The master’s style became so well established that it has come to stay.

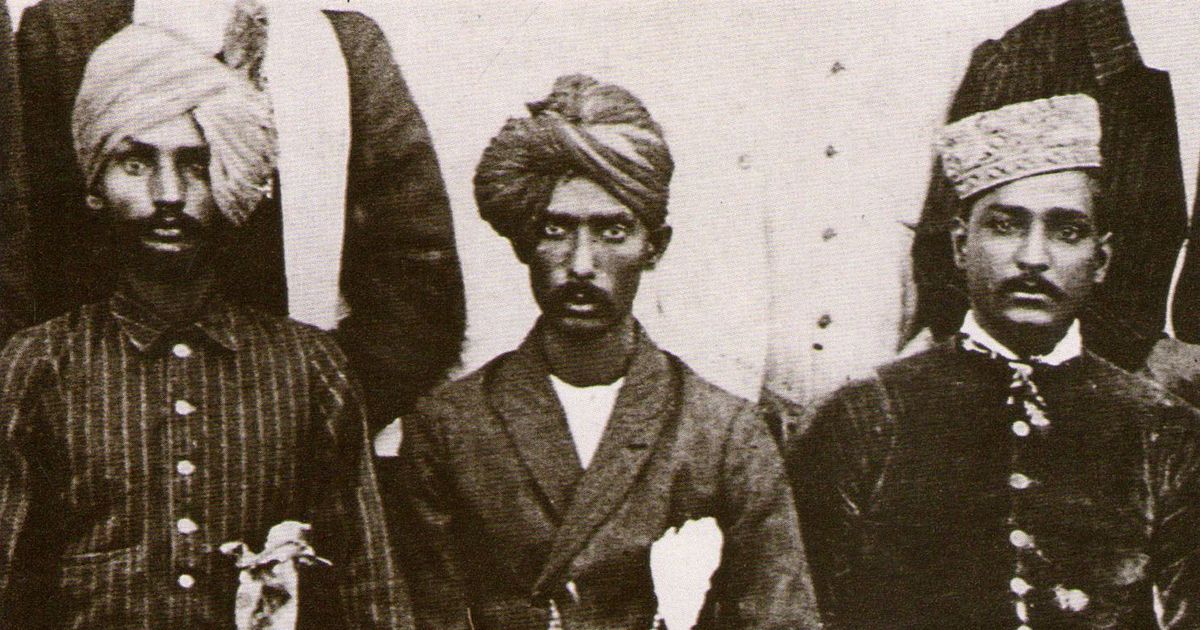

Abdul Karim Khan was born on November 11, 1872, at Kirana, a village near Panipat. His father, Kale Khan, was also a musician and Abdul Karim and his two other brothers, Abdul-Majid and Abdulhug, imbibed their earliest lessons in music from him. It is said that Abdul Karim and one of his brothers left Kirana when they were still in their teens and came to Baroda where Abdul Karim soon earned a name for himself as a young poet and talented musician.

He then left Baroda and travelled to Poona and Bombay. He imparted his knowledge of music to a few earnest students and soon established himself as an outstanding musician of the Kirana gharana. He finally left Bombay and settled in Miraj, which was then a princely state. Among the well-known musicians of his time, he was the first who studied the complex problems of shruti. He was the principal and perhaps the only demonstrator of the shruti scale of the chromatic scale of Hindustani music. He demonstrated that the subdivision of the seven notes of the usual gamut into 22 parts was a fact to be reckoned with and not just a fantasy in the minds of ancient musicologists.

Abdul Karim was a man of simple and frugal habits, non-ostentatious and kindhearted. He did not bully or ill-treat his pupils and those who lived with him enjoyed parental care and attention. At Miraj, he developed an interest in the tanpura and brought his own musical knowledge to bear in the construction. He was on his way to Pondicherry when he experienced a severe pain in the chest at Chingalpeth. On October 27, 1937, he died peacefully on the platform at Singapuram Koilam, reciting Kalma in the raga Darbari.

We find it a little difficult to understand how it is that geophysical regionalism has become synonymous with the history of gharanas rather than the names of those maestros who have devoted their lives propagating and teaching the mode of music perfected by them in their own way and after their own heart. Is it the typical oriental philosophy of the impermanence of man that is responsible for the transference of credit and merit from man to place?

Geography of music

Tansen’s disciples made his music the music of the Gwalior gharana; Alladiya Khan’s complex music came to be linked with Jaipur or Atrauli; Fayyaz Khan and Vilayat Khan belonged to the Agra gharana; Bade Ghulam Ali was associated with the Patiala gharana; and Abdul Karim’s cultivated pattern of music came to be known as the Kirana gharana. Our inquiry into this aspect may not lead us on to any definite results. But it is important to explore how a gharana is born.

Let us consider the Kirana gharana and its distinguishing points. First, not much is known about Abdul Karim’s teacher, his father, Kale Khan. Abdul Wahid Khan, another exponent of the Kirana gharana, learnt his music from his father Hyder Khan. Not much is known about him either. Bande Ali Khan, the been maestro, is said to have belonged to this gharana and except for his celestial music and the romance which culminated in his marriage to his disciple, Chunna, there are few mentions of the Kirana gayaki. Most accounts of musicians, both living and dead, are anecdotal. They do not give us even a glimmer of the manner in which these great masters imbibed their music, the methods, the routine they followed and the influences which worked on them. It is not possible to convey accurately the idea of a gharana through words because our musical aesthetic or critical vocabulary have yet to arrive at a stage of absolute precision. It is still in a state of evolution. A listener feels the stamp of a gharana and there it rests; the musician, guided by his fancy and immersed in his own interpretation, has already left familiar ground and is in his own world where the gharana is as far removed from him as an airman from terra firma.

A common observation about the Kirana school is that the musician develops his song or cheeja merely on the strength of the alapi or elongated notes, so dovetailed that in his exposition of the melody, his only aim is to fix and cajole or caress a note, the only limitation being that of tala (the time measure), which beckons him to the point of return. The sweetness of melody is primarily due to the tonal quality, which imbibes a gradual, subtle use of semi-tones in the main note, whose placement in the scheme of the melodic weave is the main objective. For him the cheeja are only a help in articulation.

The Kirana musician seems to have all the time in the world once he has started and closed his eyes to mundane things like the audience. He weaves his net of alapi around a note and ascends the melodic structure as delicately as a gossamer spread over a leaf. He is in love with his swara he has captured that very moment. He plays with it, is engrossed in its nodal and sub-nodal musicality. This has provoked derisive and wholly unjustified remarks from listeners. They say if one Kirana gharana musician takes half an hour to reach gandhar, another musician of the same gharana will take one hour to do so.

The form matters

Some musicologists are of the opinion that this gayaki lacks form. The existence of so many gharanas is proof that what is termed form is an elastic, accommodative arrangement and not a principle of scientific rigidity. In our music, the artiste sets out and sings a cheeja perhaps once; he enunciates it properly and then begins to establish the melody in a multi-pronged manner. The chosen melody is set to a particular tala, and his beginning in slow tempo necessitates a slow and leisurely progress. Each school of music has decided over a long period of deliberation and practice its own mode of such measured progress. If we compare two music lovers’ assessments of a gharana, both of them may agree on the overall effect of the music but often disagree on individual movements or methods of elaboration. In our music there is really nothing inherent which dictates to us that only one arrangement is possible. Witness, for example, the different ways of enunciating the world kaku in Sanskrit musical treatises. Witness, also, the musician’s improvisations in changing the stress for the sama. One can pile up a whole list of such individual gimmicks employed by a musician.

In our music, the basic material is the melody or abstract series of sounds related in an artificial manner. These sounds are subject to some arrangements: for example, five-note ragas, six-note ragas and so on. It is easy to understand that once this arrangement is stretched over a composition, that is, on the musical theme, the musician is permitted a great amount of freedom in his handling of it. When we think of form in our music, we have to think of the sound content and not of a rigid structure superimposed on a cheeja and its movement. Hindustani music, is not written and, therefore, the duration of a performance differs from musician to musician. If a musician compresses all his art in a short period of time and another stretches his recital over a longer span, we do not consider it amiss. The total impression is what we finally have in mind.

When a Kirana musician creates an agreeable atmosphere of a melody by a succession of notes woven carefully and gradually, and when he expounds the cheeja with finesse and keeps you rooted to your seat, you cannot merely dismiss his art, and his effort as charming yet formless. We will have to grant then that the Kirana musician has evolved his own form and this is no mean achievement.

Focus on swara

A distinctive feature of this school of music can be briefly summarised thus: a Kirana musician places greater stress on the presentation of melody by employing alap or lengthened flights of swara continuation, running through the full time-measure. He does not play within the inherent rhythm or laya in the manner of a musician of the Agra gharana. In fact, his obsession with the swara overshadows every other facet of the presentation of music. He does not unfold the melody through playful hide-and-seek either with the time-measure or with intricate and complex variations of the rhythmic pace. His main concentration is on the note or swara, and with this as his base, he creates an atmosphere of deep reverence. A listener who concentrates on the performance notices that the Kirana musician does not deal with scattered or separate musical ideas, individual movements within the time-circle but builds up his melody, note by note, like a weaver.

Another distinctive feature of the Kirana musician is his voice culture. His gestures seem to indicate that he is really at great pains to produce a sound, and that he has some difficulty in sustaining it; but actually the artiste is not greatly constricted in his articulation. The Kirana musician’s sense of control of the subtle inflexions in voice production is remarkable and he has had to strive hard to attain it. He seeks to achieve the desired tunefulness. But his mannerisms appear somewhat odd; even so, they are natural to him. In his taans, there is more facial or jaw-bone control. The Kirana musician elaborates the sargam or notation of phrases deftly and in an ingratiating manner. In fact, this has become one of the notable and accepted ingredients of this gharana. His vocal line has a wide range – wider than that of most of the musicians of other schools of music.

One significant aspect of the Kirana musician is his presentation of the thumri in his own cultivated way. The Kirana musician’s voice culture is suited to singing the thumri because there is equal stress on both the composition and its meaningful presentation. The Kirana musician’s delineation of a thumri is again swara-dominated and tends towards a khayal pattern.

A genius arrives

Abdul Karim evolved and perfected the style entirely on the basis of his own genius. There is a gramophone disc of Abdul Karim, rare, yet still available in the possession of connoisseurs. It reveals an entirely different kind of musician. One can hardly place the musician as Abdul Karim even after ten guesses.

It is clear that Abdul Karim pondered over the problems of musical expression. He was gifted with a sweet and extremely pliant voice, which he cultivated in his own rigorous manner and it is on record that he enjoined his disciples to conform to the voice culture he taught them and to perfect it through persistent practice. Abdul Karim could reproduce all the 22 shrutis of our chromatic scale. Apparently, what we call form came to the musicians through the dhrupad style which was rigid in its structural presentation. Our musical progress, however, is traceable to rebels who boldly deviated from the uncompromising elements in the attitude of the dhrupadiyas. Abdul Karim ought to be applauded for the leadership he took in this battle.

Abdul Karim’s style is now so well established that it has come to stay. He who creates, lives. He has established his own norms, his own code of conduct. He lived at a time when great, very great and even outstanding musicians lived and performed in their own ways. If he rejected some of the ideas of other music styles, he must be applauded rather than accused of departing from them. New and upcoming musicians (like Kumar Gandharva or Vasantrao Deshpande) have also boldly created, established and consolidated their own styles and our music is the richer for their contributions.

Abdul Karim’s performances delighted his listeners. In addition to khayalgayaki, he raised thumri presentation to a new and beautiful state. During his performances, the listener experienced a mental repose. He sang khayal, thumris, Marathi stage songs, Marathi pads. He was not a purist or a dogmatic upholder of a particular tradition. He remained in his own sound of swara-dominated trance the whole day, and those who were close to him say he would pick up a tanpura and tune it to the basic note of a tanpura tuned the previous day, without striking the note of the harmonium for support. This meant that he was in constant harmony with that note both during his sleep and during his waking moments.

This article first appeared in ON Stage, the official monthly magazine of the National Centre for the Performing Arts, Mumbai.

We welcome your comments at letters@scroll.in.

source: http://www.scroll.in / Scroll.in / Home> Magazine> Music / by K D Dixit / October 22nd, 2017