Kolkata, WEST BENGAL :

Two remarkable women from the family of Wajid Ali Shah, the last king of Awadh, are reviving his culinary tradition in Calcutta, the city where he famously introduced potatoes into the biryani!

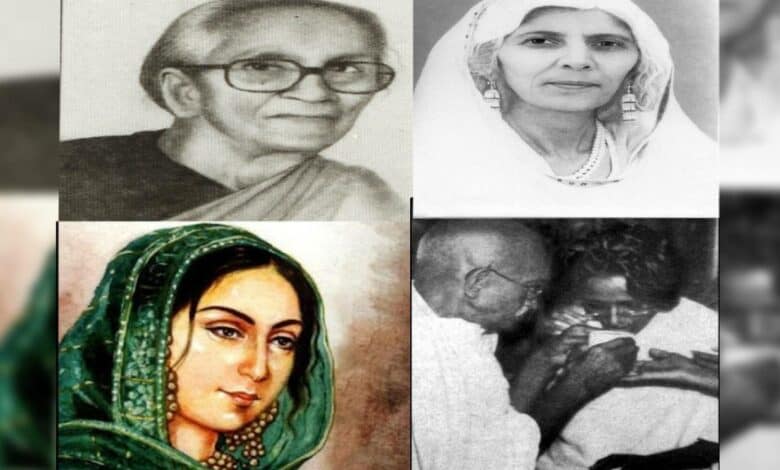

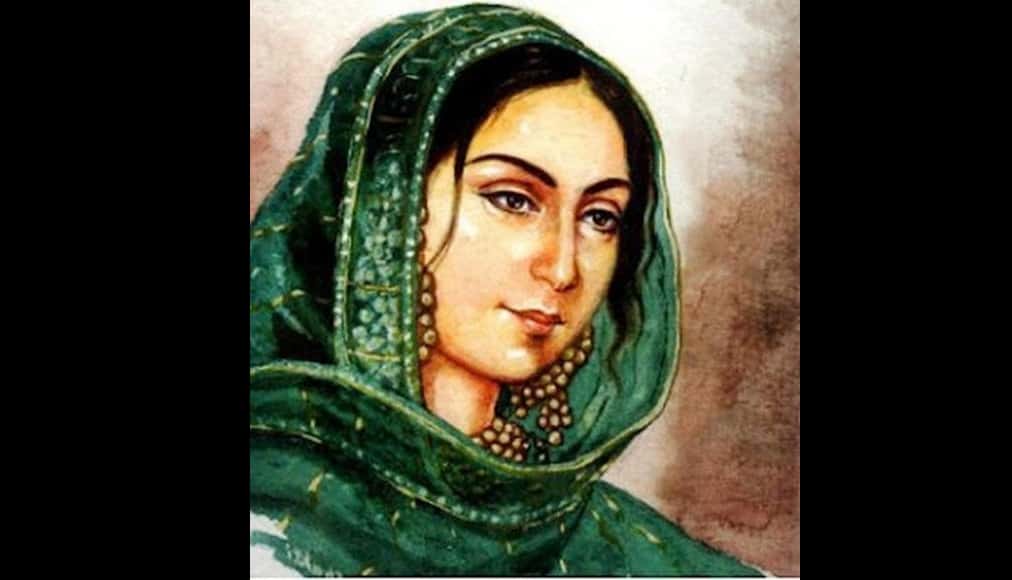

Manzilat Fatima is a descendent of Wajid Ali Shah, the last Nawab of Awadh who spent 29 years in exile in Metiayaburj, a Calcutta suburb. She launched a pop-up restaurant of Awadhi cuisine in 2014 and a home dining service, Manzilat’s, in 2018 in Calcutta. (Arijit Sen/HT Photo)

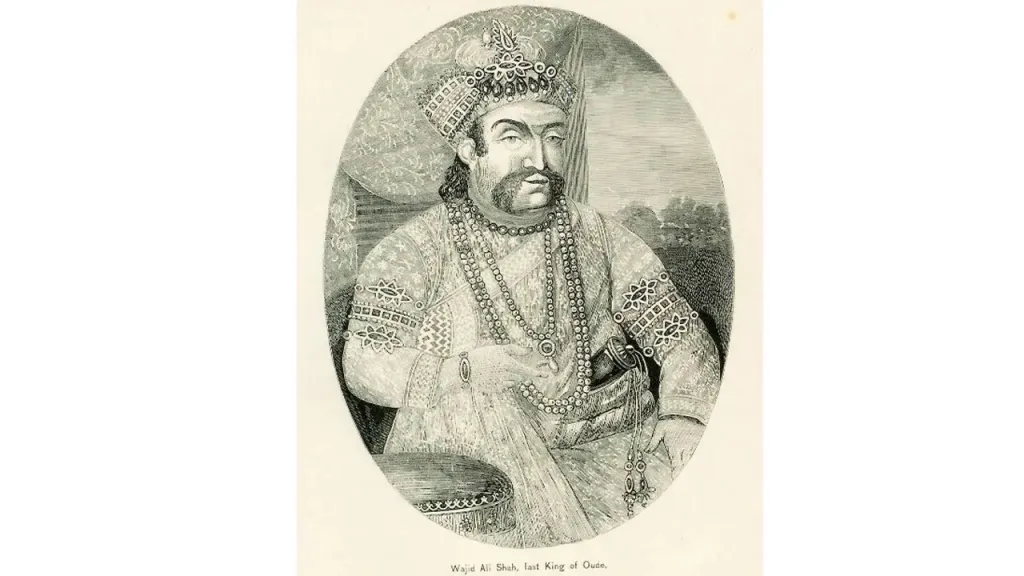

What do you do you do if a goose is plump beyond reason, won’t lay eggs and needs too much feed? Cook it, I guess. And that’s what the British Crown did to Wajid Ali Shah, the last king of Awadh, who ascended the throne as a 25-year-old in 1847 and was dethroned nine years later in 1856, a year before the first war of Indian Independence broke out.

The British said this was done because he lived and ate like a king and did little else, thus overlooking his military reforms, his attempts at administration which the East India Company did its best to thwart, and his immense popularity with his subjects.

Packed off to Metiyaburj, about four miles south of Calcutta, the ousted king was joined by his prime minister, some of his wives, musicians and officials. His chefs attended to this displaced court as best as they could. They prepared their master’s banquets with the lavishness of his days as monarch, so that when he sat for his meals, he would remember Lucknow as his great romance and not the painful reality of its passing.

If five kilogrammes of lamb mince was used to make a single kofta when he had been the king, they were not going to scale down, when he was no longer one.

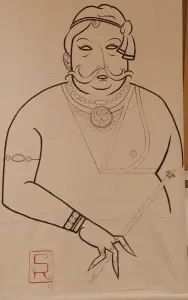

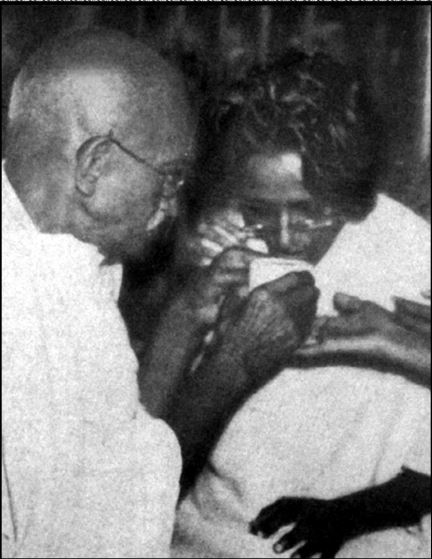

Wajid Ali shah during his days in exile in Metiyaburj, a Calcutta suburb, wearing his trademark kurta with part of his chest exposed. His descendants say it was an expression of his heart being open to his subjects. ( Arijit Sen/HT Photo )

But how do you claim, centuries later, that one of India’s most famous ex-royal is your old man and that you are the sole inheritor of the royal cuisine he helped found? Wajid Ali Shah’s descendants Manzilat Fatima, 51, and Fatima Mirza, 45, of Calcutta are doing that, courtesy the documents of political pensions of their families on the one hand, and by cooking his food, on the other. Team Manzilat and Team Fatima, both say they are the real thing.

***

Family recipes are a cook’s real estate. Wajid Ali Shah’s descendants face the problem of plenty. At the time of his death, the king had 250 wives and 42 children so no ‘family recipe’ matches the other. The British also made sure that after the king’s death in 1887, his days in exile would go undocumented.

On Fatima Mirza’s table: Kachhe Tikia ke Kebab, Mutton biryani, Nargisi Kofta. Mirza is a great-great grandchild of the last king of Awadh. ( Arijit Sen/HT Photo )

“His successors and his subjects were left with nothing,” says Wasif Hussain, the manager of the king’s mausoleum in Metiyaburj. “I’ve heard that in Chartwell House [the country home of a former British premier, Winston Churchill], his kitchen with its tea-kettle, his flour bin, the utensil rack and the weighing machine have been left intact…. It’s a museum….”

A law graduate, Manzilat Fatima, is from the ‘ruling line’. Her father, Kaukub Meerza, a former Reader of the Aligarh Muslim University, is the grandson of Birjis Qadr, the son of Begum Hazrat Mahal and Wajid Ali Shah. Birjis was crowned king by Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar during 1857 as Wajid Ali Shah was by then in Calcutta. Birjis met his death in 1893 after dinner at a relative’s home in Metiyaburj.

This was not the first time that poisoning had killed an Awadhi royal, Sudipta Mitra, author of Pearl by the River, a book on Wajid Ali Shah’s exile, points out. Royal biographies mention a consort sending the king paan as a token of her love during their better days and the king not putting it past her to lace its leaves with poison when those days were over.

The murder of Birjis and its memory have stayed with the family for over 120 years. It has seeped into Manzilat’s remembrances of her childhood home (“My paternal grandmother would always check the food before it was served to family members”), and explains her impatience with ‘proof’-seekers. Ever since she launched a pop-up restaurant of Awadhi cuisine in 2014 and a home dining service, Manzilat’s, in 2018 in Calcutta, there are some set questions she has had to answer.

“ ‘Do I have monogrammed table-mats from Wajid Ali’s time?’ ‘Did I inherit a recipe book?’ No, I didn’t! Birjis’ murder snapped our links with the other branches of the family. His wife escaped from Metiyaburj to Calcutta…. And besides, my great-great-grandmother, Hazrat Mahal, was a queen who was fighting the British, not writing cookbooks. For a while, I made this my FB status,” says Manzilat cheekily while adding finishing touches to an order of Ghutwaan Kebab (made of mashed meat marinated with papaya) that a delivery man from Swiggy is waiting for her to complete, besides the mandatory biryani.

Manzilat makes a good mutton biryani, but with mustard oil to keep it non-greasy and light; Fatima Mirza, a school principal (she is of the line of Wajid Ali Shah’s principal consort, Khas Mahal) and her husband Shahanshah Mirza (his father Wasif Mirza is another great grandson of Wajid Ali Shah) consider the leaving out of ghee an overturning of the “basic biryani rule-book”. Both families, however, have more in common than they think.

While Manzilat’s cooking displays her control in colour, sense of proportion and spicing so integral to Awadhi cooking, Fatima, too, has considerable domain knowledge. Since 2018, she has been working on a cookbook penning family recipes such as the Kachhe Tikia ke Kebab.

“This is the only Awadhi kebab in which sattu is added and it was a Wajid Ali Shah favourite,” she says. “To neutralise the heat of meat and to make it easily digestible, hakeems advised chefs to add sattu (ground Bengal gram) as the king aged. The trend seems to have been to keep things light and fragrant.”

Shahanshah Mirza, another descendant of Wajid Ali Shah, with a family heirloom – a ceramic bowl. Such bowls were common in royal households. Their contents were checked by food inspectors before they were placed before the nawab. They had a special coating which would ‘crack’ if the food had poison, says Mirza. ( Arijit Sen/HT Photo )

Shahanshah Mirza, a government official and heritage enthusiast, elaborates on the difference between Awadhi and Mughlai cuisine. “Unlike Mughlai, ours has no overdose of mace or cardamom or dry fruits. We say about Urdu, Urdu aap ke zubaan pe hamla nahin karta hai, speaking it, does no assault to your tongue… Likewise, Awadhi food plays on understatement. It is big on presentation though.” Any aspiration to cheffy-ness of the standard of the former royal house of Awadh has to get the food styling right.

Wajid Ali’s descendants also make great allowances for a master chef’s ego. It was not uncommon in the heyday of the king to have his chefs refuse to cook for any other branch of the family. Some of the chefs even announced during the time of seeking employment that they were not going to expand their expertise! That is, the maker of dal would remain a dal specialist throughout his life. A biryani cook would touch nothing else.

***

The Sibtainabad Imambara, the mausoleum of Wajid Ali Shah and his son Birjis Qadr at Metiayaburj. Birjid was declared king in the absence of his father by the sepoys during 1857 and his kingship was acknowledged by the Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar. ( Arijit Sen/HT Photo )

In Metiyaburj, Guddu, a grandson of Puttan, a descendant of one of Wajid Ali Shah’s great chefs, drops by at the Shahi Imambara, for a chat. He talks of a dish that has the sound of one made in Awadh’s hoary past. There are few “with the stomach and liver of Wajid Ali Shah” to digest dishes like a meat mutanjan (a rice dish) now, Guddu says. But Nawabi biryani, and yes, with the potato, is everywhere.

Do kings thus prepare the future food of the people? The rich trying out the pleasures that the masses will eventually grasp is something historian Fernand Braudel has elaborated upon in his works. Rows of biryani shops of various prices line the road on either side of the king’s mausoleum. “Jameson Inn, a branch of Shiraz [an old Calcutta eatery], began to make a Murgh Hazrat Mahal in 2011,” informs Hussain, the Imambara manager. But there is a piece of information doing the rounds he would like to correct.

“The potato was added to the biryani because of its exotic value. It was a new vegetable in the market introduced by the Portuguese,” says Hussain. Both Fatimas back this view. According to Abdul Halim Sharar’s Guzishta Lucknow, considered to be the go-to book for any information on Wajid Ali Shah’s exile, the king spent Rs 24,000 on a pair of silk-winged pigeons, Rs 11,000 on a pair of white peacocks and approximately Rs 9,000 a month on food for some animals in his zoo in Metiyaburj.

“If a man could afford so much, he could certainly add more meat to his biryani and not bulk it up with potatoes,” suggests Fatima Mirza. The king would presumably also not risk his social prestige. At the evening concerts in the then resplendent Sultan Khana that had all the splendour of his palaces in Lucknow, when the Calcutta elite would visit, with thumri, there was biryani and it had potatoes. Surely Wajid Ali Shah would not have a dish served that had hard times written all over it.

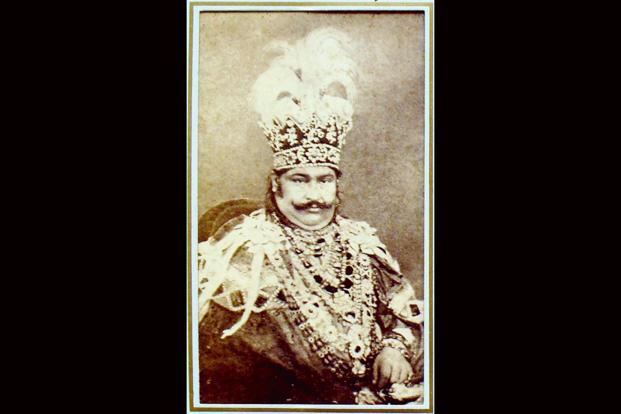

(L-R) Mohammad Sulaiman Qadr Meerza with his grandfather, Kaukab Meerza, the great grandson of Wajid Ali Shah and Begum Hazrat Mahal, and his father, Kamran Meerza. ( Arijit Sen/HT Photo )

******

Mohammad Sulaiman Qadr Meerza, 9, in a yellow tee and jeans is following the discussion on food and music, and the Awadh royal family closely. When he was six, his father Kamran (Manzilat’s brother), a businessman, disclosed his antecedents. He told his friends in between classes at school that he belonged to a royal family.

His friends asked: “Which one?” Sulaiman said he was the fifth generation of Wajid Ali Shah and Begum Hazrat Mahal. They did not believe him.

Next year, when he is 10, Sulaiman has plans to grow bigger. And then he will try to convince them. He says he must give it one last try.

Kitchen confidential- Nawabi recipes passed down the family

MANZILAT FATIMA’S PINEAPPLE MUTANJAN

INGREDIENTS

- 1 cup Gobindo Bhog rice soaked for an hour

- 1 cup sugar

- 2 cups chopped pineapples

- 2 1/4 cups boiling hot water (boiled with saffron strands and a pinch of kesariya colour)

- 1 tbspoon pure ghee

- 1 cup grated mawa

- 1 clove; 1 cardamom; almond slivers

METHOD:

Take a heavy-bottom handi, add ghee. When hot, add cloves and the cardamom, then add the whole of the drained rice and saute quickly on medium flame.

Pour the hot water in the handi. Keep the flame high for 2-3 minutes, lower the flame and keep on sim till the rice is 3/4 cooked.

In another handi, scoop out the cooked rice and make a layer; sprinkle 1/2 of the sugar and 1/2 of the chopped pineapples and 1/2 the grated mawa.

Similarly, repeat a second layer, cover the lid and keep the handi on a tawa on sim. Leave for 5-10 minutes till the sugar melts and all ingredients blend well. Switch off the gas.

Before serving lightly mix the layers, serve hot after garnishing with silver leaf and almond slivers.

FATIMA MIRZA’S KACHHE TIKIA KE KEBAB

INGREDIENTS

- Mince meat 500 gms; salt to taste

- Bengal gram flour (roasted, powdered) 2 tsp

- Garam Masala powder -1 teaspoon

- Paste of nutmeg and mace -1 tsp

- Onions -2 big ones; ginger-garlic paste -3 tsp; raw papaya paste -2 tsp

- Green chillies -2; coriander leaves

- Ghee for frying

METHOD:

Wash the minced meat. Fry the onions till they are golden brown. Mix garam masala, a paste of nutmeg, mace, fried onion and ginger-garlic paste. Sprinkle salt as desired. Add the raw papaya paste. Keep it aside for 10 minutes.

When the mutton turns tender, then mix the chopped coriander leaves and green chillies.

Using the mince mixture make flat round patties (tikia) of even size. Pour ghee into a pan. Heat it on a low flame. When the ghee crackles, start frying the patties till golden brown.

Drain out the excess ghee and serve it hot.

source: http://www.hindustantimes.com / Hindustan Times / Home> India / by Paramita Ghosh / Hindustan Times / February 24th, 2019