Leh, LADAKH :

Noor Jahan and her cousin Wajeeda Tabassum co-founded Shesrig Ladakh, an art conservation practice that restores and conserves ancient wall paintings, religious manuscripts, thangka (Buddhist scroll) paintings and metal works.

How do you protect and preserve culture? It’s a question Noor Jahan – a 32-year-old expert in art conservation and heritage management from Leh – has grappled with for a decade.

Through Shesrig (meaning ‘heritage’) Ladakh, an art conservation practice she founded with her cousin Wajeeda Tabassum, Noor performs critical restoration and conservation work on ancient wall paintings, religious manuscripts, thangka (Buddhist scroll) paintings and metal works.

“My real interest lies in working on ancient wall paintings and thangka paintings,” says Noor Jahan in a lengthy conversation with The Better India.

Backed by a Master’s degree from the Delhi Institute of Heritage Research and Management (DIHRM) and a PhD from the National Museum Institute, she has worked on wall paintings dating back to the late 8th century and Buddhist thangkas from the 19th century. Also, since 2019, she has run Shesrig on her own following Wajeeda’s departure for foreign shores.

What’s more, Noor is also the goalkeeper for the Indian women’ ice hockey team. Earlier this year, she helped India finish second in the Union Women’s Ice Hockey Tournament in Dubai. Noor reckons that she has a few more years left before she “officially retires” from the sport.

By all accounts, it’s an extraordinary way of life, and this is her story.

Noor Jahan working on old wall painting in Saspol caves, Ladakh

A serendipitous journey

There was a void in Noor’s life after earning her bachelor’s degree in commerce from Delhi University. Going through the motions, she had no passion for what she was learning. To reflect on what was next and enjoy a short holiday, she left for Leh after graduation in 2011.

It was during a walk through Leh’s crowded old town, when she met a few foreign conservators from the Tibet Heritage Fund working on an old Buddhist temple. Intrigued by what they were doing, Noor engaged in a short chat with them which would change her life.

After returning to Delhi, she began reading up on art conservation and learnt that she could pursue higher studies in this field.

What also sealed the decision to get into this field for Noor were memories from her childhood.

“My mother is from Hunder village in Nubra. Every holiday, we would always visit Nubra to meet my maternal grandparents. The bus would stop at this location called Chamba on the main road from where you had to walk inside the village. This particular route holds great importance in my life now because there are many stupas along the way. Every time I would look up at these pathway stupas, I would see these old paintings. But each passing year, some part of these paintings would disappear. When I applied for this course at DIHRM, the first thing I thought about were these paintings and the conservation work I could do someday,” she recalls.

Allied with a strong desire to come back home, starting this course brought passion back into her life. “Everything I was studying there found a purpose in Ladakh,” she says.

Noor Jahan found purpose in preserving Ladakh’s heritage

Finding Shesrig

Following the first year of her Master’s programme in 2012, Noor and Wajeeda opted to do their internship with the Himalayan Cultural Heritage Foundation (HCHF), a Leh-based non-profit. Helping them find projects to work on was Dr Sonam Wangchok, founder secretary of HCHF.

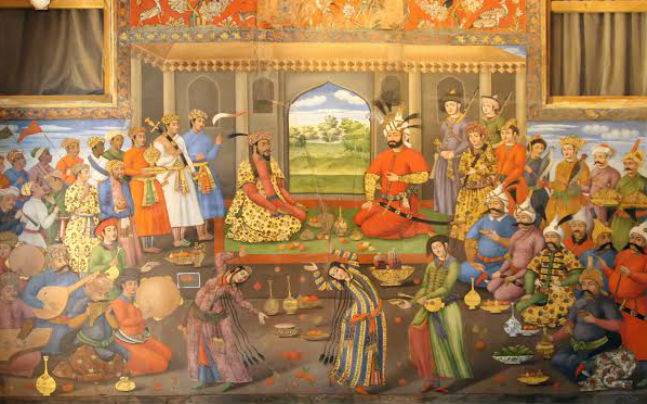

During this internship, the first major project Noor got involved in was a wall painting at Diskit Gompa, a 14th-century Buddhist monastery in Nubra Valley.

She recalls in an Instagram post, “The internship entailed working on the restoration of wall paintings from the 17th century under the supervision of art conservators from [the] Czech Republic. This was my first hands-on experience where I had the opportunity to conserve sacred Buddhist art and the opportunity to stay at the monastery itself. I think that internship changed my life forever as I not only got to work on the most beautiful wall paintings but gave me the opportunity to meet and interact with the monks at the monastery who took me and Wajeeda in as their own.”

Conserving ancient wall paintings is a delicate process

After completing her Master’s programme in 2013, Noor came back to Leh to work with other organisations like Art Conservation Solutions and Achi Association, amongst others, as a freelancer. In 2014, she worked on her first project outside Ladakh at the Golden Temple in Amritsar with Heritage Preservation Atelier, and also commenced her PhD at the National Museum Institute. Despite these landmark moments, she knew this sort of freelance work wasn’t sustainable.

“Working in these organisations was a great learning experience and helped me to capture some of the finer nuances of conservation. Even today with Shesrig, I collaborate with most of them. But this kind of work wasn’t sustainable, i.e. it was limited to summer months,” she says.

“In the summer, I would work on many projects. But the moment winters came, all these organisations would stop their work in Ladakh. I really wanted to start something of my own in Leh, while working sustainably and throughout the year,” she adds.

Thus, in 2017, Noor and Wajeeda founded Shesrig Ladakh and rented out a historic structure called Choskor House as their base in Leh’s old town, which they had to first restore.

This three-storied structure is located right behind the Jama Masjid (mosque) in the centre of Leh along the hillslope. It belongs to a renowned family of traders, who along with other important families, once led important trade missions to Lhasa from Ladakh.

“Even though Choskor House was really old, we decided to rent it. To restore it, we had initially consulted some architects, but there came a point when it became difficult because of costs and time constraints. That’s when we reached out to Achi Association India, a sister organisation of Achi Association (a Swiss-based organisation), which took over the project of restoring this structure backed by funding from the German Embassy. They helped with establishing the studio in which we currently operate. We started working inside our studio only this year,” says Noor.

“It’s important to see your heritage as an inheritance that has great value,” says Noor Jahan

Conserving ancient wall paintings is a delicate process

Conserving wall paintings

Conservation and restoration are different acts. Noor explains, “In conservation, people do not recreate anything new. So, if there are losses in a given wall painting, there is no recreation but only stabilisation. Restoration, meanwhile, seeks to recreate some of those losses.”

Some of the fundamental challenges in conserving or restoring old artworks include physical access to remote sites and obtaining the necessary materials that they largely import.

Noor gives us an example of a project they worked on in collaboration with the Himalayan Cultural Heritage Foundation in June 2020 to illustrate her point. The site was Chomo Phu, a small one-room Buddhist shrine near Diskit Monastery, Nubra.

“It’s quite a steep hike up from Diskit Monastery, and there is a gorge inside the valley where this shrine is located. There was no place for accommodation. Instead, we pitched tents next to the shrine and had to improvise basic facilities. We camped in that valley for about 25 days since it was not practical or possible for us to hike from there to the monastery or the village every day,” she recalls.

Before, during and after the project, Noor and her team do extensive documentation work. During this phase, they closely examine the kind of deterioration the wall painting has undergone.

In this particular case, there were a lot of over-filling and historical fills done in the past. These fills were done in such a way that it was obscuring a lot of the original painting and sometimes even overlapping it. They had to carefully remove those historic fills.

“Another issue with wall paintings is that there are a lot of detachments. In the event of any structural movement or water seepage, the plaster gets detached from the support, thus creating these hollow areas inside the painting. You can discover these hollow areas through a percussion test (a method for the structural inspection of wall paintings). We then perform grouting, i.e. fill the gaps between the painting and the support structure,” she notes.

Apart from these, there are cases where the paint layer gets delaminated. To address this, they use a consolidant and then stick the paint layer back to the surface.

“Of course, there is cleaning work which is done. The paintings are largely glue-bound tempera (also called secco, which are paintings on dry surfaces). In this kind of technique, the pigment is usually mixed with the binder and then applied to the walls. With water infiltration, the binder becomes weak causing delamination of the paint layer,” explains Noor.

“This damage primarily occurs because of water. We make sure not to perform any wet cleaning, i.e. don’t use any solvents to clean the wall painting. We only employ dry cleaning. There are various types of conservation-grade sponges which we work with and soft brushes to remove the dust or any mud infestations,” she adds.

A major point of contention with wall paintings is retouching work (reworking small areas of a painting to cover damage or to mask unwanted features).

Without getting too deep into the subject, when it comes to wall painting conservation work, Noor and her team largely stick to what she calls “conservation or stabilisation work”.

“It’s important to see your heritage as an inheritance that has great value,” says Noor Jahan

Restoring old thangkas

This year most of the thangkas that were brought in for restoration at Shesrig’s studio came from private households. Each thangka arrives in a different condition.

In thangka paintings, you have a textile-based canvas made of cotton fabric or any other material used by the artist in the centre. These thangkas also usually have either silk or brocade borders. Most thangkas they got into their studio this year had silk borders.

Step 1: “Since the thangka has come directly from the chod-khang (prayer room) to our studio, we first take it to a nearby monastery, where a de-consecration ceremony is done,” she says.

Step 2: The next step is to bring the thangka back to the studio, perform extensive documentation work including photographic documentation and understand what kind of problems are visible. Accordingly, they prepare a treatment plan.

Step 3: Usually the centrepiece of the thangka is stitched with a textile border. They separate both elements because the fabric at the border is completely different from the canvas in the centre. Following separation, they work on the border and centre piece canvas separately.

Step 4: Once the separation is done, the first step is cleaning the soot. “In thangkas, there are times (only when required), when we go for mild solvent cleaning but once again dry cleaning methods are preferred. Also, solvents can sometimes be harsh. We have started preparing gels which are much milder and do not adhere to the surface for the cleaning process,” she says.

Step 5: What if there are big losses or tears on the thangka painting? “We make a similar kind of ras-jee (the local term used for the textile canvas of a Thangka painting) in the studio. We use pieces of that ras-jee to mend the tears. Otherwise, in thangkas, we also see a lot of cracks. To fill the cracks, we use the markalak (local clay mixed with mild adhesive) to fill those cracks because that’s part of the original technique of preparing a thangka. We follow the same methods while restoring it as well,” she explains.

Step 6: Once this is done, if there is any consolidation work required or a paint layer is coming off, they fix those problems. Sometimes, they mend the tears fibre by fibre, which requires very delicate hands. Also, if there are any small losses or paint losses, they do subtle retouching work using natural colours or the colours originally used on the thangka.

Conservation of Thangsham (the local term used for the textile border of a Thangka painting)

Step 7: Meanwhile, there is another team which is working on the textile border known as thangsham locally. There is a particular method of washing the textile using conservation-grade detergents.

“We don’t dip it straight into the water. Instead, we use wet sponges to clean it very meticulously. Sometimes these borders are also torn or otherwise in a bad condition, for which we mend them using patchwork with silk, brocade or whatever material was originally used. We have a stock of raw silk, which is white. We dye it as per the thangka’s requirements. If the thangsham, for example, is blue, we will dye the silk blue and do the patchwork from the inside. We perform the process of dyeing ourselves at the studio,” she explains.

Step 8: Once both elements are ready, they stitch the centrepiece canvas and the border back together, following which a consecration ceremony is done and then returned to the client.

Once again, depending on the state in which the thangka is sent, it takes anywhere between a fortnight to two months or more to restore a thangka. It also depends on manpower.

“Most of the time, we work in groups of two or three women on one thangka, and depending on the scale of the task, it takes about a month or two if the damage is extensive,” she says.

https://www.instagram.com/p/Ci4XfdArzq3/?utm_source=ig_embed&utm_campaign=loading

‘What is this Muslim girl doing here?’

Given that most of the conservation work she does with Shesrig Ladakh relates to Buddhist heritage, questions have emanated from either side of the religious divide.

But is her faith an obstacle in this line of work?

“Most of the time, they don’t see my Muslim faith as an obstacle to the work that I do. For the most part, I’m not treated as an outsider or not from the community. In fact, it has been the opposite, where I am given more respect and love, especially in monasteries,” she says.

However, recently she heard someone say, ‘What is this Muslim girl doing here?’ “Look, this is how the world around us is moving. As Muslims in India, we know what’s going on. But I do not take these comments personally because I have to do what I know how to do,” she says.

Noor Jahan: “I have to do what I know how to do”

But such ad-hominem comments don’t necessarily come from the Buddhist community. She even notes how members of her religious community pass judgement on her line of work.

“Sometimes, people from the community approach my family to complain about my work, but fortunately they have been very understanding,” she notes.

Another struggle Noor deals with is the significant lack of awareness in Ladakh about art and heritage conservation as a field. “Even though they support me, my parents and some friends still don’t understand the kind of work I do. They still think this is a ‘hobby’ to me and don’t take me seriously. Even though the conversation in Ladakh about restoration and conservation has progressed a little, there are still people who think that this work can be done for free. This is something, I hope, changes with time as the conversation around this subject grows,” she says.

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

(Images courtesy Instagram/Shesrig Ladakh/Karamjeet Singh)

source: http://www.thebetterindia.com / The Better India / Home> Stories> Art> Heritage Preservation / by Rinchen Norbu Wangchuk / October 06th, 2022