TAMIL NADU :

Nuskha-e-Shahjahani, published by the government under its Oriental Series in 1956, hopes to make readers “eat with their eyes” as there are no photographs in the book to illustrate the dishes. It contains recipes for ‘pulao’, roast meats, pottage and omelettes, puff pastry savouries, sweetmeats, and yogurts.

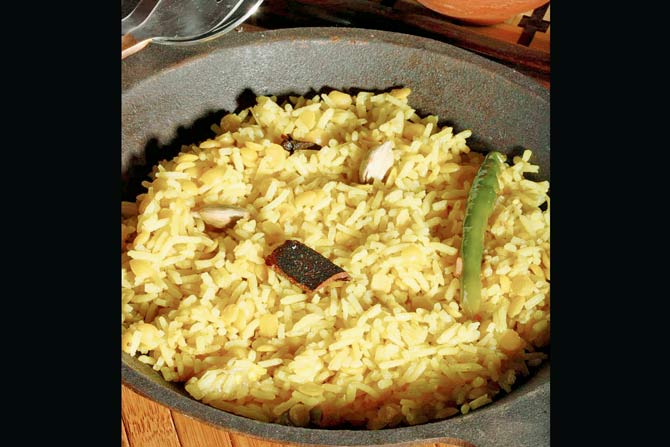

The unnamed author describes 56 ways of preparing ‘pulao’ in Nuskha-e-Shahjahani. | Photo Credit: Ruth Dhanaraj

Any mention of the Mughal empire would not be complete without a reference to its rich cuisines. It is interesting to note that as early as 1956, the Government of Madras had brought out a Persian compilation of recipes from the royal kitchen of Mughal Emperor Shahjahan.

Nuskha-e-Shahjahani, published by the government under its Oriental Series, is a cookbook that hopes to make readers “eat with their eyes”, though there are no photographs to illustrate the dishes. The compendium relies on word power to conjure up images of what may have transpired as expert cooks went about creating repasts fit for a king.

Nuskha-e-Shahjahani is based on two source materials. The first is a single Persian paper manuscript described under No. D.596, containing 186 pages with 11 to 14 lines on a page, dated 1263 A. H., from the Government Oriental Manuscripts Library in Madras. The other is from the India Office Library in London, which is incomplete, with nine sections that are written in the Shikista (a ‘broken’ version of the nasta’liq calligraphic script), and titled Nan-O-Namak (Bread and Salt).

Its 10 sections contain detailed recipes for ‘pulao’ (rice and meat dishes), roast meats, pottage and omelettes, puff pastry savouries, sweetmeats, and yogurts. Colouring of food and oil, with natural methods, besides the preparations of jams and condiments from fresh fruit, all find a mention in Nuskha-e-Shahjahani.

The unnamed author is a man familiar with culinary arts. He describes 56 ways of preparing ‘pulao’ and 36 recipes for ‘Qaliah’, a flavourful thin curry.

Love of display

In his introduction to the 1956 volume, editor Syed Muhammad Fazlullah writes, “Shahjahan is considered to be a lover of display in all matters compared to the other Mughal emperors. His reign was a period of peace and plenty… His table was very extensive and displayed a variety of rich dishes. The high degree of excellence of the royal kitchen can be imagined from the study of Nuskha-e-Shahjahani.”

The Mughals were known to pay considerable attention to their food and its presentation. Emperor Akbar, for instance, appointed experienced men to look after the cooking, and also devised rules for the conduct of the royal kitchen, which was administered by the Prime Minister. The officer-in-charge was called ‘Mir Bakaul’, who would oversee the work of subordinate expert cooks appointed from different countries. A separate budget was maintained for the kitchens.

Written down by scribes

“After translating a collection of ‘pulao’ recipes in 2007 from Nuskha-e-Shahjahani, I realised that there may be other manuscripts related to recipes from the Mughal era,” Gurgaon-based food historian and author Salma Yusuf Husain told The Hindu. The Persian language scholar’s English translation of Nuskha-e-Shahjahani was published in 2019 as The Mughal Feast: Recipes from the Kitchen of Emperor Shah Jahan.

Ms. Husain’s search led her to noted libraries and museums in India and abroad. “Most of the recipes were written down by the official scribe known as ‘Munshi’. Besides Nuskha-e-Shahjahani, Ain-al-Akbari, Alwan-e-Nemat and Nimatnama-i-Nasiruddin-Shahi are among the handful of food-related manuscripts from this era,” she said.

The Nawabs of Awadh followed the Mughals by opting for elaborate menus. Editor Fazlullah mentions that the food expenditure in the kitchen of Nawab Shujauddaulah came up to ₹7 lakh per year, apart from the salaries of the cooks and other staff. It is said that Nawab Salarjung’s cook earned ₹1,200 per month.

But what passes for Mughal food is just an Indianised version of the original, said Ms. Husain. “The Mughals used only three to four spices, such as cumin, coriander, and saffron, besides a variety of dry fruits in their dishes, so their dishes would have been bland. The Portuguese brought chillies to the Indian platter during the latter half of Shahjahan’s reign. Mughal food in India today tastes more of spicy gravies cooked in oil rather than the base ingredient,” she said.

Though the taste profile may have changed, some techniques have lingered. The Mughals had a penchant for slow cooking and grilling, allowing ingredients to stew in their own juices.

“‘Zer biryan’ was a technique where wooden sticks would be laid out on the base of the pan, and marinated meat would be placed on top. The pot would be heated slowly and the meat would cook without coming into contact with the vessel. When half-done, par-boiled rice would be spread over the meat, and the vessel would be sealed and cooked on dum (heat compress),” said Ms. Husain. Contrary to perception, vegetarian recipes were plentiful. Dishes like ‘navratan pulao’ and ‘pulao-e-anardana’ (made with pomegranate seeds) and gravies with chickpeas were commonly prepared.

Government initiative

Nuskha-e-Shahjahani was among the many rare manuscripts to be taken up for publication by the Government of Madras from early 1948. Lists were made from the collections of Sarasvati Mahal Library in Thanjavur and the Government Oriental Manuscripts Library in Madras and publication was overseen by expert committees drawn from the academia of the time.

The Madras Government Oriental Series published rare manuscripts in Tamil, Sanskrit, Telugu, Malayalam, Kannada, Persian, and Arabic from the Madras institution, while those in Tamil, Telugu, Marathi, and Sanskrit were selected from the Sarasvati Mahal Library. In a world where food is integral to televised entertainment, with nearly everyone a ‘master chef’, thanks to social media, Nuskha-e-Shahjahani harks back to a time when cooking was as much an art as a science.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> News> India> Tamil Nadu / by Nahla Nainar / January 24th, 2024