Rampur, UTTAR PRADESH :

Nawab Kazim Ali Khan tells the tale of the dynasty, its Raza Library, and years of progressive thinking that expanded the region and its many enterprises.

Luxury realtor Sush Clays takes us to a royal wedding in the Noor Mahal Palace, home to the Nawab of Rampur.

Nawab Kazim Ali Khan tells the tale of the dynasty, its magnificent Raza Library, and years of progressive thinking that expanded the region and its many enterprises.

His obsidian eyes halt you till you reach the twinkle in their midst. You look again, and those deep dimples flanking his wide smile reach right into your heart. And then he speaks: he tells you tales of conquering heroes and lands won and lost; princesses from far lands who made India’s sons and daughters; gemstones and swords that filled coffers; a land, united and forged as one by the many layers of the legacy of the past.

Nawab Kazim Ali Khan, much loved among his friends as Navaid bhai, is one of the most precious custodians of India’s history and some of its invaluable treasures.

Raza library in Rampur is one of the most important repositories of Indo-Islamic learning in South Asia

I met him first as Nawab Sahib, in his full reglia, when he leaned down with his statuesque Pathan grandiosity and said gently, “Call me Kazim.” I was facetiously outraged. “I love calling you ‘Nawab Sahib’,” I spluttered laughing. That didn’t last long. The bonhomie that the nawab exudes makes it hard to retain deference and address him by his title.

This was also the first of many conversations on the history of the Rampur dynasty, rewinding its track through accession and succession, the British Raj and India’s Independence, right back to the Marathas and the Mughals.

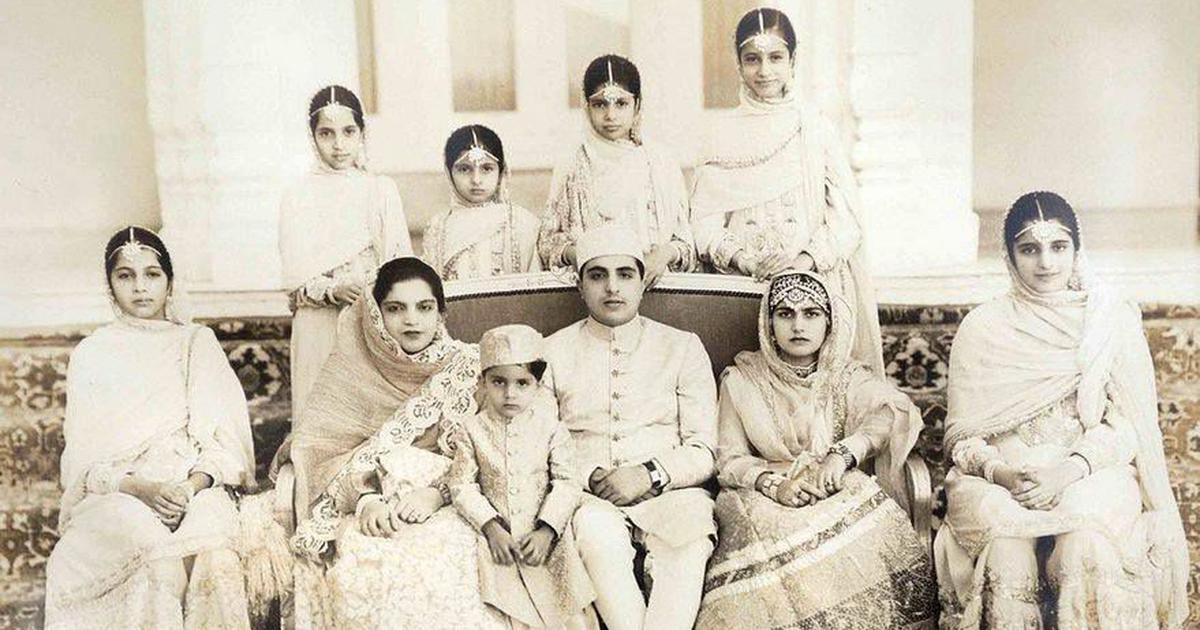

The Rampur royal family bedecked in heirlooms at the wedding

The Rampur state was created by the Rohila Afghan Pathans of Kandahar. The Yusufzai clan were originally traders. Their leader had two sons, Dawood and Kaisaf Khan. This was when the Marathas, a Hindu warrior sect, were fighting back the Mughal dynasty in the subcontinent. They had reached up to what is now northern Uttar Pradesh in victory.

By the 1700s, the Mughals engaged the services of the Pathans and the first battle pitted the Marathas against the Pathans in Fatehganj. The Maratha Peshwas were defeated and pushed down to Gwalior. In honour of this victory, the Mughals gave the Pathans eight districts in Rohilkhand. Dawood Khan moved to India, and this marked the beginning of the Rohila family saga in India. Faizullah Khan, one of the eight grandsons of Dawood Khan, inherited the kingdom of Rampur and was established as its first nawab.

The drawing room in Noor Mahal

During the British Raj, as the city of Rampur expanded, a new undertaking of building the Khas Bagh palace was begun. Built over several years and completed in 1930, it marries a variety of architectural styles. With India’s Independence came a new strain of history into the Rampur family. Nawab Raza Ali Khan was the first to merge his state into the Indian Union in May 1949.

The Raza Library is ensconed in acres of manicured gardens

And finally, in 1960, Noor Mahal, formerly the Viceroy’s representative’s palace, was turned into a haveli—as it stands now—for the birth of Nawab Kazim Ali Khan. He grew up there surrounded by his governess and staff, was fed food cooked in copper vessels, and had a daily appointment between 6 pm and 8 pm with his grandfather in Khas Bagh.

Noor Mahal, where Navaid bhai lives to this day, stands surrounded by his lush never-ending acres of farmland. The haveli holds priceless treasures: intricate vases, jade pieces of pottery, and photographs of the family beautifully installed by Queen Mother Begum Noor Bano and the current queen of Rampur, Begum Yaseen Ali Khan. Built in the classic British Raj style of architecture, with open verandahs circling the palace, Noor Mahal is where the heart of the family resides.

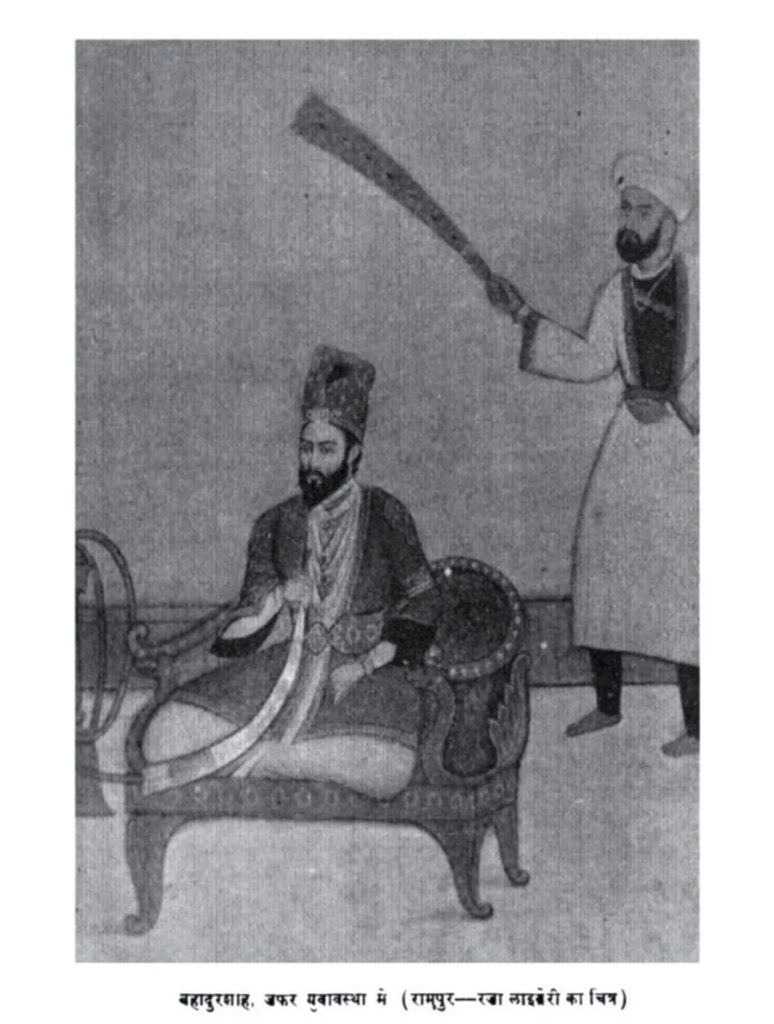

A painting of Bahadur Shah Zafar from the collection of the library

The Raza Library is the crown jewel of the Rampur dynasty. It stands tall and imposing, a precursor to the Indo-Saracenic architectural style, ensconced in acres of manicured gardens. The erudite Rampur nawabs had a passion for learning and collected over 22,000 manuscripts since the library was established in 1774 by Nawab Faizullah Khan.

They were also great promoters of women’s education. Begum Noor Bano, a descendant of Uzbekistan royalty, brought several manuscripts to Rampur as her bridal gift to the family. Today, the Raza Library remains one of the most important repositories of Indo-Islamic learning in South Asia. Its range of manuscripts stretches from Persian to Arabic, Pashto, Sanskrit, and Urdu. The collection includes the al-Qurani Majid, a priceless manuscript dating to the seventh century AD, and an illustrated Ramayana translated to Persian around 1715 AD.

Navaid bhai takes his daughter-in-law on a tour of the treasures of Rampur

Firm believers in the value of secularism and progressive thinking, the Rampur Nawabs were the only Islamic kingdom where the coronation ceremony was performed by a Hindu Brahmin pandit. With the advent of industrialisation, the far-sighted rulers realised that agriculture alone could not sustain the economy. Hence, the land was leased out to several manufacturers, including a distillery that produces the fabulous Rampur Single Malt Whisky today. With the birth of democracy in India, the instinct of the sovereign ruler of the time was to enter politics or the armed forces. Navaid bhai’s grandfather, Nawab Raza Ali Khan, was the honorary colonel of two infantries and an armoured regiment that participated in World War II to protect what was to become Indian territory post Independence.

Nawabzada Haider Ali Khan and his bride Shaukat Zamani Begum

Queen Mother Begum Noor Bano was the first female member of the family to successfully contest elections and win the seat of Rampur. This began a new era in the lives of the Rampur family. The seat of the nawabs was then moved to Noor Mahal so that they could move a little away from the swiftly expanding city of Rampur. This brings us to the present day when I find myself at this stunningly historic haveli to celebrate the wedding of Nawab Kazim Ali Khan’s second son.

The wedding portrait of Nawab Kazim Ali Khan and Begum Yaseen Ali Khan

The year 2020, with all its woes, brought this one joyous occasion for Navaid bhai to gather an intimate group of family and friends and celebrate the nikah of his second son, Haider Ali Khan, to the beautiful Shaukat Zamani Begum. Sufi music composed by Navaid bhai’s grandfather fills the haveli. An incredible performance of a whirling Sufi dancer puts us in a delicious trance. The exotic aroma of Rampur’s extraordinary cuisine titillates our olfactory nerves. And the melting flavours of the famous chapli kebab make our palates spiral into ecstasy. As our senses are soothed into sublime languor through three days of feasting, dancing, laughter, and love, we awake to the nikah on the final morning.

The pure pageantry of the ceremony is a joy to behold. Begum Zamani is clad in an intricately embroidered sharara that requires three bridesmaids to carry it; Nawabzada Haider is dressed up in his Pathan grandeur, with the family’s bejewelled heirloom sword; Navaid bhai is in a stunning rose ensemble and Begum Yaseen in delicate beige—the scene belongs to a different time, a few thousand years before 2020.

The dynasty is inclusive as always, and the rites are performed in Shia and Sunni traditions. And then the gentle, lilting sound of “Qubool hai” from the bride’s veil confirms her assent to the marriage to Nawabzada Haider, sending the guests into raptures.

The Pathani nawabs of Rampur have always adopted the Hindu rituals of their homeland, so they include a henna ceremony and an evening of dancing to celebrate the union.

Begum Zamani clad in intricately embroidered sharara for her nikah

The ceremony verifies everything the nawab has told me about his family, “Of the 300-odd sovereign states of the Union of modern India, there are only a dozen Islamic royal families. Ours has always believed in educating our women, and we have forever held a deep passion for art, literature, and music.” Rampur sparkles as a shining example of myriad traditions evolved into a singular culture, which spans thousands of years and retains a resplendence of its own in modern India.

The writer is the founding partner of Welcome Home Luxury Real Estate Services in New Delhi.

source: http://www.travelandleisureasia.com / Travel and Leisure / Home> Hotels / by Sush Clays / January 20th, 2021