose and sixty in verse, started composing much – admired genre of Urdu poetry, Ghazal for children. He compiled six collections of ghazals titled Massod Ghazlen, Nanhi Munni Ghazlen, Bachoon ki Ghazleyen, Ghazal Saaz, Shaane ghazal, and Jan e Ghazal. The poet went further ahead and started meticulously setting ghazals to the tunes and Raags cherished by the children by using Urdu prosody. His verses drawing sustenance from religion, traditions, convictions, cultural, literary and linguistic sensibilities got tremendous applause, and his poems are popular on social media. His latest collection of exclusive poems praising God, Allaho Ahad, has just hit the stand. His hundredth book, Baagh-e-Atfal, carries more than one hundred succinct and didactic poems, zeroes on the topics that directly impact day-to-day life. A distinct tilt towards universal human values and moral framework binds through poems that poignantly harp on different themes. It looks incredible that a person fully trained in traditional knowledge and a scholar of oriental learning has a penchant for new technology. New information technology is an empowering tool that opens its door to all and ushers in a new era of equality. The Internet has subverted the concept of entitled and privileged living, and now everyone is equal as far as the use of technology is concerned. The collection is replete with poems on the tools that shape our lives. Google, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and others surface repeatedly. Spelling out how Instagram lends a helping hand to its users, Hafiz saheb says, “Tehzeeb bhi yahan hain tammadun ke saath saath/ har shai yahan milegi Tawaazun ke saath saath (One can find culture and civilization simultaneously here/Everything is available here proportionately). Why Twitter has become the handiest medium, Hafiz poetically reasons out, “Jo baat Dil mein na rakh sakho bol do yahan /aik aik kar ke greyhen khol do yahan (pour out whatever you can not keep it to yourself/ Untie the knots one by one here).

The latest collection of the remarkably prolific poet Hafiz Karnatki is braced for making an invaluable contribution to children’s literature, and his efforts deserve accolades from all quarters

Shafey Kidwai, a prominent bilingual critic, is a professor of Mass Communication at AMU, Aligarh

source: http://www.siasat.com / The Siasat Daily / Home> Featured News / by Shafey Kidwai / March 23rd, 2023