Patna, BIHAR :

Cemeteries representing Patna’s chronicle of history and heritage are dying a slow death

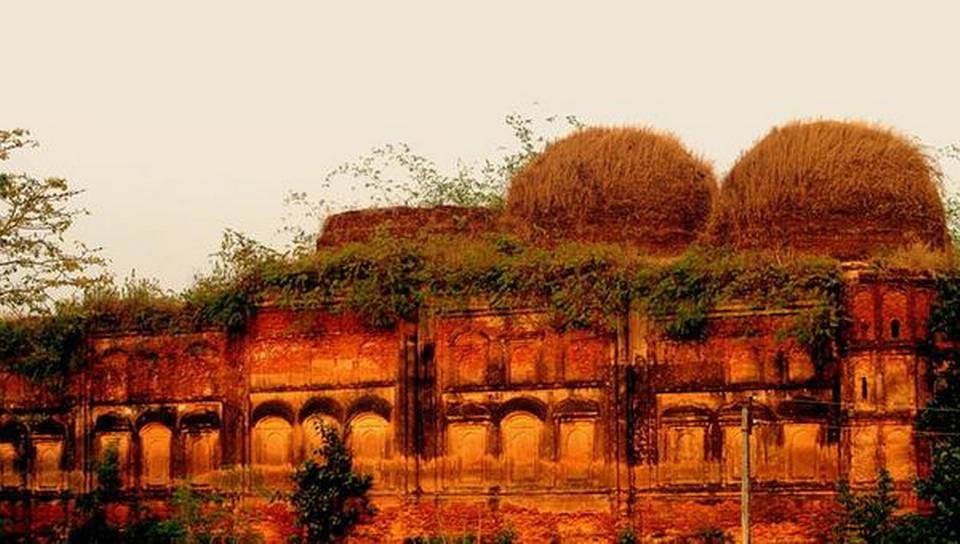

Unkept Legacy: The grave of Shahzada Karim Shah, the great-grandson of Tipu Sultan.

Like every other city, Patna also owes, to an extent, its cultural and literary existence to the courtesans who blended with the local society and provided it with a new dimension. One among them was Allah Jilai, who had settled in Patna from Allahabad. She was considered a gorgeous woman and sported a honey-dipped voice which had an arresting power. While visiting Calcutta, she developed a terminal illness. She was barely 24 when she died in 1918 and was buried in the Pakki Dargah Muslim graveyard. Her tombstone with 12 lines of Urdu couplets helped in figuring out her biographical information. Had there been no tombstone one would have never known her existence in Patna and the services that she rendered to the city.

Patna, other than being the capital of Bihar, served as a home to multiple cultures, identities, art forms and families. Today, the city has almost lost the reminders of its glorious past. But a few graves still stand as reminiscent of a bygone era. These tombs, or time capsules, where hundreds of stories remain buried, are largely deserted, ignored and unknown.

Bihar is home to more than 9,272 graveyards, according to the government’s estimate. The Bihar government planned to fence these cemeteries, and in 2022-2023, a total of Rs 93.74 crore was approved for this purpose, while an additional amount of Rs 1.25 crore was set aside for the same. According to Bihar Finance Minister Vijay Kumar Chaudhary, the fencing of about 7,647 graveyards has been completed, and the remaining will be done shortly.

In addition to the 9,272 cemeteries, Bihar also has a sizable number of privately-owned graveyards maintained by the families of former nobles, aristocrats, zamindars, jagirdars and nawabs. Thus, the overall number of burial grounds in Bihar would be close to 10,000. Moreover, several Christian cemeteries are located in Patna.

Further east on Ashok Rajpath, one can find the Gurhatta cemetery which chronicles the gruesome massacre of the British prisoners at the house of Haji Ahmad Ali in 1763 at the command of Mir Qasim, the nawab of Bengal.

The tomb of Mir Mohammad Naseer, the father of the first Nawab of Awadh Photo: Ali Fraz Rezvi

Padri Ki Haveli is the final resting place of people from Armenia, Portugal, France, Persia, Italy and the UK. In a sense, this place is a symbol of international harmony. Here, one can find a Jewish grave next to a Chinese, and a Greenlander adjacent to a Mozambican.

Near Patna Ghat Railway Station is the Danish Kothi—established in 1775—signifying the presence of Denmark in Patna in the past. It was the house of Jorgen Hendrich Berner (1735-1790), Chief of the Danish Factory in Patna, who was buried on the premises as demonstrated by his tombstone. There are at least three more tombs here which are bereft of inscriptions. Later, the Kothi became the residence of the station master of Patna Ghat, and is at present, the office of the store in-charge of railway electrification.

The Lost Glamour

While Zohra Bai, the queen of thumri, remains buried within the campus of Rauza Masjid at Maharaj Ganj, Haider Jaan, Najban, Ramzu, and Chhottan were also the tawaifs (courtesans) whose presence had made Patna a lively place.

These courtesans participated in religious activities as well, and the existence of the Imambara at Chowk is a living example of their dedication towards such pious endeavours.

As we move towards the eastern corner of the city, another story lies buried in the deadlands of Begumpur.

Father of a Persecuted Son

Popularly known as Nawab Shaheed Ka Maqbara among the locals, is the tomb of Ihteram-ud-Daula Nawab Zain-ud-Deen Ahmad Khan Bahadur Haibat Jung, the father of Nawab Siraj-ud-Daula of Bengal. Nawab Haibat Jung successfully defended Patna during the Maratha attacks but was later murdered by the Afghan rebels. His wife and children were imprisoned when he was killed.

The tomb of this martyr lies deserted in Begumpur, guarded by Dashrath Gope Yadav who comes at dawn and leaves by dusk. “The tomb, mosque and the several acres of land belong to the State Waqf Board which is least interested in the property unless there’s a chance to sell,” says Dashrath, as he cleans the interiors of the tomb. The place also had an Imambara which used to host majlises during the month of Muharram in the presence of Raja Ram Narain, the then deputy governor of Bihar.

Padri Ki Haveli is the final resting place of people from Armenia, Portugal, France, Persia, italy and the UK. it is a symbol of international harmony.

Dashrath has devoted 45 years of his life to this tomb of Nawab Shaheed. “This place had a dense jungle and I cleared it all on my own. No one from the Waqf Board or the caretakers helped me. There was no roof at this tomb, so I went around begging in the streets of Patna so that there could be a roof at the grave,” he says.

Affectionately, he calls Nawab Haibat Jung as Data Sahib—a term usually used for Sufis. Dashrath believes that he is at peace and his children are married because of the blessings of Nawab Haibat Jung.

This is not the only case of a burial place turning into a mazar. While he is aware of Nawab Haibat Jung and the history, another tomb in the city’s centre has been converted into a Sufi shrine by the people unaware of the person buried inside.

Nawab Munir-ud-Daula Raza Quli Khan Bahadur Nadir Jung, a minister of Mughal emperor Shah Alam, was the founder of the Patna Bhiknapahari and Bhagalpuri families. He was instrumental in obtaining a grant from the emperor for the East India Company and assisting the reappointment of Shuja-ud-Daula to the Vizarat. He remained in charge of Korah and Allahabad until a little before his death in Benares on October 11, 1773. Later, his corpse was transported to Patna, where he was laid to rest.

His tomb, embracing a Persian inscription of eight lines, is located west of the Government Hospital in Patna. The vicinity is collectively known as Bawli. The grave is located on a raised platform of about four feet from the ground level and enclosed by intricate lattice designs of stone.

Surprisingly, his grave has lately attained the status of a Sufi shrine where devotees of all faiths converge to venerate him. His followers used to organise a majlis (a religious discourse to commemorate the martyrdom of Imam Hussan, the grandson of Prophet Mohammad) at his shrine during Muharram. It is imperative to observe how the mausoleum of an astute politician is providing spiritual respite to everyone and is acting as a melting pot of different cultural, religious and ethnic affiliations, thereby bridging the communal and sectarian divides.

The Awadh Connection

Mir Mohammad Naseer Nishapuri was the father of the first Nawab of Awadh, Mir Mohammad Amin. Being a descendant of the Seventh Shiite Imam, Musa Kazim—a progeny of Prophet Mohammad—he was considered among the nobles. He along with his eldest son, Mir Mohammad Baqar, reached India in the reign of Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah and settled in Patna, where he was provided with subsistence allowance by Murshid Quli Khan, the governor of Bengal, at the recommendation of his son-in-law, Shuja Khan, who also had his roots in Persia.

When his son, also named Mir Mohammad Amin (Saadat Khan Burhan-ul-Mulk), came to Patna in 1708-09, his father had already passed away and was buried in a cemetery. Subsequently, both brothers, Mir Mohammad Amin and Mohammad Baqar, in search of employment, set out for Delhi in the beginning of 1709.

The tomb of Nishapuri is located to the north of Patna City Railway Station. It borders the Kachchhi Bagh Cemetery and the nearest landmark is the now-defunct Pradeep Lamp Factory. It lies in a roofless rectangular enclosure, supported by ornamental arches and turrets of small heights. There are remains of flower motifs on the walls. The intricate stone lattice work on the arches has disappeared and the horizontal beams supporting the enclosure have also fallen at places due to the absence of proper maintenance. There is a garage in the vicinity which is using the site as its dumping ground, thereby causing further damage to it. Moreover, the overgrowth of trees and shrubs is also playing its notorious role to damage the place. This neglected heritage, which should have been a symbol of Patna’s glorious past and its royal association with Awadh, is counting its final days.

Several tombs are scattered across the city of Patna; some are fortunate to bear a name or a tombstone while the others remain deserted and ignored.

When Safdar Jung visited Patna in 1742 to support Ali Vardi Khan to push the Marathas out, he paid a visit to the grave of his maternal ancestor and recited the Quranic verses or Fatiha to his soul. It was at his instance the walled enclosure and latched screen (carved jaalis) were built around the burial place.

The aforesaid site had an attached Imambara where Muharram majlis were held, but nothing remains now. The disappearance of such heritage is swiftly obliterating the past of the city and disconnecting the cultural thread which joins several eras.

The Prince of Mysore

Among all the legendary personalities buried in the city, there exists a chapter of Mysore’s history in an unimaginable grave at Meetanghat, Patna. In the compound of Khanqah Bargah-e-Ishq Takiya Shareef—where rests the great Sufi mystic and poet of the 18th century, Shah Rukn-ud-Din Ishq Azimabadi—exists the burial place of Shahzada Karim Shah, the great-grandson of Tipu Sultan.

He was a man of mystic inclination and was thus affiliated to the Khanqah of Hazrat Ishq Azimabadi, through his pir, Syed Shah Khwaja Amjad Hussain Saheb. He died in Patna in 1915, and Shamshad, a poet, composed a Persian inscription of 10 lines for his tombstone.

He was a man of mystic inclination and was thus affiliated to the Khanqah of Hazrat Ishq Azimabadi, through his pir, Syed Shah Khwaja Amjad Hussain Saheb. He died in Patna in 1915, and Shamshad, a poet, composed a Persian inscription of 10 lines for his tombstone.

There exists as a cemetery of history in Bihar—the grave of Shahzada Mirza Zubair-ud-Deen Bahadur Gorgani, the grandson of the last Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar, at Darbhanga or the tomb of Yusuf Shah Chak, the Sultan of Kashmir who reigned from 1578 to 1586, and was exiled by the Mughal Emperor Akbar. He along with his family members now rest in Biswak, Nalanda. Furthermore, Mahmud Shah, the fourth king of the Hussain Shahi dynasty of Bengal, died in 1538 AD in Kahalgaon (previously spelled Colgong), Bhagalpur, and was buried there. Similarly, Hussain Shah, the last king of the Sharqi dynasty of Jaunpur, took refuge at Kahalgaon and died there, and Sher Shah Suri, the founder of the Sur dynasty, lies buried in Sasaram. Sadly, Bihar’s Chief Minister Nitish Kumar is busy presenting a model of development upon the ruins of Patna’s heritage, while these graves representing the chronicle of history are dying a slow death.

Syed Faizan Raza is the area representative of the British Association For Cemeteries In South Asia

Ali Fraz Rezvi is an independent journalist, theatre artist and a student of preventive conservation

source: http://www.outlookindia.com / Outlook / Home> National / by Syed Faizan Raza and Ali Fraz Rizvi / Novmber 04th, 2023