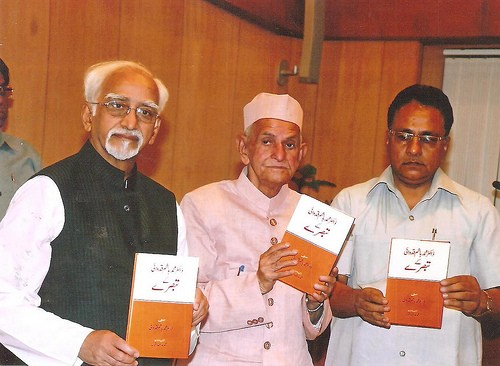

Burahan Ka Tala Village (Barmer District), RAJASTHAN :

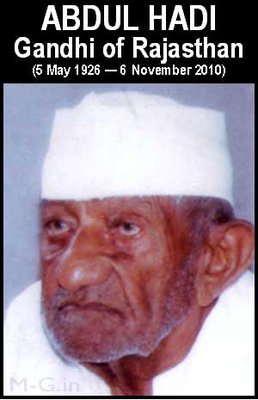

Alhaj Abdul Hadi, a prominent public representative of western Rajasthan passed away in the government hospital, Barmer, on 6 November 2010. He was born on 5 May, 1926.

He led a life full of struggle and was elected an MLA seven times. He belonged to a famous martial race samma (Sindhi) family. His ancestors were religious and learned people. His father Alhaj Mohammed Hasan was a great Moulvi of his time. He was a poet of Sindhi language. He was a scholar of Sindhi, Urdu, Persian and Arabic languages.

Abdul Hadi published his father’s poetry in Sindhi language as ‘Bayaaz-e-kosri’ in 1999. Before partition, Sindh and Rajasthan were very close. Sindh was a prosperous region. Those interested in education would visit Sindh which was a great seat of knowledge in those days. Moulvi Mohammed Hasan Hadi’s father received his education in Sindh. Abdul Hadi respected his father too much and served him well till his end.

Abdul Hadi was a man of letters and had a good knowledge of Sindhi, Hindi, English and Urdu languages. He was fond of Sindhi sufi saint poet Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai and used to study Shah Abdul Latif’s ‘Risala’ regularly along with the recitation of the Holy Qur’an. Abdul Hadi joined politics in his teens for the service of the people. He was a great freedom fighter and active associate and follower of Jai Narayan Vyas who himself was a great freedom fighter and architect of modern Rajasthan. He was the Chief Minister of Rajasthan in the formative years of the state. In those days zamindari system was abolished which made feudals very angry. They used to harass and persecute poor farmers for taxes on land – a system abolished after the freedom of India. Abdul Hadi had been Sarpanch of Burhan-ka-tala tehsil of Chohtan in Barmer in the beginning of the Panchayati Raj. He rose from grass roots to the level of representative of state and further national level.

He was the pradhan of panchayat samiti of Chohtan 1959. He had been the president (Adhyaksh) of Central-Co-operative Bank from 1972 to 1980, i. e. for almost a decade. He had been the District President of Congress (Adhyaksh) twice for the district of Barmer. For 11 years, during 1995-2006 he had been a member of the All India Congress Committee and was a member of the State Congress Committee for many years. He was elected member of the legislative assembly for the first time in 1953 from Sanchore when Chohatan and Sanchore formed one assembly segment. His periods of assembly membership are as follows:

______________________________________

Election year / Constituency

1953 Sanchore, Dist. Jalore & Barmer

1967 Chohatan, District Barmer

1971 Chohatan

1975 Chohatan

1985 Chohatan

1990 Chohatan

1999 up to 2004 Chohatan

__________________

Chart :

Abdul Hadi was a man of character and full of virtues. He was a disciplined politician, selfless, large-hearted, most secular and most obedient servant of the people of border area. He was closely associated with the first generation of Indian political leaders after independence like Nehru, Maulana Azad and Rafi Ahmad Qidwai. He was very close to Indira Gandhi who had great respect for him and had a special liking for Barmer and Jaisalmer and always remembered Abdul Hadi whenever she visited the area. Abdul Hadi had great personal qualities like piety, honesty, hospitality and patience and led a frugal life style. He was very kind to farmers, down trodden and poor people irrespective of caste, creed and religion. He would never surrender before an oppressor.

In 1956, his relative Mohammed Hayat Khan was killed by the notorious dacoit Balwant Singh of village Bakhasar district Barmer. Balwant Singh was an unkind, cruel and ferocious oppressor in the border area of Barmer dist. In those formative years of the Rajasthan state, there was a great menace of dacoits and cattle-lifters. They used to commit robberies and murders and then often absconded to Pakistan.

Abdul Hadi opposed dacoits and led a farmers agitation. Balwant Singh was against Abdul Hadi as he opposed him. Due to Abdul Hadi’s Congress links, Balwant killed his real brother Mohammed Hussain in his village Burhan-ka-tala. He came to kill Abdul Hadi but he was not at his house at the time, so his brother was killed instead. Abdul Hadi fought with legal methods and with the support of the Congress and men like Nathu Ram Mirdha, a kisan leader. Balwant Singh was arrested, tried and jailed. Feudalists and the old system of rulers were finished gradually.

Abdul Hadi was an honest public representative and man of action. In late fifties, there was a dishonest sub-divisional-magistrate posted in Barmer district headquarters. In spite of repeated warnings, he did not improve. He used to take bribes from farmers. Hadi warned him again and again but to no avail. The magistrate used to boast that he was very close to higher ups. Having no other course, Abdul Hadi approached the then Anti Corruption Dy. S. P. Nand Singh Chudawat who was an honest officer. In those days scientific aids of investigation were not of high standards. Dy. S. P. told Hadi that he wanted to see with his own eyes the magistrate accepting bribes. So he changed his dress to look like a farmer of the area. The SDM demanded and received bribe. Caught red-handed, the SDM was promptly arrested for receiving bribe. He was tried and punished by the Supreme Court of India. Abdul Hadi was instrumental in laying this trap.

Abdul Hadi was a real frontier leader not only of minorities but of all western Rajasthan. He was the beacon of Rajasthan from Punjab to Gujarat, i.e. for people living near 1000 kms of international borders Ganganagar, Bikaner, Jaisalmer, Barmer to Jalore, Jodhpur, Sirohi and Pali on the western side of Rajasthan. He was the most trusted sentinel of Indian borders. Abdul Hadi was a man of development. He caused development not only in Barmer district but also in the whole western Rajasthan. He made his efforts for public utility services like roads, water supplies, electricity, hospitals, schools, hostels, community house and other public amenities. For the uplift of society, education is very important. He did all his best efforts to promote education. He helped in the construction of a hostel in Barmer for the students of the area. He emphasized the importance of education. He would say: without education we cannot make any progress in modern world. He used to help poor students financially and morally.

Abdul Hadi lived for the service of people. Whenever there would be some natural disaster, he would extend all his resources for the help of the people. In western Rajasthan, due to erratic and uncertain rains, chronic famines were common. He would always stand up to extend all possible help and would ask the government to start daily wages scheme for the victims. If there were matrimonial disputes or other social issues, he would try to get them solved. If there were agrarian disputes between the farmers, he would always be there to get them solved with the help of the police and revenue officers. If someone was sick, he would be helpful to him by getting him medical and administrative help. He was against use of drugs like opium etc. He also opposed unequal marriages. He was against social evils like “osar mosar” when somebody died. He was against hypocrisy in all forms.

Abdul Hadi was a large-hearted and magnanimous man. He had great rapport with the administration of the district and the state. He was very popular in Congress party circles due to his honesty and candidness. He was clear in his thoughts and would always be helpful for both the administration and public in their hour of need. He would work as a bridge between people and administration. Sonia Gandhi used to call him “Adhyakshji” and would meet him whenever he visited Delhi or she visited western Rajasthan.

While an MLA living in Jaipur’s Vidhaykpuri and MLA quarters, he would help the poor who came from the Barmer district. His house was always occupied by people of his area. He would get up early in the morning and take the needy to the concerned minister and get their problems solved. He was a man of wisdom and action. His approach to ministers and officers was very persuasive and humble. He was loved by the people of his area, his friends, colleagues and administrative officers.

On his death, thousands of people came to pay their last respects to him including all MLAs from Barmer and Jaisalmer districts and western Rajasthan.

A few days before his death, the Chief Minister of Rajasthan Ashok Gehlot came to see him in his village of Burahan-ka-tala. Ashok Gehlot respected him very much. All the administrative officers including the collector were present during his burial in his ancestral graveyard in his native village Burahan-ka-tala.

The author, a retired Inspector General of Police (IGP), had been close to Abdul Hadi since his student days. He had lived with Abdul Hadi in his MLA house for almost three years in the early seventies after completing his education from AMU. He had been his admirer and an ardent follower and was with him on his last day.

source: http://www.milligazette.com / The Milli Gazette / Home> News> National / by The Milli Gazette / March 17th, 2011