Kilakarai (Ramanathapuram District) , TAMIL NADU :

Legends abound in Tamil folklore about the ‘merchant prince’ Shaikh Abdul Qadir, popularly known as Seethakathi. He was one of the earliest regional traders to do business with the Dutch and the British in the 17th Century. A generous patron of the arts, he supported poets Umaru Pulavar, Padikasu Thambiran, Kandasamy Pulavar, and others.

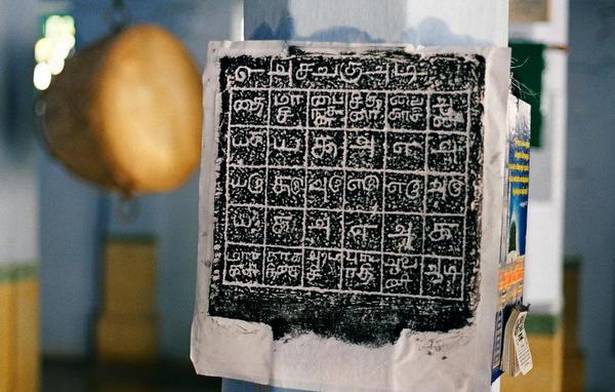

Cultural confluence: The prayer hall of the Grand Jumma Masjid, which is central to the landscape of Kilakarai. It was built in the 17th Century in the Dravidian style of architecture. | Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

In Tamil, Seethakathi is a byword for philanthropy. The adage ‘Seththum kodai kodutthan Seethakathi’ (Even in death, Seethakathi donated generously) is often used to refer to a person’s exemplary munificence. But who was Seethakathi, or rather, Shaikh Abdul Qadir, who also sported the title, Vijaya Raghunatha Periyathambi Marakkayar, endowed by Kilavan Sethupathi?

Legends abound in Tamil folkloric narratives about this ‘merchant prince’ of the coastal town of Kilakarai, in the present day Ramanathapuram district, whose name is variously spelled as ‘Seydakadi’ or ‘Sidakkali’. Actual evidence of his enterprise and influence, however, has survived only in a handful of records and inscriptions of the late 17th Century.

In memoriam

Kilakarai continues to commemorate its famous son. The main thoroughfare here is called ‘Vallal Seethakathi Salai’, and a grand memorial arch in his name on the outskirts welcomes visitors. An annual ‘Seethakathi Vizha’ is organised with panegyric poems and speeches in his honour.

Central to Kilakarai’s landscape, though, is the Grand Jumma Masjid, built in the Dravidian style of architecture, where Seethakathi is interred.

The mosque, said to have been commissioned by Seethakathi or built during his lifetime in the 17th Century over two decades, also houses the graves of his elder brother ‘Pattathu Maraikkar’ Mohamed Abdul Qadir, and the domed mausoleum of the saint-scholar Shaikh Sadaqatullah (known locally as Sadaqatullah Appa), to whom Seethakathi was close, both as disciple and friend. Seethakathi also commissioned the grave of his younger brother Sheikh Ibrahim Marakkayar in Vethalai.

“This mosque has 110 pillars made with stone quarried from the seashore in Valinokkam village. Its style is typical of southern Indian buildings of its time, and is of great interest to researchers because of its unique structure. All the pillars are embellished with floral patterns, and some of them are naturally embedded with seashells,” A.M.M. Kader Bux Hussain Siddiqi Makhdoomi, the town Qazi and ‘Mutawalli’ (administrator) of the Grand Jumma Mosque, told The Hindu.

Blending with locals

According to research by S.M. Hussain Nainar (1899-1963), who was a professor of Arabic, Urdu and Persian at the University of Madras and Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati, Arabs and Persians had been trading with the Indian peninsula even before the advent of Islam. Over time, the Arab traders settled along the coast of southern India, and with the coming of Islam, became assimilated with the local population. Most Tamil-speaking Muslims in these regions have Arab ancestry.

Islam’s influence in the Deccan has been noted from the end of the 13th Century, but it peaked only after the mid-17th Century, in the reign of Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb (1658-1707).

Born to Malla Sahib Periya Thambi Marakkayar and Syed Ahmed Nachiyar, as the second of three sons, Seethakathi hailed from Selvarkulam. The Marakkayars (an abbreviated form of Marakala Rayar) were one of the five early Tamil Muslim communities (the others being Sonakar, Labbai, Turki and Rowther) mentioned in historical texts.

The Marakkayar community was known for its maritime trade, and Seethakathi made his fortune in dealing with pepper, rice, pearls and handloom textiles, among other commodities.

Seethakathi was a close friend of Vijaya Raghunatha Thevar, or Kilavan Sethupathi, a loyal vassal of Chokkanatha Nayak, who helped Thirumalai Nayak in his war against the Mysore army.

Sethupathi cut off ties with Madurai in 1792 and built the Ramalinga Vilasam palace to fortify his position in the region. The palace, set in the middle of a moated campus, has a stone tablet that bears Seethakathi’s name.

The title, ‘Vijaya Raghunatha Periya Thambi’, denoted the affection and trust that Seethakathi enjoyed of his royal friend.

Mughal ‘khalifa’ in Bengal

It is also said Shaikh Sadaqatullah’s mention of Seethakathi’s generosity and character to Emperor Aurangzeb resulted in the ‘merchant prince’ being sent to Bengal as the Mughal ‘khalifa’ (regent). However, Seethakathi decided to resign after a while, as the new environment did not suit him.

Seethakathi’s acumen helped him become one of the earliest regional traders to do business with the Dutch and the British in the 17th Century. He is known to have maintained ventures from the Coromandel Coast to Sri Lanka (Ceylon). The British made contact with Seethakathi in the mid-17th Century.

Nainar’s 1953 book Seethakathi Vallal refers to the correspondence, in 1686-1690, between Seethakathi and the British East India Company’s agents William Gyfford and Elihu Yale negotiating trade in pepper and rice. The Dutch, too, interacted with Seethakathi, first as business rivals, and then as collaborators.

Patron of arts

Seethakathi was a generous patron of the arts, with poets like Umaru Pulavar, Padikasu Thambiran and Kandasamy Pulavar among the many supported by him.

Umaru Pulavar wrote the Seera Puranam, a 5,000-stanza verse biography of Prophet Muhammad in Tamil. Nainar’s book also contains two extant literary works about him: Seethakathi Nondi Nadagam (a Tamil mono-drama) and Thirumana Vaazhthu (felicitation written for Seethakathi’s wedding).

“Over time, many myths have become attached to Seethakathi. As archival documents show, he was a successful businessman and ‘rental farmer’ for the powers of the day. More systematic research of old records would help to highlight the role of Tamil Muslims like Seethakathi in Indian history,” said J. Raja Mohamed, historian and former curator of Pudukottai Government Museum.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> News> India> Tamil Nadu> In Focus / by Nahla Nainar / October 27th, 2023