DELHI :

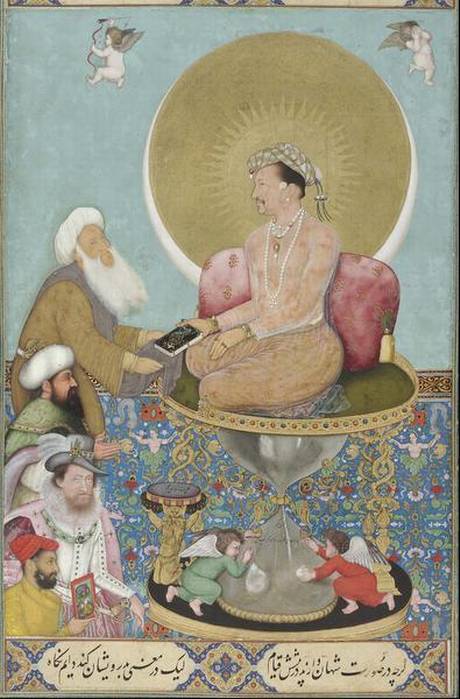

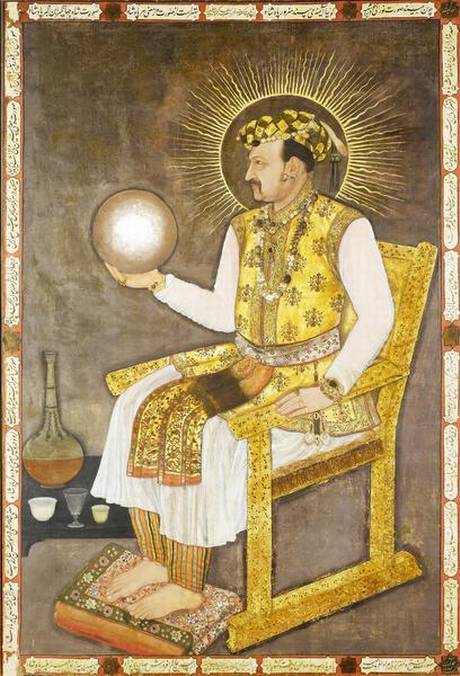

Emperor Jahangir’s inquisitive mind is revealed in his conversations with Mutribi al-Asamm Samarqandi

The 18 decades of the Great Mughals (1526-1707) produced some first-rate literature.

Many fine books came from the rulers themselves, steeped in a tradition of high culture that required them to be literate. The Baburnama, the first memoir/ autobiography of the subcontinent, is as readable today and as modestly written as Julius Caesar’s books (Cicero said of Caesar’s prose that it is unadorned, like a classical statue). The Tuzuk of Jahangir is filled with bombast, vanity and anger, but it is so honest and has so much detail, particularly on the side of his interests as a naturalist, that it is a work of the highest order.

And then there are the works that are smaller but sparkling, like little jewels. One such is the life of Humayun by his sister, Babur’s daughter and Akbar’s aunt, Gulbadan Begum. Written in Persian, as opposed to the Chagatai Turk that Babur wrote in, it is clear and direct, and as thorough a portrayal of Babur and Humayun as what they produced themselves. The story we know of Babur circumambulating the bed of a very ill Humayun and asking, in pagan fashion, to be taken instead of him, is from her book.

Courtly manners

The work we are looking at this time is from a lesser noble, a traveller from Samarqand called Mutribi al-Asamm, who spent time in Jahangir’s court. It is available in translation as Conversations with Emperor Jahangir. The Mughals loved having people over from their ancestral lands, which they would never see again, and lavished them with gifts and honours. Mutribi came to India (Jahangir was based in Lahore) roughly 400 years ago in 1627, when he was 70 and the emperor 58, only a few months away from his death.

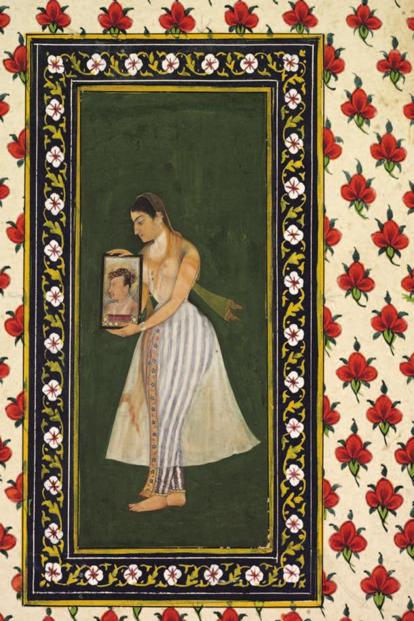

Mutribi’s writing reveals a lot about the flowery manner of the court. He visits Jahangir a month after arriving in India and the emperor asks why he has waited this long. Mutribi refers to himself in the text as the “incompetent narrator” and Jahangir as possessing “a tongue of pearls”. At that first meeting, Jahangir gives him a thousand rupees and Noor Jahan (“may her chastity be preserved”) another five hundred, possibly the equivalent of crores in our time.

At their next meeting, Jahangir inquires about the hue of the black stone from which his ancestor Timur’s sepulchre is made in Samarqand. The emperor produces stones which Mutribi compares unfavourably to the original (“it is so bright you can see your face in it”).

Lord bountiful

The transactional manner of the exchanges is apparent from another meeting in which Jahangir asks Mutribi which of the Iraqi thoroughbred horses on display he would like to be given. Mutribi says, “whichever is more expensive,” possibly to make the emperor feel that he is being generous rather than his supplicant greedy. Again, when Jahangir offers him a choice of saddle — velvet or broadcloth — the answer is velvet, because it is more expensive. Jahangir says velvet gets wet easily, to which Mutribi says that the monsoon is far off. The two meet 24 times in two months before Mutribi returns. Towards the end, the following conversation is held:

“The pleasantness of Samarqand was being discussed. The Emperor asked me, ‘Is Samarqand spelled with a ‘q’ or with a ‘k’?’

‘Either way is correct,’ I replied. ‘In Tabari’s history and several other books it is referred to as Samarkand, but in popular usage it has become known as Samarqand. Some say that the name comes from Samar and Qamar, two slaves of Alexander the Great who built the city which was then named for them. Their graves are situated in the main market square of Samarqand.”’

Then Jahangir inquires about an ancestral tomb, asking how much it requires to be maintained. ‘“If you want to do it properly, 10,000 rupees,’ I [Mutribi] said, ‘otherwise 5,000 rupees just to keep it going.’

‘If 10,000 rupees will maintain it,’ he said, ‘then we have decided that in accordance with your information we will send 10,000 rupees, in order that that blessed station be maintained.’

I said, ‘O God, as long as the Sun and the Moon shall be, may Jahangir son of Akbar remain King.’”

Aakar Patel is a columnist and translator of Urdu and Gujarati non-fiction works.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Books / by Aakar Patel / November 13th, 2021