Barabanki District, UTTAR PRADESH :

This is just not another memoir of a politician happily or unhappily bounds to look back; the author, instead, talks like a grandmother narrating a story of post-independent India somewhat interlinked with the Congress.

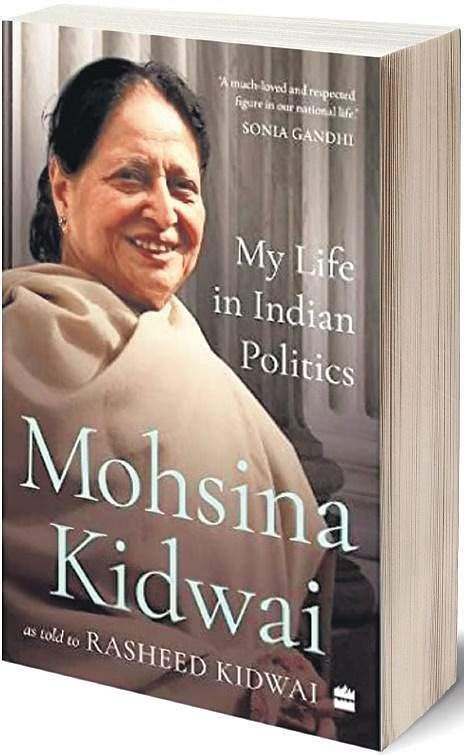

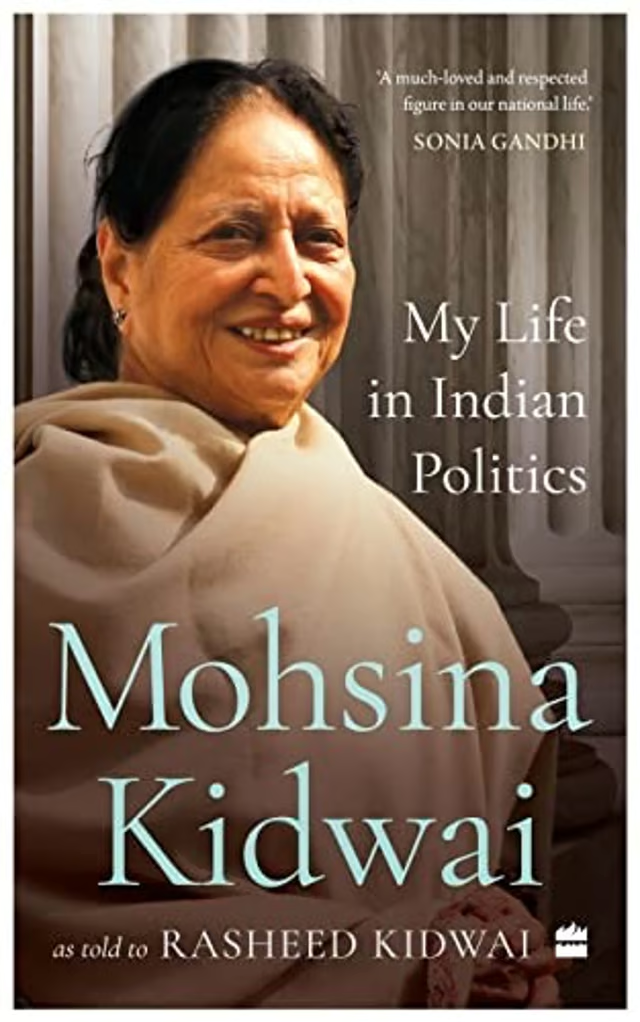

Mohsina Kidwai, author of the book ‘My Life in Indian Politics’

Book Review: Non-fiction (Memoir)/2022; My Life in Indian Politics by Mohsina Kidwai (As told to Rasheed Kidwai); HarperCollins, 300pp (Hardback)

Indian politics is a sort of ‘wonder’ and its unique existential positioning can’t be imagined without people behind its ups and downs. Reading the memoirs, especially of those who served in public life for long, is amongst the rewarding pastimes of a reader. I read Mohsina Kidwai’s memoir as a manuscript, and of course, I reread it even more carefully in its print version. Here is a candid account of a prominent political figure of India who dispels the stereotyped traditional notions that are usually expected to be self-centred and being extra boastful in the first person narrative.

Mohsina Kidwai has been in public life as a member of the Indian National Congress for over six decades. A cabinet minister in several successive central governments and a senior office-holder in the Congress, she has had a ringside view of Indian politics for almost the entire span of independent India’s existence. She has witnessed, and been a participant in, the tenures of prime ministers from Jawaharlal Nehru to Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi, and was a member of parliament until 2016, one of only twenty Muslim women to have been elected to the Lok Sabha since 1951. She has had a prolific track record that can’t be compared with her fellow women politicians, more so, from the Muslim community.

My Life in Indian Politics by Mohsina Kidwai

The book reflects well on her long and eventful life in politics and covers quite skilfully her contributions to public life, and also succeeds in providing an honest appraisal of the turn in fortunes of the political party she has remained a loyal member of over the decades. The author along with co-author and senior journalist Rasheed Kidwai, endow the readers with rare glimpses to homes, lives and hurly-burly of election campaigns from bygone era when Congress dominated the political landscape at centre and in the states.

One such memorable one was the Azamgarh bypoll in 1978, which Mohsina Kidwai won as Uttar Pradesh Congress Chief, and which signalled a revival of the Congress’s fortune after its spectacular defeat in the post-Emergency general elections of 1977. The book’s cover informs you and inside, the details and rich and beautifully presented.

We get to see little known facts about India’s Prime Ministers Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Lal Bahadur Shastri, Indira Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi and P V Narsimha Rao. Similarly, she is forthright in accepting that her move to join the breakaway Tiwari Congress in 1995 was a mistake.

Here is a quick recap of a few of them:

Mohsina Kidwai talks about an incident which happened when Lal Bahadur Shastri had visited Barabanki sometime in the early 1950s. “A few years after marriage, I saw Shastriji, who had come to meet my father-in-law. Jameel ur Rahman Kidwai Saab had stood for elections and Shastriji was canvassing for him. Shastriji was a simple man. Our domestic help, who did not recognize him, asked him where he was from. Shastriji, by then already a Union minister, replied that he had come in connection with the election and wished to meet Jameel Saab.

“He will return home in the evening,” the domestic help told Shastriji and asked him to wait. Shastriji waited. The servant served him tea.

In the evening, when my father-in-law returned, he saw Shastriji waiting.

A little embarrassed, my father-in-law scolded the servant for not informing him about the guest. After that Shastriji became a member of our extended family.”

Some rarest accounts on Indira Gandhi:

“Indiraji was extremely caring and attentive. I can go on talking about many instances. Sometime after the 1977 Lok Sabha polls when Indira ji was in opposition, she planned to visit Badrinath for puja. I and Narayan Dutt Tiwari and I accompanied her. It was an October month. We were told that puja starts at 4 am. Asking us to wait, she went to the temple for Puja. We were to start at 6 am on the return journey to New Delhi. At 5 am, Indiraji returned from the temple and checked whether all the vehicles of our convoy were ready. The pundit of the temple offered us breakfast. When we were having breakfast, the drivers were heating the engines of their respective vehicles. I told Indiraji, we had breakfast but poor drivers must be hungry. They have not even had tea as they were busy heating vehicle engines. I suggested we stop at the first tea shop in return for the drivers to have tea. She agreed.

Indiraji had the habit of carrying some snacks with her in a basket during travel. After a while I saw her taking out some biscuits from the basket kept beneath her seat. She tore the biscuits in four pieces and asked the driver to pick the pieces one by one from her hand while driving. She extended her hand carrying biscuit pieces and the driver did what he was told to do. Indiraji used to enjoy such affection and spontaneous display of it that it often stunned me and used to fill my heart with admiration and pride for my leader.”

“Indiraji could also sense what people around her were feeling. Once we were traveling by an overnight train to Gorakhpur and I suddenly realised I was alone with the Prime Minister in the first-class coupe. She sensed that I was a little uncomfortable and directed me to turn my face towards the wall and go off to sleep,” adds the author.

Undeniably, the book is written with honesty and simplicity, and should be better known as a work to assess an entire era in Indian politics. This is just not another memoir of a politician happily or unhappily bound to look back. She, instead, talks like a grandmother narrating a story of post-independent India somewhat interlinked with the Congress. The book is essential reading for anyone interested in knowing India, its democracy and the foundational stories of a remarkable journey.

(The author is a policy professional, columnist and writer with a special focus on South Asia. Views expressed are personal.)

source: http://www.outlook.com / Outlookindia.com / Home> Culture & Society> Book Review / by Atul K Thakur / January 07th, 2023