BENGAL :

Mir Qasim Ali Khan Bahadur was the Nawab of Bengal between 1760 and 1763. He is most famous for his dealings with the British: he was put on the throne through the intervention of the East India Company, but a few years later was defeated by their forces at the Battle of Buxar. This defeat marked the decline of the political power of the Nawabs of Bengal and was an important moment in East India Company imperial consolidation in Bengal.

All of this is important, of course, but I’m here to discuss a far more pressing question: what did the Nawab and his contemporaries eat?

I encountered this manuscript, titled Khwan-e Nimat, “The Beneficent Table,” at the library of Jamia Millia Islamia here in Delhi. Composed in Persian, the text promises its readers a description of “the art of cooking from the private kitchen of the chef of Nawab Qasim Ali Khan Bahadur.”

The text describes how the Nawab’s chef prepared fish kabab with rice, several types of meat kababs, fried eggs, sweets made with almonds, a few different types of pickles, pulao, khichri, qorma, various dals, mango jam, sheermal (a sweet bread), and on and on.

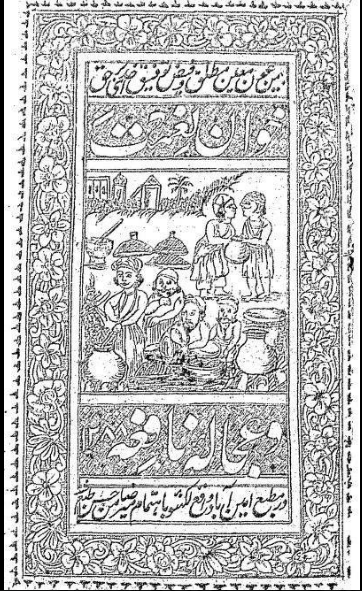

Although I originally encountered this work in manuscript form at Jamia, after some hunting I discovered that a lithographed version was printed in 1871 in Lucknow.

The printing was done by a small press, but it means that there was at least some awareness of and interest in the text in the late nineteenth century, a century after the political power of the Nawabs of Bengal had waned. As such, it offers us insight into not only the culinary preferences of Mir Qasim and his court, but also the culinary interests and understanding of food history among North Indians in the high colonial era.

Over the course of my research I’ve stumbled on several cookbooks written in Persian and Urdu over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth century, but I’ve found there is very little written on colonial-era traditions of writing about food in these languages. Many of the Indian food histories written on this period focus on the British adaptations of Indian cuisine, and exchanges between British and Indian cooks and palates. This text and its later publication tell an alternative (and I’d argue more interesting!) story: that of Indian interest in various local cuisines, and the desire of members of broader literate classes to know and perhaps try to prepare cuisines cooked by regional elites and leaders.

I’m craving fish today, so here’s a rough translation of how the Nawab’s chef prepared his fish kabab. Following these recipes is a bit of a challenge because most of the units of measurement appear to be regionally or temporally specific, and have changed significantly; many are not in any of the Urdu or Persian dictionaries I’ve consulted. I’ve therefore taken educated guesses based in large part on what I know about cooking, and the limited information I could find on the units used.

Ingredients:

Fish (type not specified, perhaps about 650 grams)

Butter (possibly referring to ghee; approximately 80 grams)

Onion (perhaps two-three)

Curd (approximately 15 grams)

Malai (approximately 20 grams)

Coriander (approximately 20 grams)

Black pepper (approximately 15 grams)

Gram (Chickpea) Flour (approximately 60 grams)

Pepper (mirch, presumably red?) (approximately 20 grams)

Cloves

ٓA pinch of lemon juice

A pinch of cardamom

Several pinches of salt

Cut the fish into chunks in the size of kababs and place them aside. Prepare the gram flour well (toast it?). After that, mix it together with the salt, pepper, crushed coriander, and some of the butter. Mix this into each kabab. Then finely chop up the onions, and fry them in some butter and then also mix the onions with some butter into the kababs. Then mix the lemon juice, cloves, and cardamom together. Drain the curd of water and strain the malai, and coat the kababs with these things. Then place these kababs in pot with the (cooked?) rice, and take the remaining spices and sprinkle them into with the rice and kababs. Roast/fry (prepare over a hot surface) and enjoy!

source: http://www.archivaldistractions.wordpress.com / Archival Distraction / by Amanda Lanzillo / July 07th, 2018