Bhopal, MADHYA PRADESH :

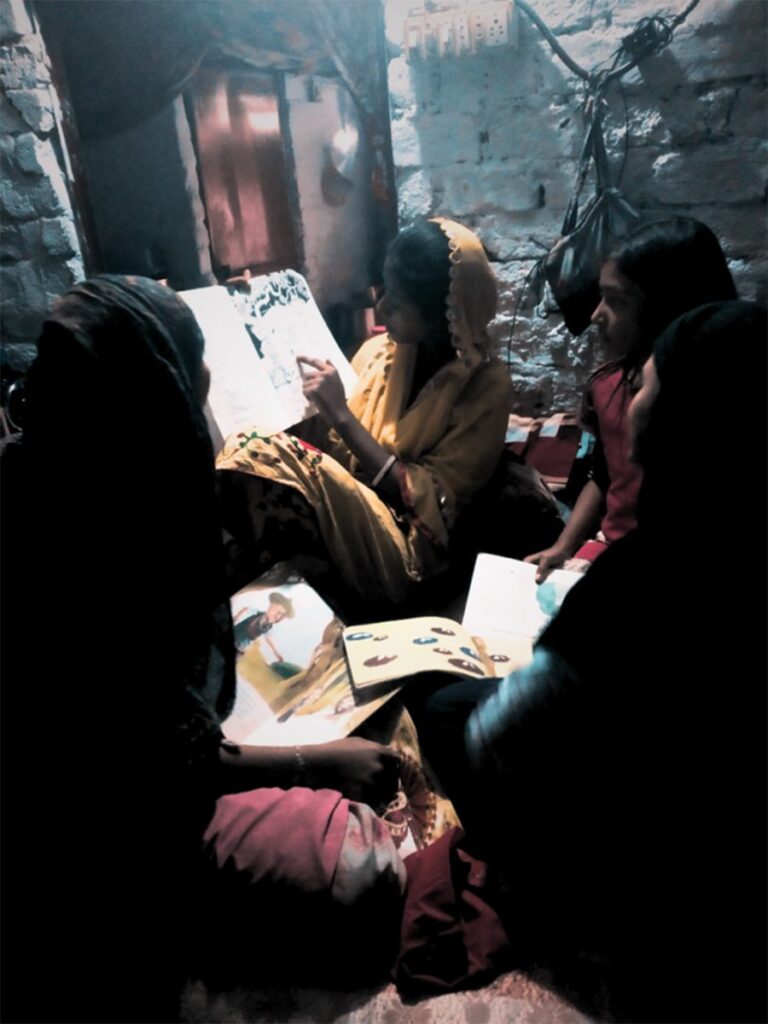

An inside view of the storied, idealistic lives in the Savitribai Phule Community Libraries network

Photo Credit: Saba Khan

Saba Khan has participated in the EduLog programme with The Third Eye for its Education Edition. The EduLog mentored 12 writers and image-makers from India, Nepal and Bangladesh to remember—in the present continuous—their experience of education from a feminist lens.

During COVID, when almost everything was closed in Bhopal, we began delivering books to children by going door-to-door. Adults in the family took to reading those books too. Some girls’ mothers flipped through the pages of the book and looked at the illustrations. When we were giving books to young Rimsha Faiza, her sisters-in-law, who were not very old, came out inquisitively and asked about the books and about Savitribai Fatima Sheikh Library. In Mother India Colony, 14-year-old Saba said, “I am not educated at all. But can you give me some books to read?” Two days later, when I went back to her neighbourhood, she asked, “Can you get me a pad too?”

My friendship with Fiza started with books. When she took her first book, she said, “Next time, please give me two books. Both Rezwan and I will read them.” They were a newly married couple. Then one day she called me and said that Rezwan had beaten her. Fiza wanted me to counsel Rezwan, or else she would kill herself, she said. Perhaps she thought that Rezwan would listen to me—the lady with the books. We connected Fiza with a government-run One Stop Centre that works on the issue of violence against women. Meanwhile, Rezwan also started coming to our library and talking to us. They both complained about each other all the time. I patiently listened to both of them.

Gul Afsha, a mother of two, is a very brave woman. She steals a little time for herself from her kids and comes to the library for a while. She mixes with the other girls in the library and reads poems with great enthusiasm.

Photo Credit: Saba Khan

At the library, Zeba, Joya Tasmian, Mahak, Muskan, and Ilma, all help keep the books. These girls have been regular readers for a long time. When I was thinking of returning to my regular job post-COVID, I consulted with them if they could manage the library without me. They enthusiastically said, ‘Yes!’ At the library, I have often seen women from the community seeking advice about their children or sharing their difficulties with the librarian, no matter how young the librarian is. Among them, 14-year-old Mansi is the youngest librarian. She often imitates the way the older librarians speak. Whenever it is her turn to manage the library, she takes them to the park, forms a circle and reads poems aloud to them. One can already see the qualities of a leader in her.

I was born in Bhopal and grew up here. In 2011, as a social worker, I worked with several government schools under a Tata Trusts programme on education. I realised that often the relationship between teachers and children in schools is one where children sit silently with their fingers on their lips. They read only when the teacher asks them to and then put the book away. I had seen this happening in my school.

When I visited schools under this programme, some of the girls said that they had spoken to their mothers about me and their mothers had invited me home. I thought that this was an opportunity to talk to the children outside of the school. When I met the children in their neighbourhoods, I thought of how much fun it would be if they could read together. And that is how Savitribai Fatima Sheikh Library started.

Even since I was a child, I would always look for books to read. I have always felt that children must have books to read—that they should develop an affection for books and realise that books are their means to know about science, about the world. I used to think that wherever I would go, I would cultivate the habit of reading books in children and gradually, their love for books would grow. But I never imagined that I would see so many libraries opening up and so many educators joining in. Today, we have 11 community libraries across purana Bhopal, including areas like Arif Nagar Basti, Mother India Basti, Madari Mohalla, Bhanpur, Karund Basti and more. We have registered a total of 1,000 children. Twenty educators help run these libraries.

Photo Credit: Saba Khan

We collectively decided to name every library in the neighbourhood after Savitribai Phule and Fatima Sheikh. In a couple of neighbourhoods, boys like Chhotu, Musa and Irfan offered to help in the library. But everywhere else, it was the girls who took charge of the library, its activities and the visitors. In the beginning, we didn’t have tables, chairs, or shelves in our library. Our capital is the people of our community. They are always there to support us and be involved in the library’s future. When we had to move the library due to rain or other reasons, the women in the community created space in their homes and gently said, “Put it here.” In Mochi Mohalla, Sagar’s mother set up a library in her modest shanty where she used to cook food.

Saniya is one of our educators who sets up a library in her home every day. She lives near the Karond Mandi in the Blue Moon Colony where our oldest library used to run. Our library was located in a hamlet that was built on railway land and the place to run this library was given to us by the community. It was demolished by the Municipal Corporation in January 2022. In this situation, Saniya proposed to run the library from her home. She keeps the books and recites stories to children in her home library. She left school after the tenth grade but wants to resume her studies now. She hopes that working with children may convince her mother to somehow delay her marriage.

Jahangirabad is a largely Muslim neighbourhood where we had set up a library. Children who came to the library did not know of Ambedkar. Some called Savitribai Phule ‘Fula’, but some found it easy to pronounce Fatima Sheikh. In some schools, I noticed that they only talk about Muslim freedom fighters (as I imagine they would speak only of Hindu freedom fighters elsewhere). We need to talk about everyone so that children can know how diverse our country is.

Photo Credit: Saba Khan

We consciously try to include this diversity in our libraries. For example, two children from the Mehtar community visited our library. When it was time for them to enrol in school, a group of Muslim girls went with them to help. All the teachers at the school belonged to the upper castes. They commented, “These are Mehtar community children, they cannot study here. They won’t even wake up in the morning, how will they study? Their homes are so dirty.” Eventually, they were denied admission on these grounds. In the evening, everyone sat together in the library and we talked about the reasons behind ‘lower’ caste children being denied education. We decided to speak up as it was our right. The next day, we went to the school again and asked for the admission form. We asserted that our children would study there.

My intention in connecting children with books was also for them to learn to see the world through it. To see and understand the world means to know about the stories behind any discrimination, whether it is based on colour, caste, religion, or anything else.

When we learn about discrimination during the time of Savitribai Phule or Ambedkar, we understand our own biases too. For me, this is the meaning of loving books.

Our educator Tabassum worked continuously for three years to set up a library in Annunagar. Her father runs a madrasa at home where children learn Arabic while wearing scarves and caps. Tabassum believed that the children should learn Hindi and English alongside Arabic. They should also be able to play and move around the madrasa without wearing scarves. So, after her father’s class, she began telling the children to take off their scarves and caps if they wanted to and then she recited stories to them.

We do not keep books that attempt to demean or insult any language, race, religion, colour, caste, class, disability, group or individual. We strive to collect books related to various cultures, genders and people’s lives. Books are categorised according to the age of readers, considering the type of content, images and font size appropriate for each age group. We also have a separate category of books for new readers or those learning to read for the first time.

We have some other rules in our libraries that we tell all our educators to follow. For instance, no educator is allowed to use physical punishment or yell. If a child damages a book, we aren’t allowed to react angrily. We only explain. We do not tell the children how to sit or stand or poke at them generally.

If a child runs away with a book, we do not chase and force her to give it back. We have to trust that she will return it.

Most girls and older children get books issued and take them home. Sometimes, the books get damaged as well.

All the children and adults come together once a month to repair the books in the library. Taping torn pages or sticking them together with glue teaches children to handle the books gently in the future. It also reduces conflict.

Photo Credit: Saba Khan

All our librarians meet twice a month. It’s a treat to share our stories, experiences, happiness and excitement during those meetings. When we sit close to each other surrounded by books, it is like an entire world coalesces at a point. We recite poetry, oblivious to the surroundings or how we are sprawled, arms and legs stretched out. After chatting and singing, we choose books for the next month that can be used in various neighbourhood libraries. We identify spaces where we need each other’s help. We argue and persuade each other. These relationships are now so concrete that these librarians take care of each other’s families, eat out together, hang out during their free time and go out shopping for shoes or jewellery together, despite living in different parts of the city. Our librarians cherish their friendships and the community they have built, as much as the books.

This article is translated by Abhishek Shrivastava.

Saba lives in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh. After completing her postgraduate studies in Child Psychology and Social Work, she has been working with different organisations on issues of girls and women for the last 13 years. Along with this, she independently manages the Savitri Bai Phule Fatima Shaikh Open Library in 11 different resettlements areas of Bhopal.

source: http://www.thethirdeyeportal.in / The Third Eye / Home> Praxis / by Saba Khan / February 14th, 2023