BRITISH INDIA :

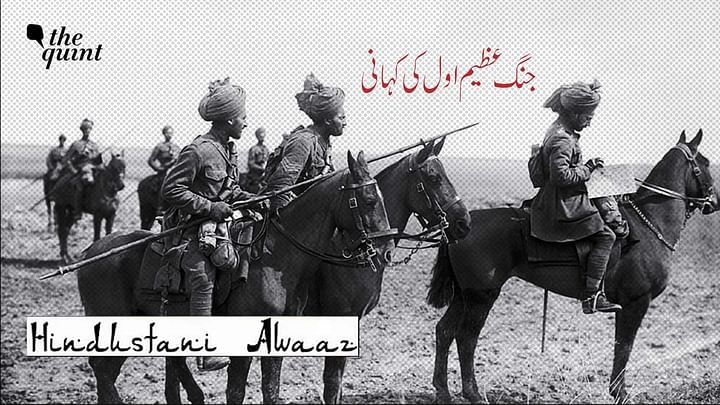

The four years of the World War 1 saw the service of 1.3 million Indians, of whom 74,000 never made it back home.

The First World War , or the Great War as it is also called, raged across Europe and several war arenas scattered across the world from 28 July 1914 to 11 November 1918. These four years saw the service of 1.3 million Indians, of whom 74,000 never made it back home. For their families, the war was something they couldn’t quite understand.

Given the large-scale Indian involvement in a war that the majority of Indians could not fully comprehend, we shall once again look into the mirror of Urud to see how the poet viewed the momentous years of the Jang-e Azeem as the Great War came to be called in Urdu.

Several poets, lost in the veils of time and virtually unknown today, made interventions as did the more famous ones who continue to be well known though possibly not in the context of what they had to say about World War I.

Urdu’s Rendition of the Greatest Human Tragedy

Presented below is a sampling of the socially-conscious, politically-aware message of the poets of the times. Not all of these poets are well-known today nor is their poetry of a high caliber yet fragments of their work have been included here simply to illustrate how the poet had his finger to the pulse of his age and circumstance.

Let us begin with Sibli Nomani and his wryly mocking Jang-e Europe aur Hindustani that deserves to be quoted in full:

Ek German ne mujh se kaha az rah-e ghuroor

‘Asaan nahi hai fatah to dushwar bhi nahin

Bartania ki fauj hai dus lakh se bhi kum

Aur iss pe lutf yeh hai ke tayyar bhi nahin

Baquii raha France to woh rind-e lam yazal

Aain shanaas-e shewa-e paikaar bhi nahin’

Maine kaha ghalat hai tera dawa-e ghuroor

Diwana to nahi hai tu hoshiyar bhi nahin

Hum log ahl-e Hind hain German se dus guneh

Tujhko tameez-e andak-o bisiar bhi nahin

Sunta raha woh ghaur se mera kalaam aur

Phir woh kaha jo laiq-e izhaar bhi nahin

‘Iss saadgi pe kaun na mar jaaye ai Khuda

Larhte hain aur haath mein talwar bhi nahin!’

(Consumed with pride, a German said to me:

‘Victory is not easy but it isn’t impossible either

The army of Britannia is less than ten lakh

And not even prepared on top of that

As for France, they are a bunch of drunks

And not even familiar with the art of warfare’

I said your arrogant claim is all wrong

If not mad you are certainly not wise

We the people of Hind are ten times the Germans

Cleary you cannot tell big from small

He listened carefully to what I had to say

Then he said something that can’t can’t be described

‘By God, anyone will lay down their life for such simplicity

You are willing to fight but without even a sword in your hand!’)

That the Urdu poet was not content with mere high-flying rhetoric and was rooted in and aware of immediate contemporary realities, becomes evident when Brij Narain Chakbast declares in his Watan ka Raag (‘The Song of the Homeland’):

Zamin Hind ki rutba mein arsh-e-aala hai

Yeh Home Rule ki ummid ka ujala hai

Mrs Besant ne is aarzu ko paala hai

Faqir qaum ke hain aur ye raag maala hai

Talab fuzool hai kante ki phool ke badle

Na lein bahisht bhi hum Home Rule ke badle

(The land of Hind is higher in rank than the highest skies

All because of the light of hope brought forth by Home Rule

This hope has been nurtured by Mrs Besant

I am a mendicant of this land and this is my song

It’s futile to wish for the thorn instead of the flower

We shall not accept even paradise instead of Home Rule)

Poems Charged With the Spirit of Revolution

Similarly, Hasrat Mohani, in a poem called Montagu Reforms, is scathing about the so-called reforms that were given as SOPs to gullible Indians during the war years, which were mere kaagaz ke phool (paper flowers) with no khushboo (fragrance) even for namesake. The poem ends with a fervent plea that the people of Hind should not be taken in by the sorcery of the reforms.

Ai Hindi saada dil khabardar

Hargiz na chale tujh pe jadu

ya paayega khaak phir jab inse

Iss waqt bhi kuchh na le saka tu

(O simple people of Hind beware

Don’t let this spell work on you

If you couldn’t couldn’t take anything from them now

You’re not likely to get anything at all)

Josh Malihabadi who acquired his moniker of the shair-e- inquilab or the ‘revolutionary poet’ during the war period, talks with vim and vigour of the revolution that is nigh, a revolution that will shake the foundations of the British empire in his Shikast-e Zindaan ka Khwaab (‘The Dream of a Defeated Prison’:

Kya Hind ka zindaan kaanp raha hai guunj rahi hain takbiren

Uktae hain shayad kuchh qaidi aur torh rahe hain zanjiren

Divaron ke niche aa aa kar yuun jama hue hain zindani

(How the prison of Hind is trembling and the cries of God’s greatness are echoing

Perhaps some prisoners have got fed up and are breaking their chains

The prisoners have gathered beneath the walls of the prisons)

Satire, Pain and Passion Punctuate These Poems

The ever-doubting, satirical voice of Akbar Allahabadi— a long- time critic of colonial rule and a newfound admirer of Gandhi, shows us the great inescapable link between commerce and empire that Tagore too had alluded to:

Cheezein woh hain jo banein Europe mein

Baat woh hai jo Pioneer mein chhapey…

Europe mein hai jo jung ki quwwat barhi huwi

Lekin fuzoon hai uss se tijarat barhi huwi

Mumkin nahin laga sakein woh tope har jagah

Dekho magar Pears ka hai soap har jagah

(Real goods are those that are made in Europe

Real matter is that which is printed in the Pioneer…

Though Europe has great capability to do war

Greater still is her power to do business

They cannot install a canon everywhere

But the soap made by Pears is everywhere)

The great visionary poet Iqbal, who is at his most active, most powerful during these years, does not make direct references to actual events in the war arena;

nevertheless, he is asking Indians to be careful, to heed the signs in Tasveer-e Dard (‘A Picture of Pain’):

Watan ki fikr kar nadan musibat aane waali hai

Tiri barbadiyon ke mashvare hain asmanon mein

(Worry for your homeland, O innocents, trouble is brewing

The portents of disaster awaiting you are written in the skies.)

Adopting a fake admiring tone, Ahmaq Phaphoondvi seems to be praising the sharpness of the British brain in Angrezi Zehn ki ki Tezi (‘The Cleverness of the English Mind’) when he’s actually warning his readers of the perils of being divided while the British lord over them.

Kis tarah bapa hoon hangama aapas mein ho kyun kar khunaraizi

Hai khatam unhein schemon main angrezi zehn ki sab tezi

Ye qatl-o khoon ye jung-o jadal, ye zor-o sitam ye bajuz-o hasad

Baquii hii raheinge mulk mein sab, baqui hai agar raj angrezi

(Look at the turmoil and the bloodshed among our people

The cleverness of the English mind is used up in all such schemes

This murder ’n mayhem, wars ’n battles, cruelties ’n malice

The country’s garden is barren, with nothing but dust and desolation)

Towards Freedom and Fervour..

Zafar Ali Khan sounds an early, and as it turns out in the face of the British going back on their promise of self-governance, entirely premature bugle of freedom. While warning his fellow Indians to change with the changing winds that are blowing across the country as the war drags to an end, he’s also pointing our attention to the ‘Toadies’, a dreaded word for the subservient Indians who will gladly accept any crumbs by way of reforms in his poem Azaadi ka Bigul (‘The Bugle of Freedom’):

Bartania ki meiz se kuchh reze gire hain

Ai toadiyon chunne tum innhe peet ke bal jao

(Some crumbs have fallen from the table of Britannia

O Toadies, go crawling on your bellies to pick them)

In the end, there’s Agha Hashar Kashmiri who, in a sarcastic ode to Europe called Shukriya Europe, thanks it for turning the world into a matamkhana (mourning chamber), and for having successfully transformed the east into an example of hell.

Utth raha hai shor gham khakistar paamaal se

Keh raha hai Asia ro kar zaban-e haal se

Bar mazar-e ma ghariban ne chiraghe ne gule

Ne pare parwane sozo ne sada-e bulbule

(A shout is rising from the dust of the downtrodden

Asia is crying out and telling the world at large

On my poor grave there are neither lamps nor flowers

And not the wing of the moth or the sad song of the nightingale.)

(Rakhshanda Jalil is a writer, translator and literary historian. She writes on literature, culture and society. She runs Hindustani Awaaz, an organisation devoted to the popularisation of Urdu literature. She tweets at @RakshandaJalil

This is an opinion piece and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)

source: http://www.thequint.com / The Quint / Home> Voices> Opinion / by Rakshanda Jalil / November 11th, 2022