INDIA :

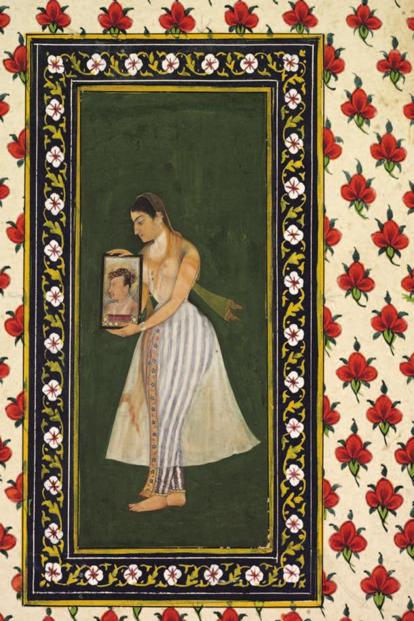

In an interview with Indianexpress.com, Lal spoke about the incredible achievements of Nur Jahan. Remnants of imperial orders issued by her, coins minted in her name, paintings that paid ode to her sovereignty and bravery are all evidence of the enormously powerful figure she was.

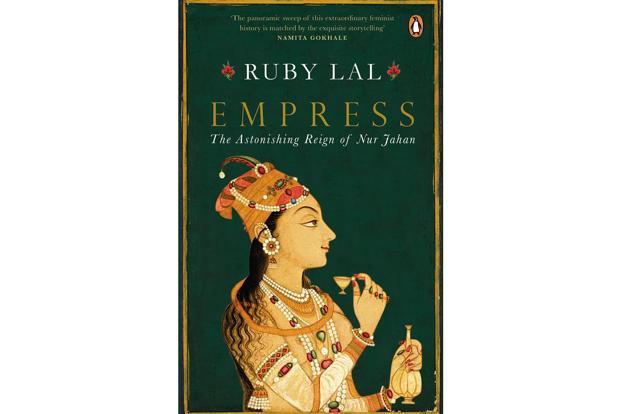

For four centuries, from when she was at the centre of one of the largest empires of the world, Nur Jahan, the twentieth and supposedly the most loved wife of Mughal emperor Jahangir, has been a household name in the Subcontinent. Though she was not officially the ruler of Mughal India, Nur Jahan has been noted by historians to be the real power behind the throne. A politically astute and charismatic figure, she ruled Mughal India as a co-sovereign of Jahangir and is known to have been more decisive and influential than he ever was. Historian Ruby Lal in her latest book, ‘Empress: The astonishing reign of Nur Jahan’, dives deep into the intriguing world of the only woman to have helmed the Mughal empire. Tracing her life in great detail, Lal attempts to rip apart narratives of romance and exoticism that surround the image of Nur Jahan and focus upon what made a Muslim woman living in seventeenth-century India, one of the most authoritarian figures in Indian history.

In an interview with Indianexpress.com, Lal spoke about the incredible achievements of Nur Jahan. “People say she always sat right next to Jehangir in the court and that if some cases or decisions came up and if she agreed with him, she would pat him on the back and he would say yes to that decision,” says Lal who is Professor of South Asian Studies at Emory University in Atlanta. Remnants of imperial orders issued by her, coins minted in her name, paintings that paid ode to her sovereignty and bravery are all evidence of the enormously powerful figure she was. Charting the life history of Nur Jahan, and placing her in the background of the pluralistic cultural space that Mughal India was, Lal puts together an evocative biographical account of the queen.

Here are excerpts from the interview with Lal.

Popular perception of Nur Jahan is somehow constricted to the romantic relationship she shared with Jahangir. Why is that the case?

There is a very long history of the erasure of Nur Jahan’s power that I chart in the book. As she traveled through the length and breadth of the country with Jahangir – issuing imperial orders, hunting a killer tiger near Mathura, discussing the expansion of the empire- she rose to being the co-sovereign. This does not mean that in her own time people did not raise eyebrows. In 1622, her stepson and Jahangir’s son Shah Jahan had risen in revolt. The catalyst for his revolt was the moment when Nur Jahan arranged a match for her daughter from her first marriage, Ladli; she chose the youngest prince, Shahriyar for her. About that time, Shah Jahan went into rebellion against Jahangir. And its is very clear that he felt threatened; he knew about the power of Nur Jahan. In fact, Shah Jahan and Nur Jahan had been closely aligned. The year 1622 is when certain chroniclers begin to write about the chaos that Nur Jahan Begum had raked up between the father and son.

So the early criticism appears to begin around this time. The other major moment of critique of Nur’s power was when they were on their way to Kashmir and Mahabat Khan (who went on to capture Jahangir later in 1626) goes on the journey with them to a certain distance and according to one of the chroniclers he says to Jahangir that a man who was governed by a woman is likely to suffer from unforseen results. In 1626, she, completely visible, goes to save Jahangir (sitting upon an elephant on a roaring river), commanding all men including her brother Asaf Khan. She stratergises and eventually saves the emperor. After this, we begin to come across a word called Fitna, in the records.

Fitna is a very loaded term in Islamic history. It is used for the first time during the Shia-Sunni split for civil strife. It was also used against Ayesha, Prophet Muhammad’s favourite wife, when she went on a battle against Ali who was eventually the leader of the Shias. Over time, the word came to be used against women’s visibility, their sexuality and so on. Following 1626, this is one word that is used repeatedly against nur – that is to say that her power produced chaos.

Later, in the Shahjahanama, we find that at one point that the chronicler lists her power as a “problem”: the Shahjahanama reverts to the male inheritance of power and completely undoes her co-sovereignty with Jahangir.

Then there were also visitors to India like Thomas Roe, the ambassador of James I of England who follows Nur and Jahangir through the camps in Gujarat and Malwa. He calls her the Goddess of heathen impiety.

In the 19th century orientalist renditions of the romance of Nur and Jahangir become very important in the histories of the time; later, the colonial renditions highlight and forward such stories. Nur Jahan becomes classic oriental queen. Thus, a long-standing history of the erasure of the power of an astonishing emperess. It is certain that the erasure of Nur’s power travels into modern times and we only hear about her romance with Jahangir, not about her work as co-sovereign of the empire.

Jahangir is often compared with Akbar and criticised for being an uncompetitive, flamboyant king, who spent much of his time in drinking and merrymaking. But the fact that it was during the reign of Jahangir that a woman became so powerful, what does it say about his attitude towards women?

You are right, this is how Jahangir has come to be imagined. There are a range of scholars who for sometime now have been rethinking Jahangir’s reign, his philosophical and artistic engagements. My book foregrounds the ways in which Jahangir seeks to go differently from how Akbar articulated his sovereignty. If you look at the reigns of Babur and Humayun, there was no stone harem: the kings were nomadic and forever on the move. During Akbar the Great, for the first time in Mughal history, the imperial harem is built in stone in Fatehpur Sikhri. For the first time in the Ain-e-Akbari, women are declared as ‘pardeh-giyan’ which means “the veiled ones.”

But what Jahangir does is that he goes back to the ethics of Babur. He was constantly wandering, he was constantly moving. The ethics of a peripatetic life and movement, which contributed to the co-sovereignty of Nur Jahan. Nur Jahan is the biggest example of Jahangir’s attitude towards women. An 18th-century chronicler that advances the Jahangirnama to the end of Jahangir’s death had suggested that the emperor had once claimed that he had given the sovereignty to Nur Jahan Begum and that he was quite content with his wine and meat. It’s an allegorical statement: and one indicates his admiration of Nur, something that he chronicles in his own memoir

Would Nur Jahan be this powerful had she not been married to Jahangir or had she not been part of the Mughal empire?

I think, Nur Jahan, looking at her whole life history and context, would have expressed her power differently in other circumstances. Her life history shows her dynamism and boldness. Of course, as I have been saying, and detail in the book that the plural landscape of Hindustan was very important- in that that it fostered experimentation and all sorts of ways of being (alongside war other challenges of co-existence of multi-confessional identities). We should also remember that she comes from an important Persian family background, deeply invested in poetry, arts, calligraphy. Then her own initiative must be highlighted: there were other women in the harem – and indeed Nur walks in the tracks of these women’s power – but no one becomes a co-sovereign. That speaks something about her boldness, her endeavours and of course her ambition.

Islamic societies are often noted to be more regressive compared to others in their treatment of women. In your book do you try to subvert this notion?

I Am trying to suggest that Nur Jahan is the history of India. She was a Shia married to a Sunni Muslim who was also half Hindu Rajput. Further, Nur Jahan is the only woman ruler among the great Mughals of India (there are technical signs of being a sovereign and informal signs, both of which I detail in the book). That is the history of India. As far as Islam is concerned, people should know that there were incredible and powerful women in Islamic history all the way through. We have Ayesha, Raziya, we have Nur Jahan Begum, we have any number of powerful women. It is also the multicultural world. In the modern world, we tend to think in terms of fixed identities. People in early modern times were much more open. Jahangir was engaging with Siddichandra, a Jain monk. Nur Jahan used to tease him about the pleasures of the flesh. What does this tell you? It tells you about an open engagement. It tells you about how experimental Islam is, how mixed Islam is, how vibrant Muslim women are and how Islam is so deeply attached to India.