INDIA:

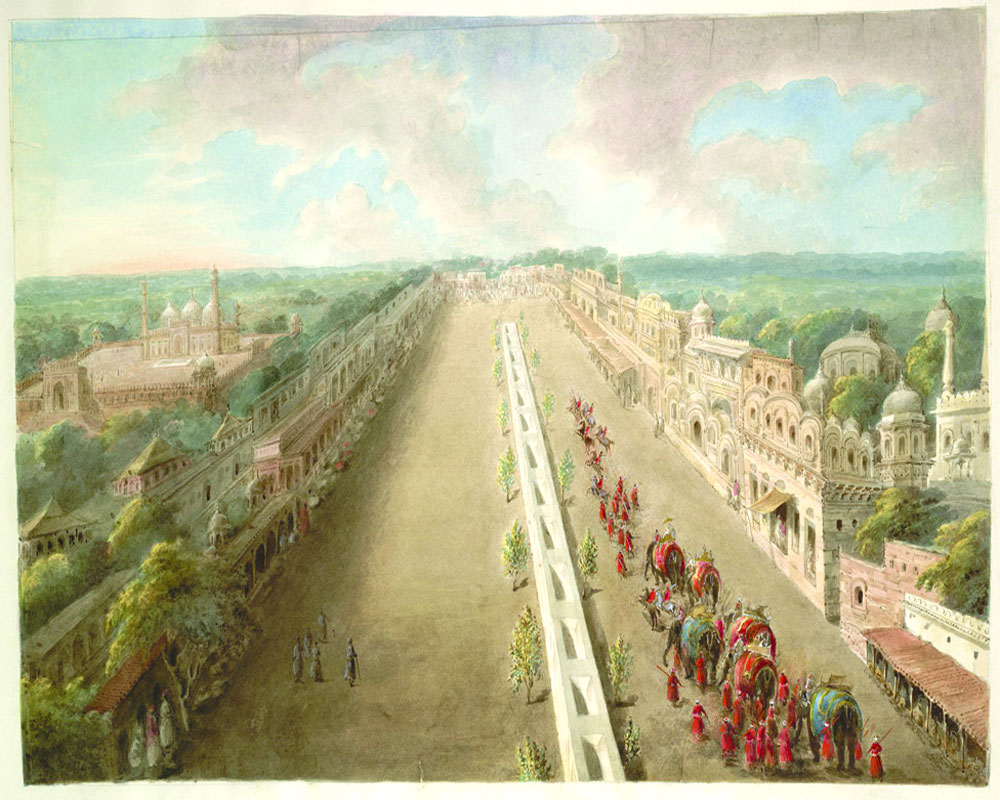

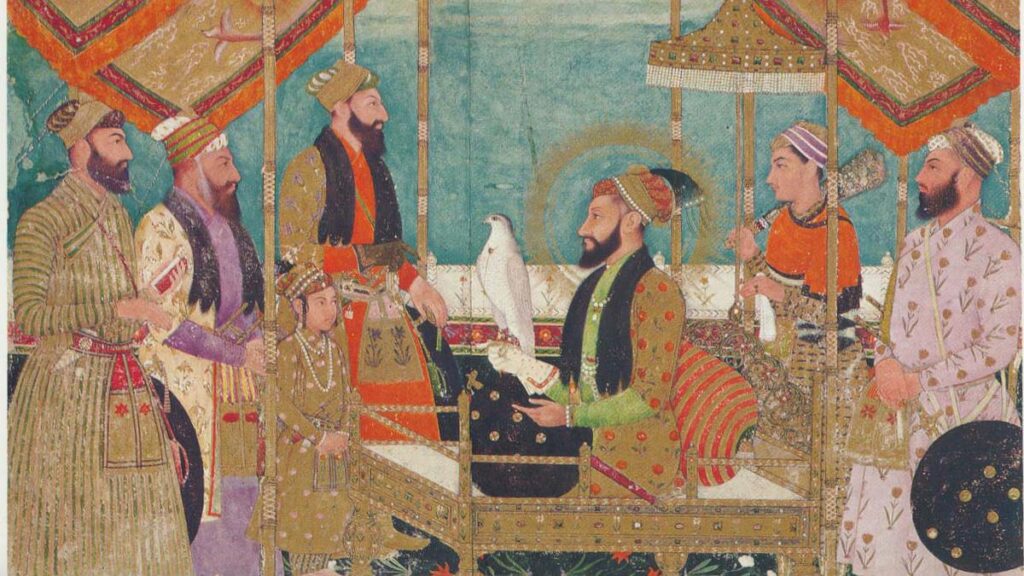

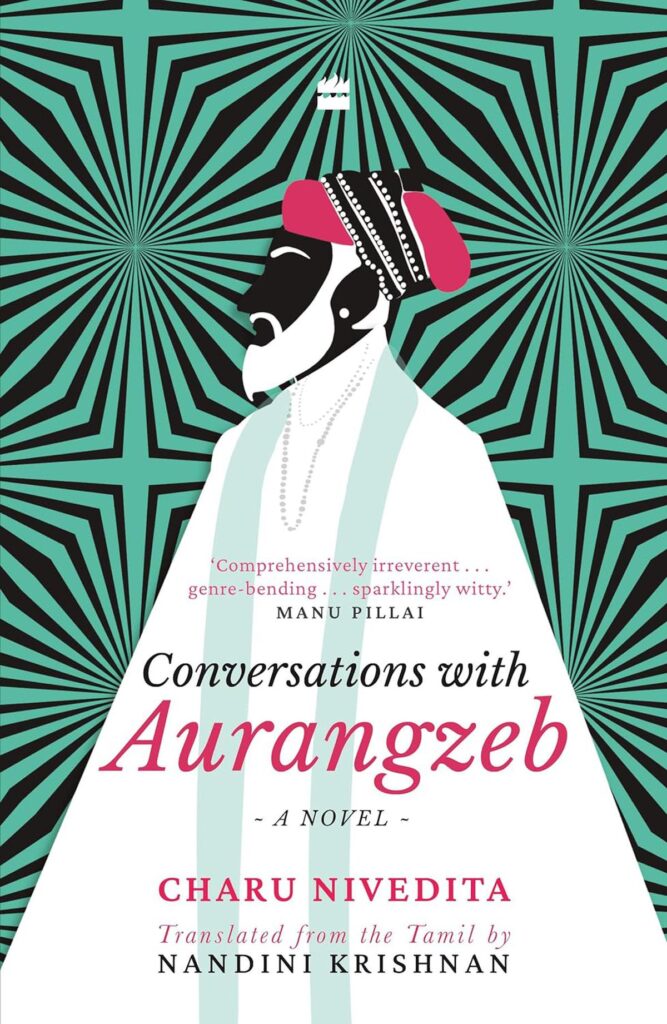

‘Conversations with Aurangzeb’ reimagines the story of the most controversial Mughal emperor

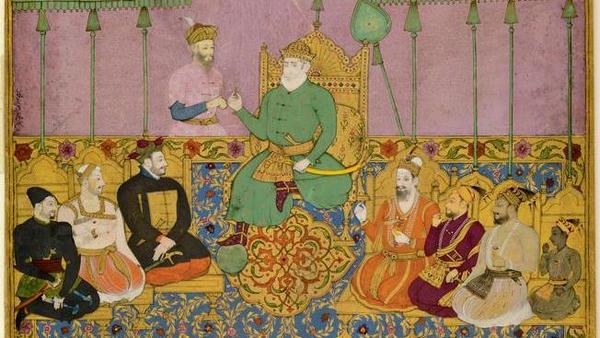

Tamil writer Charu Nivedita’s Conversations with Aurangzeb, translated by Nandini Krishnan,is an unpredictable book. In it, a writer begins a novel with an idea but soon meets the spirit of Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, who decides to seize the opportunity to tell his side of the story. This is an irreverent, indignant Aurangzeb, most unlike the historical character we are familiar with.The writer and Aurangzeb speak of the past and present, of Mughals and Marxism, of satire and Sunny Leone, and a host of other contemporary subjects. Krishnan says the novel is “defiant of all genres”.

discuss the wildly imaginative book, their collaborative process, and the latest translation fad. Edited excerpts:

You’ve given an unpopular historical figure a voice to defend his actions. In a country where satire is often lost on a lot of people, did you ever feel this book was a risky proposition?

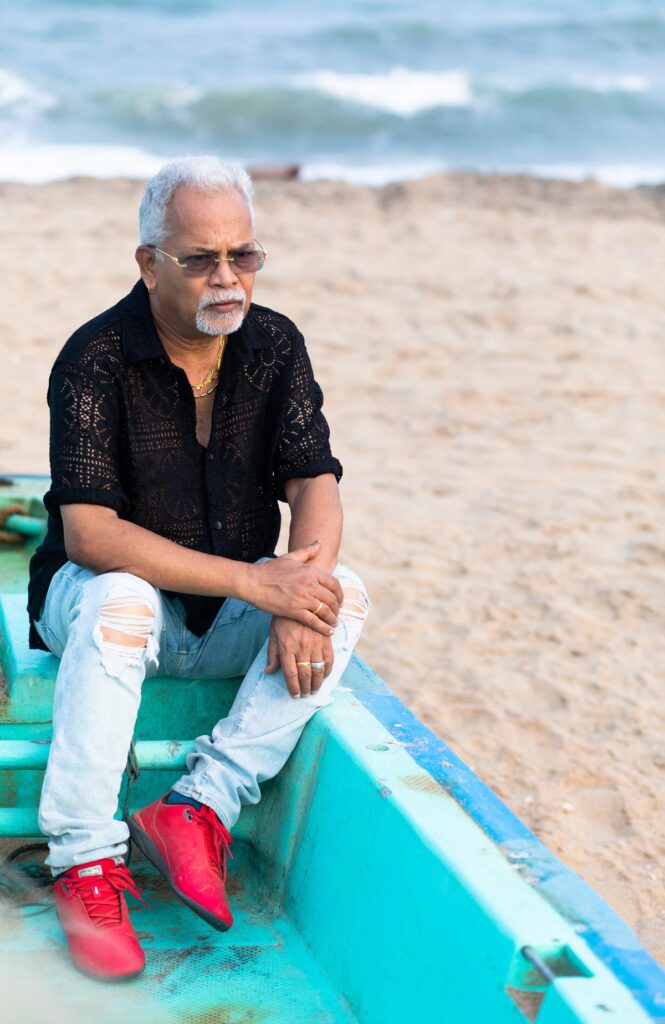

Charu Nivedita: All my writing is risky because I always choose taboo topics. I have always been a misunderstood guy. In a historical perspective, Aurangzeb is also a misunderstood guy. So, I find some similarity between Aurangzeb and myself as a writer.

There are Tamil references throughout the novel. Why and how did you decide to weave these in?

CN: Even though I live in Tamil Nadu, I don’t agree with the culture here. My fellow writers don’t consider me a writer; I always feel like an outsider. Though I write in Tamil, I imagine a European, South American or an Arab readership. I mock the land in which I live. I feel sometimes that I live in a circus when I see the film industry, the paal abhishekam (a ritual of worship with milk)for the cut-outs of actors, or the happenings in the political arena. Self-mocking is important. One who is ready to parody himself or herself can do that with others.

You have said in your translator’s note that some books are untranslatable. Why is that?

NK: I mean there are certain books that are extremely localised. For example, anyone in India who has watched Hindi films would find the line ‘Kitne aadmi the? (How many men were there?)’ funny in any context. But if you’re going to use that line with an American audience or with someone who doesn’t watch Hindi films, it would make no sense at all.

The history of Tamil cinema is as old as modern Tamil writing. There are constant references and cross-references to it in literature. Even in (Nivedita’s) Zero Degree, there is a reference to a scene from the film Chinna Gounder. Unless you get its context, it is not jarring or funny or discomfiting in any way. That’s why I felt Zero Degree was untranslatable.

There is a larger reach now of Tamil books for an English reading audience. What do you think of this translation boom?

NK: Right now, translations are sexy because Geetanjali Shree won the International Booker Prize in 2022. In the 90s, because of Vikram Seth’s enormous advance and later because of Arundhati Roy’s Booker win, Indian writing in English became sexy. This is just a fad. This has also given space to some very subpar translations because everyone is trying to get 20 books translated. We need to maintain the quality of someone like a Charu Nivedita or Ashokamitran or Perumal Murugan or Thamizhachi Thangapandian. Translations do have reach, but does the same quality of work reach an audience? I don’t know.

Also, there is a lot of focus on the writer’s story rather than the story that the writer is telling. And by that, I mean the writer’s gender, caste, their politics, and so on. Unless we go beyond these to the quality of their stories, we are in trouble.

CN: There is a translation boom. But unless there is a miracle, as in the case of Perumal Murugan or Vivek Shanbhag, one is unknown outside their own region. I am unknown outside Tamil Nadu or Kerala. There is no controversy or award because of which people might know me. This is the sad state of affairs.

radhika.s@thehindu.co.in

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Litfest> Interview / by Radhika Santhanam / January 18th, 2024