BIHAR / Lucknow, UTTAR PRADESH / NEW DELHI :

Sometime last summer, Resham Fatma, 17, decided that she needed to score 98 per cent in her twelfth standard board examinations. For days, she had been scouring the newspapers to find the best college to pursue her favourite subject, mathematics. St Stephen’s College, Delhi, it was. “Last year’s cut off was 97.2 per cent, so with 98, it will be smooth sailing,” says the Lucknow girl.

Resham has planned her future in detail. After graduation, she will do an MBA from IIM-Ahmedabad. Then, she will take the Union Public Service Commission exams, get into the Indian Administrative Service and work towards the post of district magistrate, a post from which she believes she can implement all the glorious government policies that remain on paper. “If I set my mind on something, I can achieve it,” she says. But, the future does not always work out the way you plan it. The last year has been, to put it bleakly, scarring for Resham.

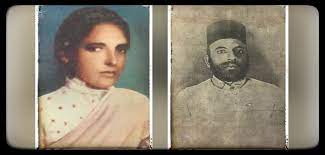

The day is etched into her memory. It was February 1. On the previous day, her class had given their seniors a formal farewell. Her hair was a curtain of black satin, glossy from all the shampooing and conditioning. “See, this is me, in the centre,” she says, fishing out her smartphone and showing a groupfie with friends at the farewell.

The next day, she headed for her tuition, getting off the autorickshaw and walking the last mile as per routine. Suddenly, Riyaz, 38, her mother’s cousin, pulled up in his Tata Indica. He had been pestering her for a few years, and she had learnt to avoid him. On farewell day, he had asked her to meet him and she had said, “Main pagalon se baat nahi karti [I don’t talk to madmen].” She had no idea how mad he was.

After dragging her into the car, he held a butcher’s knife to her throat and asked her to marry him. She struggled; he got forceful. When she loosened his grip on the knife, he pulled out a barber’s razor from under the seat. “The car was auto-locked,” she says. “I was in his grip, struggling with all my strength. He banged his head on the steering and asked why I was refusing him. Then, suddenly, he pulled out a plastic bottle from the recess in the car door. It was filled with a yellowish liquid. He asked me if I knew what it was and said it was shakkar pani ghol [sugar solution]. He poured the liquid over my head.”

For a fraction of a second, she did not know what it was. Then it began to burn and she immediately shut her eyes. Her face, arm and thigh were on fire. He pulled her by the hair, still holding the knife to her throat. “I do not know how I got this phenomenal strength at that moment,” she says. “I pushed him and he crumpled towards the door. I fumbled blindly with the ignition, unlocked the car and tumbled out.” It was a dark winter evening and the road was desolate. Presently, an autorickshaw drove by and she pleaded to be taken to the police station. Luck was on her side, the occupants rushed to help. Later, as she was taken from the police station to hospital in an autorickshaw, they had to stop at a railway crossing. Passers-by peered into the auto, clucking in sympathy or gasping in horror. “That’s when I learnt that my face was black and I had my first shudder,” she says. “Riyaz mama ko mat chodna [Don’t let Riyaz get away], I screamed.”

Resham had so far known only unconditional love. She was the eldest grandchild from her maternal side, and her mother’s brothers doted on her so much that when she entered primary school, she moved from Bihar, where her father is an automobile dealer, to her grandfather’s residence at Amausi, near the Lucknow airport. Both her uncles have sons, she grew up as the only girl and the apple of everyone’s eyes. She has a younger sister and brother, who live with her parents. “I am more comfortable here, this is my home,” she says.

Resham means silk. But in the months ahead, the teenager discovered reserves of steel within her. Her long tresses were shorn, there is a huge patch on the scalp where follicles are dead. Resham, for the first time in her life, started wearing a scarf and headed for her evening coaching. She had to skip regular school at Stella Maris; her skin was not ready to face the onslaught of the sun.

In between, she kept popping into the hospital for surgeries. Her thigh needed grafting and her face needs a lot more work, but that has not deterred Resham from going out with nonchalance. A few months after the incident, her uncle declared she could do her own shopping without being escorted around like an invalid. “People ask me what happened, most ask whether it’s an allergy,” she says. “I tell them blankly, ‘No allergy, I survived an acid attack.’’’ Does she miss her old face? “Well, I am a girl, I like looking into the mirror and I’d want to like what I see,” she says. “I am still not bad looking, am I? This is my new identity.”

Most of her friends broke down when they visited and she consoled them. Her best friend is her diary. One day, she wrote about her dream: “I wanted to become the district magistrate and visit Riyaz in jail and tell him, see where you are today and where I am.” But these Bollywood-type situations are not meant for off-screen lives, even if they are as extraordinary as Resham’s.

Riyaz was arrested and was in lockup, where on December 28, he committed suicide. “I read about it in the newspaper next day and felt blank,” Resham says. “He got away so easily. He should have lived a long life, regretting every moment.”

Her earliest recollections of Riyaz are of sitting on his shoulders as he ran across the lawn. As she grew up though, his presence began getting uncomfortable. He would enter her room, force her to leave her books and talk to him. At one point, her grandfather, a former policeman, banished him from their house.

Resham today prefers to look at the possibilities that the future offers. “I have bad days, though I don’t cry in public,” she says. “Some days ago, I was very angry with Allah pak. But then, I got this call from Delhi that I was getting the Bharat Award at the Republic Day celebrations. I am so happy today. I have met big people, Modiji himself. I am a heroine, isn’t that great?” The scar tissue on her face hurts a lot, especially when she has to receive injections for treatment. But now she is complaining happily about how her cheeks are hurting with the constant smiling. “I am posing for cameras all day. Yaay,” she shrieks.

There’s a bit of regret, though. “When I came to Delhi, I learnt that all the other children had been felicitated by their states. But no one from my state government ever came to me. A Supreme Court order says the state has to give an immediate relief of 03 lakh to an acid attack victim. I have not got anything yet, though my family has sent several Right To Information pleas. We could afford my treatment, but there are those for whom this money means a lot more. You know, there is a lot of good intent and great laws, but what we lack in this country is implementation. That’s why I want to be an IAS officer,” she emphasises with all her Taurean determination.

source: http://www.theweek.in / The Week / Home> Web Specials> Features> Heroes / by Rekha Dixit / Headline Edited + Additional image inserted courtesy of Facebook.com/Muslims.of.India.page / February 08th, 2015

.webp)