DELHI :

Iqtidar Alam Khan’s Latest Books on India’s Medieval History Unearth Hidden Secrets

Iqtidar Alam Khan’s first slim book, a biography of Humayun’s brother Mirza Kamran was published in 1964; his latest book, slightly bulkier than the first, has been published in early 2021 when he is nearing 90, with nearly a dozen authored and edited volumes in-between. Quite an emphatic comment on how prolific he has been in his distinguished career as a historian of medieval India! Add a very distinct quality of the huge range of themes and the empirical solidity of his researches and one begins to appreciate the indelible imprint on the study of medieval Indian history he has left for his own and future students.

Professor Iqtidar Alam Khan was an alumnus and later faculty of the department of history at Aligarh Muslim University when it shone like the pole star in the study of medieval Indian history under the leadership of frontline scholars like Professors Mohammad Habib, Nurul Hasan, K. A. Nizami and Irfan Habib; he himself added to its lustre, evident in his extensive explorations of different facets of his discipline. This, when he always avoided drawing attention to himself.

The range of his explorations is amazing: biographies of two Mughal nobles, “Turko-Mongol theory of kingship” which had a decisive influence on Mughal notion of sovereignty, the system of revenue assignment of Akbar.

The classic essay on “Akbar’s nobility and the evolution of his religious policy”, which was a sort of watershed intervention in 1968 in that it set new terms for the study of the Mughal “religious policy” and has stood the test of time, some feeble recent challenges notwithstanding, the pioneering studies of gunpowder, guns and artillery and not least the bringing to attention some Persian language texts. However, all this work pertained to the Mughal period of Indian history.

Attention to detail

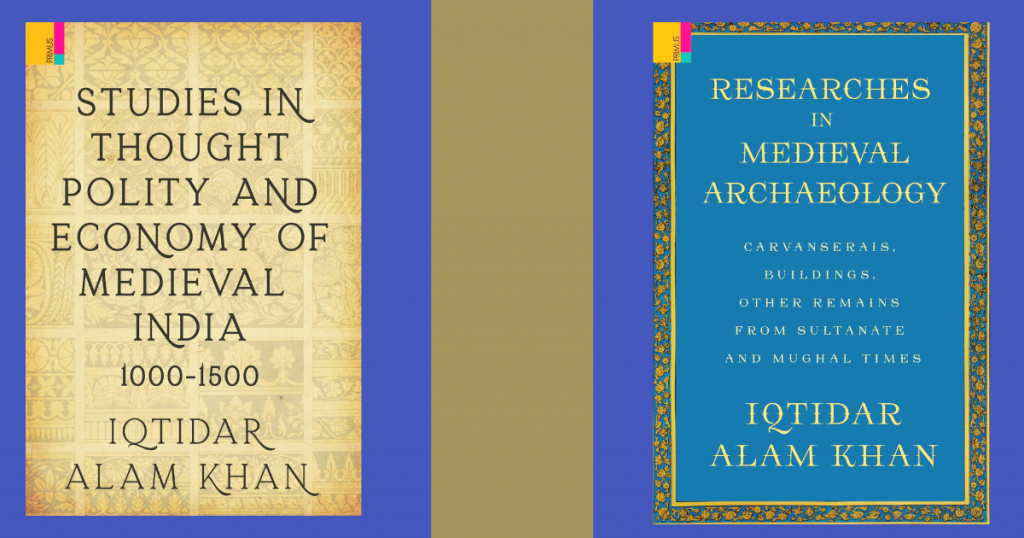

This current year has, however, revealed two hitherto unknown facets of his scholarship with the publication of two books in quick succession, both by the venerable publishers, Primus: Studies in Thought, Polity and Economy of Medieval India 1000-1500 and, hard to believe, Researches in Medieval Archaeology.

The first brings to us his mastery of various themes from the Delhi Sultanate era with the same eye for empirical soundness of every detail as his works on the Mughal period, though still tied to the Court and its outliers except for a revisit to Alberuni’s ‘concept of India’.

It is the second work that takes us literally to the ground level, taking us through the dust and grime of small buildings, remains of centuries-old Sarais (inns), waterworks, indigo vats, dykes and fascinatingly the ‘city’ built by Sultan Muhammad bin Tughlaq which he had named Swargduari, Gateway to Heaven, in district Etah in present day Uttar Pradesh.

Traveling in ramshackle vehicles for nearly two decades, Professor Khan along with his team, dedicated himself to recovering and recording the remains of small, virtually forgotten buildings of various kinds – calling them monuments would be grandiose – in every little detail of location, dimensions, recoverable history from texts and from folklore. It was remarkable labour of love where his age and family’s pleas could not hold him back.

The introduction, besides bringing the reader up to date on the theoretical backdrop of archeological study makes the valuable plea that one should embark on field exploration only after running through all the relevant textual material available for imparting completeness to the exploration.

While for all the sites studied included in the book have almost every kind of technical detail have been recorded, the last and longest chapter, dealing with Sarais is the most fascinating in that it opens up a number of windows to the social history of the period. It reveals that the state took upon itself the task of promoting travel as well trade, and at a certain stage postal service, by constructing inns and rest houses all along the trade routes. The task of constructing inns starts as early as Asoka’s time, for it is mentioned in one of his edicts, but later history on the theme is obscure.

In medieval India, references to these, along with milestones, kos minars resume from Sher Shah’s time and continue into the 18th century. The title Sarai is scattered all over the land with prefixes like Ber Sarai, Arab ki Sarai, Katwaria Sarai, Sarai Kale Khan and numerous others in Delhi itself, not to forget the Mughal Sarai, its history now erased through political diktat.

The very spread of these is suggestive of both the extent of travel and trade and state’s assumption of responsibility for providing security and patronage for it. The lodging and boarding at Sarais were often complementary and at times chargeable.

Luckily for the historian, the travelers at times left some graffiti on the walls noting their identity, several of which have been copied in the book. Where boarding was provided, separate kitchens were run for the Hindu and the Muslim travelers, suggesting that they came from both communities and shared the space but maintained differences in food, which was recognised and accepted by the state.

It also suggests that the difference did not turn into hostility. The book reproduces one graffiti in Devnagari on the wall of a mosque by one Kishan Das wald (son of) Maha Nand Kambu of Agra; he had obviously found shelter at least for a night at the mosque which he appears to have gratefully recorded; this reminds Professor Khan of Goswami Tulsi Das’ reference to “sleeping at a mosque”!

These two books, the second one, in particular, is a delightful revelation of an attractive aspect of an extremely reticent scholar of great eminence: dedication without seeking recompense in the form of the fanfare of recognition, but pure dedication to the unearthing of history’s hidden secrets without a trace of prejudice or preference. Dedication that cuts across compartmentalisation of Delhi Sultanate versus Mughal Empire, economic history versus political history, archeology versus textual narratives and so forth. A dedication that does not tire with age.

We are grateful to Professor Ali Nadeem Rezavi, who as head of the department of history and in-charge of its section of archeology persisted with Iqtidar Alam Khan to collect all his scattered data and reproductions of photographs of remains and graphs prepared to put together in a book; we owe a big debt to him for succeeding in the effort.

Harbans Mukhia taught medieval history at JNU.

source: http://www.thewire.in / The Wire / Home> Analysis> Books> History / by Harbans Mukhia / May 11th, 2021