KERALA :

The Cheraman Islamic Heritage Museum is now home to the largest digital repository of Islamic history in Kerala.

TNIE speaks to researchers of the team to find out more about the project

Kochi :

About 10 years ago, a clutch of scholars embarked on an ambitious project to unravel the Islamic way of life by documenting and digitising its storied legacy. This work is now complete and available for public viewing at the Islamic Heritage Museum set up on the premises of Cheraman Juma Masjid at Kodungallur.

The project was not confined to unravelling just the centuries-spanning history, but also the lifestyles, literature, cuisine, art and culture. The archive is a treasure trove and contains information on customs, religious rituals, astronomy and navigation, mathematical findings and computation.

To facilitate this, over one lakh documents — texts, sounds, videos and photographs — were analysed by a team spearheaded by the Muziris Heritage Project.

While the data gathered came from all corners of the state, the epicentre was indeed the Kodungallur masjid. Established in 629 CE, it is the earliest mosque in Kerala.

Beyond the colonial lens

Though the contributions of Muslims or Mappila, as they are known in Kerala, are widely recorded, much of it is through a colonial lens. “Of late, historians have been at work to break this norm, shift the practice of tracing history from a land-based approach to encompass our rich maritime heritage. Today, trade documents are also taken into account,” says H M Ilias, an MG University professor and an instrumental member of the team.

As equally important are community lives and the history they tell us, points out P A Muhammad Saeed, another team member. “Documents were collected from families, masjids and madrassas, and private collections of individuals. They provided crucial findings which helped broaden the idea of Islam’s origin in Kerala,” he explains.

The vast collection, which is recorded in four languages — Arabic, Arabi-Malayalam, Malayalam and Persian, also contains the history of migration, the nuances of Sufism and insights into the medical practices of Muslim communities in Kerala.

The origin of Islam

The best place to start tracing the origin of Islam in Kerala was likely within the pages of the first history book in the state — Tuhfat Ul Mujahideen written by Zainuddin Makhdoom II of Ponnani in the 16th century.

“In its two volumes, it talks about the history of Kerala and why Muslims should fight the colonial powers (that it is their religious obligation to do). But beyond this text, we didn’t have much to go by. So during this project, we turned to question that grapples all — the origin of Islam. And Cheraman masjid, the first mosque in India became an intial focus point,” recalls Saeed.

According to the lore associated with the mosque, Cheraman Perumal, a Chera king, on seeing the moon split into two (lunar eclipse), wanted to glean its meaning and possible ramifications. His court and scholars couldn’t offer an answer that convinced him. On learning that there were traders from Arabia in his city, the king summoned them and listened to their ideas.

“Maybe he was found their answers more convincing. For he soon sailed to Mecca to meet the Prophet. That’s what the lore says. What actually transpired could be something different. All kings require a dogma. After the waning of Buddhism, Perumal too was reportedly searching for one. It likely led him to the Arabian shores,” Saeed says.

Perumal converted to Islam on his visit here. But the timeline of this incident remains obscured in history. “For some, it is in the 7th century, and for others, 8th century and 12th century,” says Ilias.

Also, there are two versions to this story, he points out. “One that says Perumal did indeed meet the Prophet. And another one which says otherwise. However, it is said that he died while returning to Kodungallur and was buried at a port in Oman. There are several stories of Perumal entrenched within Omani communities. However, to get epigraphic evidence of this, we need to study archaeological findings there as well,” says Ilias.

According to experts, it is his companions on this journey who, on returning to Kodungallur, propagated the religion in what is today Kerala.

Duffmuttu

Buddhist link

According to Saeed, the Cheraman masjid could also have been a gift to the community’s need for a place of worship. “It very well could have been an abandoned Buddhist temple,” he says, citing the lack of Muslim population around the mosque to back the theory.

Tracing the timeline of Perumal’s travels and the place where he died, he says, the mosque may have come into existence in the 8th century. It underwent major reconstruction after the 15th-century flood that destroyed Muziris port. But confirmations require much more larger research, which includes foreign shores.

However, soon, the project turned big as they began tracing the spread of the religion and the community’s life through centuries. Using lores, folk songs, letters and texts, trade documents and more, they stitched together the larger Islamic history of Kerala.

Rare findings

The digital archive is a repository of rare findings — from the first Quran translated from Arabic to Arabi-Malayalam and the details of Duffmuttu, an art form that some believe to be prevalent even before the time of the Prophet. Originating in Medina, it soon found its way to Malabar and is most prevalent in Kozhikode.

A few medicinal texts — Ashtanga Hridayam (in Arabi-Malayalam) and other ayurvedic texts and documents of Unani are also part of the archive. “Those days, medicinal texts — which included the method of treatment, preparation, precaution and ingredients — were documented in lyrical format,” Ilias says.

The team also found the first travelogue by a Muslim woman. “It was written in the 1920s by a woman who visited Mecca. She talks about her travel and mentions the time both in the Malayalam and Islamic calendars,” Ilias says.

The team included researcher A T Yusuf Ali and the Centre for Development of Imaging Technology, which aided in the digitisation part.

“In earlier times, Kerala was not known for using paper. But those who travelled for trade and Islamic traders who arrived here all carried information on paper. Some of it even resembles thick animal skin. These too are part of the collection,” says Yusuf, who helped collect and digitise the work.

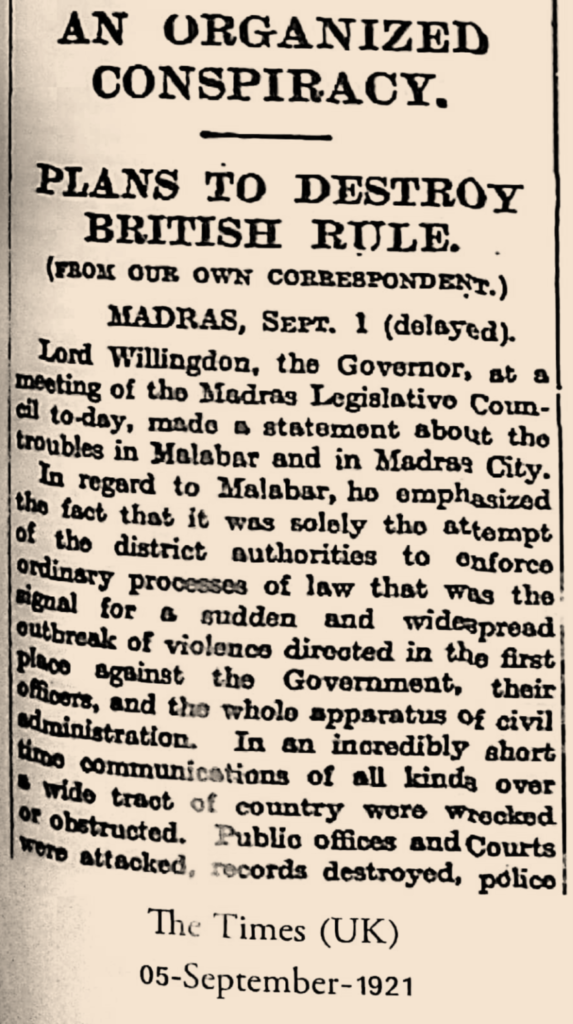

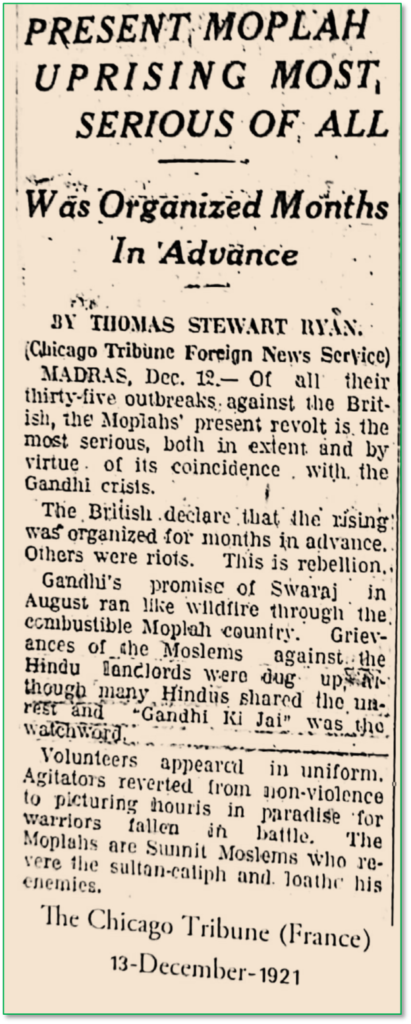

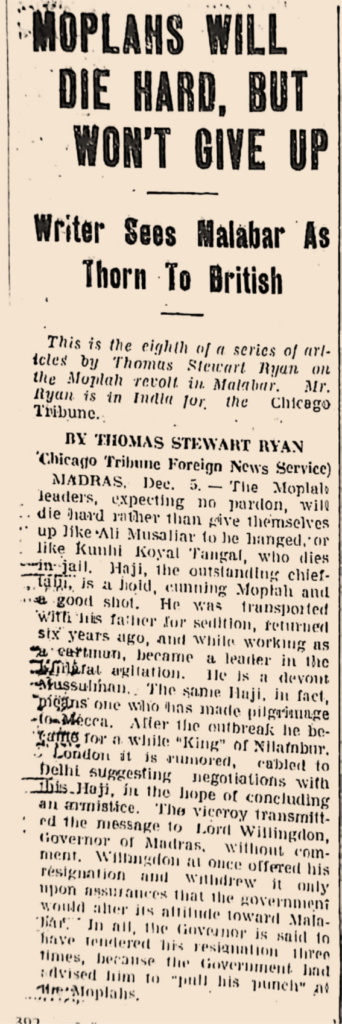

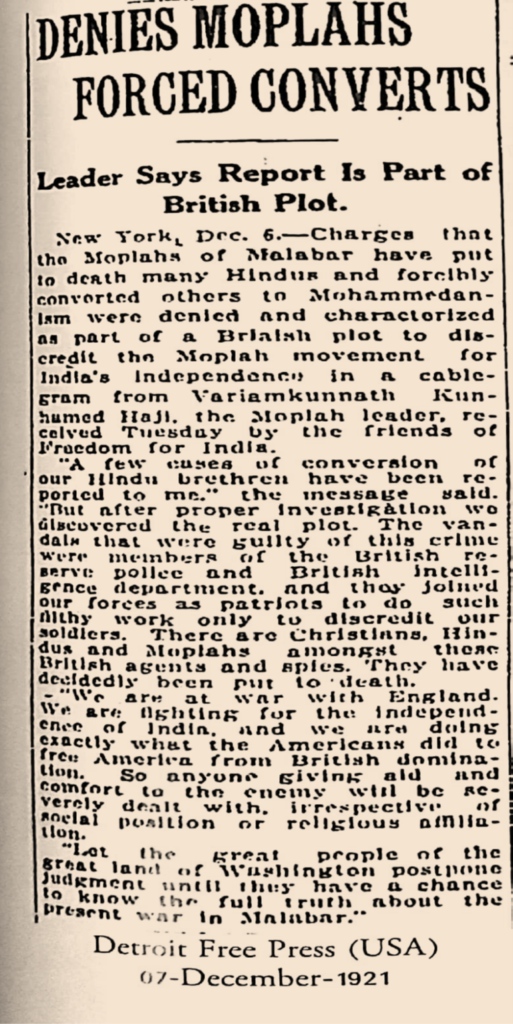

Yusuf, along with the C-Dit team, also spoke to a person who was deported from Malabar to the Andaman Islands. “He was more than 100 years old. Maybe 115. In those days, the British punishment system included deportation to various colonies, including Australia and Southeast Asia,” he says.

Much of the documents were found from Edathola house, Thanoor and Ponanni mosques, houses of Nellikuthu Muhammadali Musaliyar, Abdu Rahiman Musaliyar, Kondotti K T Rahman Thangal and T M Suhara.

The research which started at a narrow point in history has now grown into something big. The Islamic Heritage Museum is one of the largest digital repositories of Islamic way of life in Kerala. “Now, available for researchers and scholars all over the world,” Ilias adds, “it widens the scope of history as we know it.”

Architecture

To study Islamic architecture, the team recorded the history and images of various mosques across Kerala. “There are many mosques which use a mix of Arabic, Persian and Kerala architecture,” informs the team.

source: http://www.newindianexpress.com / The New Indian Express / Home> Kochi / by Krishna PS / July 11th, 2024