Jallianwala Bagh, (Amritsar), PUNJAB:

In popular memory, historical narratives are more often than not laced with silence, neglect, nostalgia and heroism thus blurring the line between history and fiction. Public memory tends to remember the selective events according to ideological or political conveniences while the whole narrative in its context is often forgotten.

The Jallianwala Bagh Massacre is one such event which stands out in public memory as a solitary incident. Popular imagination puts the killing of hundreds of Indians on 13th April, 1919 at Amritsar as an event completely disassociated from time and space. It is needed that the massacre should be read in context with the time and space.

Why did the people gather at Jallianwala Bagh?

Indian leadership in general supported the war efforts of the British during the World War – I (WWI) on a promise that the country would be granted self rule or some kind of political autonomy after the war would be over. The British, after the war, backtracked on the promise. Rather to check the nationalist voices brought a Rowlett Act in force which enabled police to imprison Indians without evidence. Several Indian Muslims were aggrieved at the humiliation of Turkey and the British believed that it was their only challenge. With the Rowlett Act at their disposal these Pro-Khilafat voices could be easily suppressed. They did not foresee the possibility of Hindus joining hands with the Muslims, and vice versa and pose a problem for their colonial rule.

On 18th March, 1919, the Rowlett Act was passed. Mahatma Gandhi along with other nationalist leaders termed it a Black Act and called for a protest movement against the same. The day chosen for protests and strikes was the 30th March that was later changed to 6th April. In Delhi a protest was held on 30th, because of lack of communication, and the police did not hesitate from firing upon the unarmed people. More than 50 protestors were killed in Delhi. The British had cleared their intention of using violence against the non-violent protesters.

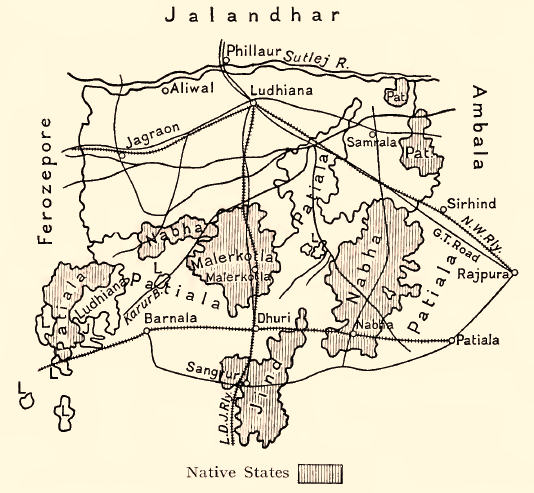

On 6th April protests and strikes were held across the country, yet Punjab displayed an exemplary zeal of nationalism. What disturbed the British most was the fact that orthodox Hindus of Arya Samaj and orthodox Muslims of different Wahabi and pan-Islamist organizations joined hands against the British. The most popular leaders of Punjab at the time – Dr. Saifuddin Kitchlew and Dr. Satyapal, were prohibited from making public statements but still unity could not be broken. At different places people were fired upon but the nationalist sentiments could not be killed.

On April 9, Muslims came out to celebrate Ram Navami across Punjab. This was becoming too much for the British. In Amritsar Saifuddin and Satyapal oversaw a grand Ram Navami procession where Muslims were as zealous as Hindus were. It led the British to arrest the two leaders and sent them to an unknown location. The people gathered at the Deputy Commissioner’s office to register their protest and they were fired upon. Many were killed. The fear of a Hindu-Muslim unity was so frightening for the British that even after Jallianwala Massacre they arrested and killed Muslims for participating in Ram Navami celebrations.

Ghulam Jilani, who was an Imam of a mosque, was arrested on 16th April with Khair Din for leading the Ram Navmi processions. Police tortured them in the most horrific and inhuman fashion by inserting sticks up in their anus until their excreta and urine would not come out. Khair Din died of the torture while Jilani survived to narrate the ordeal. More than a hundred Muslims were tortured in this manner to celebrate Ram Navmi.

On the other hand in Lahore, on receiving this news, in an unprecedented manner more than 25,000 Hindus and Muslims gathered in Badshahi Mosque and Hindu leaders, like Rambhaj Datta, addressed the people from the pulpit of the mosque. In Lahore, not only the British used bullets but also brought their loyalists into the picture.

A few sold out Indians like the leaders of Muslims League issued statements that allowing Hindus into the mosque and addressing from pulpit amounted to the sacrilege. Still, most of the Muslims in Punjab were supporting the war cry of the protestors: Hindu-Musalman ki Jai (Victory to Hindu-Muslims).

It was noted in a government report tabled at the British Parliament, “It (Hindu-Muslim) union had only one purpose, a combined attack on the government.”

Meanwhile, on 13 April, the Baisakhi Day, a meeting was scheduled at Jallianwala Bagh, near Golden Temple, to protest the arrests of Saifuddin and Satyapal. Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs gathered at the Bagh. Colonel Dyer with his troops entered the place and fired upon the unarmed protesters. A gory story of blood, death and massacre happened that each and every Indian knows by heart. Hundreds of Indians died. The tale of this massacre became folklore and inspired generations of revolutionary Indians like Bhagat Singh, Ram Mohammad Singh Azad and others. But, what we miss out is that the British did not stop at this. Punjab remained a laboratory of British atrocities.

The next day, April 14, people in Gujranwala woke up to find a beheaded calf at a public place. It did not take a rocket science to decipher a sinister plot to cause enmity between Hindus and Muslims. People gathered and protested such malicious attempts of the government to disturb the peace. Frustrated at their failed attempt and seeing that the unity has strengthened even further, army airplanes were called in to bomb the city. Yes, you are reading it correctly.

Within two decades of the invention of aero planes and less than a decade of its first military use in WWI when the technology was novel even for armies the British used it upon the innocent civilians of Punjab. A fleet of three planes dropped bombs and fired machine guns on the city and adjacent rural areas. Bombs were dropped at schools, hostels, mosques, marriage ceremonies etc. The government report specifically mentioned that the district is dangerous because followers of Arya Samaj and orthodox Muslim Wahabis like Fazal Ilahi and Zafar Ali Khan had joined hands. An armoured train with machine guns mounted in it was also used to kill along the railway tracks in Gujranwala.

The tales of torture, suppression and killings was repeated allover Punjab. While Jallianwala Bagh rightly gets its mention in our books and survived the public memory the causes behind it and a long trail of violence proceeding and succeeding the event have been forgotten. The very fact that the British used their worst form of violence to counter Hindu-Muslim unity itself speaks about the power of this unity. We need to remember the cause for which our forefathers and foremothers had laid down their lives.

(Saquib Salim is a historian-writer)

source: http://www.awazthevoice.in / Awaz, The Voice / Home> Story / by Saquib Salim / 2021