Malerkotla, PUNJAB :

In the darkest hour of partition, when the whole of East Punjab was engulfed in a frenzy of communal violence, the town remained calm. And has stayed that way ever since.

Ten years ago, my wife Amarinder and I moved to Bathinda, her home town, to manage a rural school started by her family. For me, a Tamil speaking person originally from Bangalore, it marked a sea change of place and culture. As I gradually acquainted myself with the new rhythms of everyday life in present-day Punjab, I came across sights such as abandoned monuments and ruins battling undergrowth and living Sufi dargahs (shrines) that spoke of the past in an intriguing manner.

It was the shrines that first caught my attention. During my travels in Punjab, I noticed Sufi shrines frequented by people from all communities, the famous Haji Ratan Dargah in Bathinda being one such example. If asked about any dargah dotting the local landscape, people would refer to its past and say that the Muslims who had looked after it originally had all left. In Bathinda itself, of the two schools that were well known before partition – the Khalsa School and Islamia School – the latter no longer exists, for the city has a minuscule Muslim population. In the erstwhile princely state of Kapurthala, the regal Moorish Mosque built in 1930 by Jagatjit Singh for his Muslim subjects – 60 % of the population then – is mostly deserted except for the odd tourist.

The overall demographic of Punjab in the pre- and post-partition period is revealing: Muslims comprise 1.9% of Punjab’s population today in contrast to 51% in undivided Punjab. The Muslim families that one came across in several villages of rural Punjab weren’t usually locals but migrants from Uttar Pradesh or Bihar. My curiosity about Punjabi Muslims remained unabated.

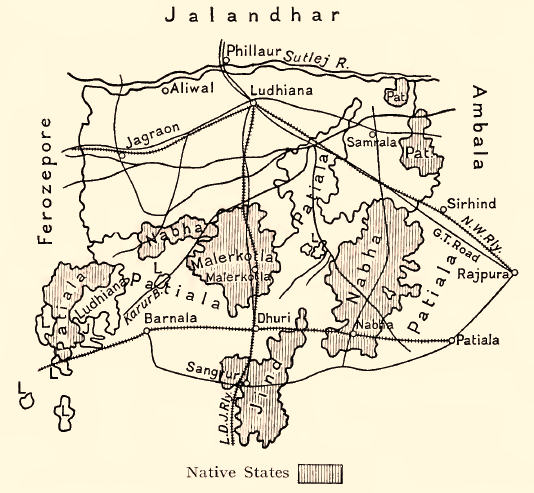

It was during a discussion with my wife’s late grandfather that I first heard the name of Malerkotla – Punjab’s only ‘Muslim pocket’ as he put it, located in Sangrur District. A princely state before Independence, in fact the only Muslim ruled state in erstwhile East Punjab, it was now the sole Muslim majority city in Punjab, he said. And then he told me something that left me stunned: In the darkest hour of partition, when the whole of East Punjab, including the princely states of Nabha, Jind and Patiala, was engulfed in a frenzy of communal violence, Malerkotla remained calm. Not just that, it became a life-saving refuge for Muslims on their way to Pakistan. Anybody I spoke to on this topic echoed the same sentiment.

Around that time I happened to watch Ajay Bhardwaj’s Punjabi documentary, Rabba Hun Ki Kariye (Thus Departed Our Neighbours), based on the memories of the partition generation. In the film, a resident of Malerkotla recounts how Muslims were chased by mobs till the borders of the state and no further, as if something stopped them from crossing the line.

What I gleaned from conversations, articles and scholarly writings was that even after independence, during several critical flash points in the history of the state and the nation, such as during the years of militancy in Punjab or the Ramjanambhoomi movement leading to the Babri Masjid demolition, Malerkotla remained committed to the spirit of communal harmony that has been a defining aspect of its history. An aspect all communities choose to remember as part of their local history, folk memory and heritage.

Not that this place has been in an eternally idyllic state. As scholar Anna Bigelow notes in an illuminating paper, the conditions that provide fodder for social conflict and make communities “riot-prone” in South Asia have existed in Malerkotla as well, be it flash points between religious groups or economic and political rivalries between communities. The difference, she emphasises, lies in the proactive intent of “local authorities and residents to make the unique history of the town a symbolically significant resource for community building and pluralism in the present.”

Living in times of increasing intolerance for the notion of pluralism, this aspect struck me as being of immense importance. Among the myriad strands that make up local histories and folk memory, some are positive and create common ground, while others are contentious. That the communities of a particular place should choose to recognise their shared history of mutual cooperation as their biggest strength and work towards resolving conflicts in the interests of mutual co-existence was incredible.

Unravelling the 500 year old skein of Malerkotla, ruled by nawabs of Afghan Pathan descent, was an instructive exercise. In 1454, the Maler settlement was granted to the Sufi saint Shaikh Sadruddin Sadar-i-Jahan, commonly known as Haider Shaikh, by the Lodis who preceded the Mughals in Delhi. The princely state of Malerkotla (the fortress city) came into being in 1657 when Haider Shaikh’s descendant, Bayzid Khan was given the title of nawab by the Mughals.

Thereafter, the fortunes of the tiny princely state kept see-sawing as it went through a series of alignments and realignments in a time of shifting politics common to the region in the 18th century – local kingdoms fought each other repeatedly in different permutations, sometimes on the say-so of more powerful powers, be it the Mughals, Marathas, invaders such as Ahmad Shah Abdali, or Maharaja Ranjit Singh. With the gradual waning of Mughal power after Aurangzeb, the nawabs sought to assert their independence – in the mid-18th century they supported Ahmad Shah Abdali. During the time of Ranjit Singh (1799 – 1839), they allied with the Sikh kingdoms of Nabha, Jind and Patiala to stay out of his grasp, ultimately accepting British protection in 1809. In January 1872, during the Kuka rebellion by the Namdharis, who were opposed to the British, 69 members of the sect, including some women and children, were strapped to a cannon and blown away on the orders of the British Resident. The nawab of the day was still a minor.

As independence brought British rule to an end and partition became a reality, Malerkotla, the sole Muslim ruled state in erstwhile East Punjab, found itself in a vulnerable position. Yet it survived virtually intact.

The most common explanation given by locals and people across Punjab is the role played by Malerkotla’s celebrated ruler, Nawab Sher Mohammad Khan (1672-1712), during a significant period of Sikh history. It was a time when the increasing following commanded by the Sikh gurus posed a serious challenge to Mughal authority. Although the nawab supported the Mughals in their campaigns against the Sikh gurus, he protested the decision of the Mughal governor to brick alive two sons of Guru Gobind Singh who were captured in Sirhind in 1705. In the nawab’s eyes, it was an un-Islamic act to punish the children when the battle was against their father.

Though this nuanced and principled stand fell on deaf ears, Malerkotla came to command a special place in the hearts of Sikhs. In the popular imagination, Guru Gobind Singh’s blessings ensured that the princely state remained virtually untouched by the communal violence that engulfed the neighbouring Sikh kingdoms. The protective power of saints across denominations, including figures such as Haider Shaikh, is also cited as one of the reasons for its good fortune.

Bigelow adds that the enlightened policies pursued by the Nawabs at critical junctures fostered the spirit of harmony and co-existence in the kingdom. For example, when Bayzid Khan established the foundation of Malerkotla, he summoned a Chishti Sufi saint, Shah Fazl, and a Bairagi Hindu saint, Baba Atma Ram, to bless the site, thereby declaring his faith in pluralism.

The princely state is a thing of the past, but Malerkotla continues to be in a league of its own even in democratic India (at the time of independence, it had a population of 85,000 in an area of 432 sq km). The fact that it has survived in its present demographic form is an indicator that the spirit of co-existence is still alive: as per the 2011 Census, Muslims, a minority in India and a tiny minority in Punjab, comprise 68% of the city’s population of 1.35 lakh; Hindus, the majority community across India, are placed at 20%, while Sikhs, who comprise the majority in Punjab, are only 10%. The current MLA, Farzana Alam (Akali Dal), has the distinction of being Punjab’s first non-Punjabi state legislator (she is originally from Uttar Pradesh).

Punjab has witnessed communal conflicts between Hindus and Muslims, and Sikhs and Muslims as well as between Hindus and Sikhs in more recent times during the days of militancy. Malerkotla has not been entirely free of flash points arising out of these developments.What sets it apart is that the focus of local authorities and community leaders at all times has been not only to defuse the situation but to approach it in a way as to foster greater solidarity, in keeping with its heritage.

Over a period of time, integrative practices like communal celebration of festivals, visits to each other’s sacred sites and mixed residential localities and joint businesses have helped immensely. Heritage organisations too have done their best to keep alive the memory of the city’s plural traditions. Bigelow cites two examples to illustrate how incidents threatening to upset the peace have been contained: In the aftermath of the Babri Masjid demolition in 1992, some Muslim youths vandalised a Hindu temple and Jain Sabha hall. Local Muslim leaders promptly checked them; some Muslims came forward to pay for the damage, while the Muslim MLA ensured that funds from the state were used for the complete restoration of the damaged buildings. The local Hindus too opted to work with local peace committees. The final message that was sent out was that there was no place for such acts in Malerkotla.

In the other incident, the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas by the Taliban in 2000 led to several anti-Muslim actions – in one place the Quran was burnt, at another place pig meat was hurled into a mosque. To protest the Bamiyan Buddhas’ destruction and the local acts against Muslims, the Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs went on a general strike for a day. Says Bigelow, a potentially divisive issue was “transformed into an act of symbolic solidarity against a variety of injustices.”

In the ultimate analysis much of the credit goes to the general population which has proved to be far wiser than it is sometimes perceived to be. The lived reality of Punjab’s sole Muslim-majority city, echoing aspects of a Punjabiyat that once exemplified the region, is a pointer to the fact that pluralism is the strongest weave for a democracy like India, and the strongest antidote to the intolerance of majoritarianism.

Karthik Venkatesh runs a rural school in Bathinda, Punjab

source: http://www.thewire.in / The Wire / Home> Culture / by Karthik Venkatesh / January 16th, 2016