NEW DELHI :

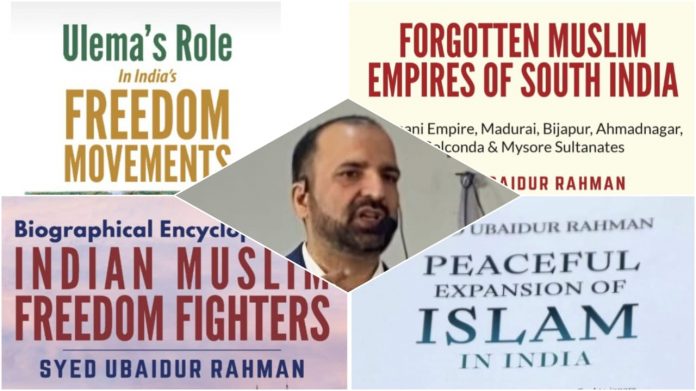

Syed Ubaidur Rahman, a Delhi based historian and author, has been single-handedly trying to resurrect Indian Muslim history over the past decade. He is a man with a mission, and that mission is to preserve the Indian Muslim history.

Over the past ten years, he has authored at least six books on medieval Indian history dealing with different aspects of the history. His books include, ‘Biographical Encyclopedia of Indian Muslim Freedom Fighters’, ‘Forgotten Muslim Empires of South India’, ‘Ulema’s Role in India’s Freedom Movement’ and his recently published book ‘Peaceful Expansion of Islam in India’. The latest book has become a talking point across India and beyond, as it debunks the fallacious notion of forced conversion of the local population to Islam. He proves, through meticulous research, that Islam came to South India, much before its arrival in the North and spread thanks to the efforts of Arab and Persian merchants besides Sufis who came in large number and settled throughout India.

Moin Qazi, while discussing the work of Syed Ubaidur Rahman, in his detailed essay in Transcend says, “A Muslim historian Syed Ubaidur Rhahman has brought a new secular perspective that presents the Muslim view boldly…He is the right person with the zeal and appetite to resurrect the vast culture of the South. His research will undoubtedly help in redefining the landscape of Muslim history. It is a tenacious task, but Ubaidur Rahman is a scholar of deep commitment to the cause”.

In order to create awareness about the Muslim history of India, Syed now offers at least three courses on different aspects of medieval and late medieval history of India, particularly the period dealing with the Muslim rule in Delhi and different parts of the country. His ‘3-month course on Indian Muslim History’ begins with the arrival of Islam and the conquest of Sind by Muhammad bin Qasim, followed by Mahmud of Ghazni and his conquests, Muhammad of Ghur and the establishment of Delhi Sultanate. It deals with different dynasties of the Delhi Sultanate and the spread of Islamic rule to South India during Alauddin Khalji and Muhammad bin Tughluq.

This course also covers Mughal rule as well as different Muslim ruling dynasties in Kashmir, Bengal, Malwa, Khandesh, Gujarat, Sharqis of Jaunpur, Bahmanis of Gulbarga/Bidar, the successor Deccani Sultanates of Ahmadnagar, Bijapur and Golconda as well as Nizam of Hyderabad and Mysore Sultanate of Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan. This course, that is covered in 24 sessions and conducted on Zoom, attracts participants from around the world.

He also runs another month long (8 session) course focusing on South Indian Muslim History. The history of South Indian Muslims has been completely ignored by both the historians and the Muslim community, notwithstanding the fact that in much of the Deccan and South India, Bahmani Sultanate ruled for close to two hundred years. The successor Deccani Muslim states ruled for another 200 years and Muslim dynasties, including Nizams, Nawabs of Carnatic, Mysore Sultans, continued to rule the region for a very long time.

Syed has just introduced another course that deals with India’s freedom movement and Muslim role. This course covers Muslims’ extremely important role in India’s first war of independence of 1857 against the British colonial rule. Muslims played leadership role in it. It will also cover Moplah Revolt, Reshmi Rumal Tehrik, Naval Mutiny of 1946 and also discuss thousands of Muslim prisoners who were imprisoned in the feared Cellular Jail of Andaman and Nicobar, remembered by most people as Kala Pani.

When asked as to why he has launched such courses, 48-year old Delhi based Syed says, “as history is being re-written in the country, and medieval history dealing with the Muslim period is being slowly erased from course books, it was imperative to teach our young generation about our history and heritage and our great past.

Thankfully, as opposed to people’s disheartening views, the courses have gone on to become a huge hit with people from around the country and beyond trying to enroll for the three courses, alhamdulillah. I am surprised as reputed scholars, professors, experts of Persian and even Chagatai languages enroll in our course from around the world. I am sure these courses and related efforts will prove help bring about long-term change”.

***

(Syed Ubaidur Rahman can be reached at 91-9818327757. Email: syedurahman@gmail.com. He tweets at https://x.com/syedurahman)

source: http://www.muslimmirror.com / Muslim Mirror / Home> Indian Muslims> Interviews / by Special Correspondent / August 07th, 2024