ASSAM :

The young poet represents an unapologetic Miya voice, one that the state’s new chief minister has described as a threat to Assamese identity and culture.

In an act of poetic justice, the people of Chenga, a constituency in lower Assam, have sent AIUDF’s Ashraful Hussain, a young Miya poet, as their representative to the newly elected Assam assembly. He is only one of 126 MLAs but the significance of his presence is that he represents an unapologetic Miya voice — one that the state’s new chief minister Himanta Biswa Sarma has declared as a threat to the Assamese identity and culture.

It has been said that the organisational skills of Sarma forced the BJP to prefer him as the new chief minister over the outgoing one but his brazen anti-Muslim and anti-Miya stance in the last five years can be a reason as well. He has openly said that his party did not want votes of the Miya Muslim community and that he wanted another NRC to identify these “outsiders”.

Ashraful Hussain’s victory has to be understood in this context. The word “Miya” is a slur used to describe Muslims who migrated from East Bengal to Assam over several decades, starting from the 19th century, and who live on the Char Chaporis (shifting riverine islands) of Assam. But Ashraful and his fellow poets have reclaimed it and turned it into a badge of honour. A poem written in 2016 by Hafiz Ahmed, the president of the Char Chapori Sahitya Parishad, took Assam by storm and inspired fellow poets. He wrote, “Write down/I am a Miya/My serial number in the NRC is 200543/I have two children/Another is coming/Next summer. /Will you hate him/As you hate me?”

Younger voices like Ashraful Hussain found courage in these plain words of their elder. “Who are they? Why can’t they be allowed to speak and sing the way they do? Ashraful writes: “And though I was born in Assam and pride in/Calling myself an Assamese/The language doesn’t slide down my tongue/My father wears a blue-checked lungi/My mother wears a saree/My sister wears mekhela or churidar/And me, brother, I wear jeans pants.”

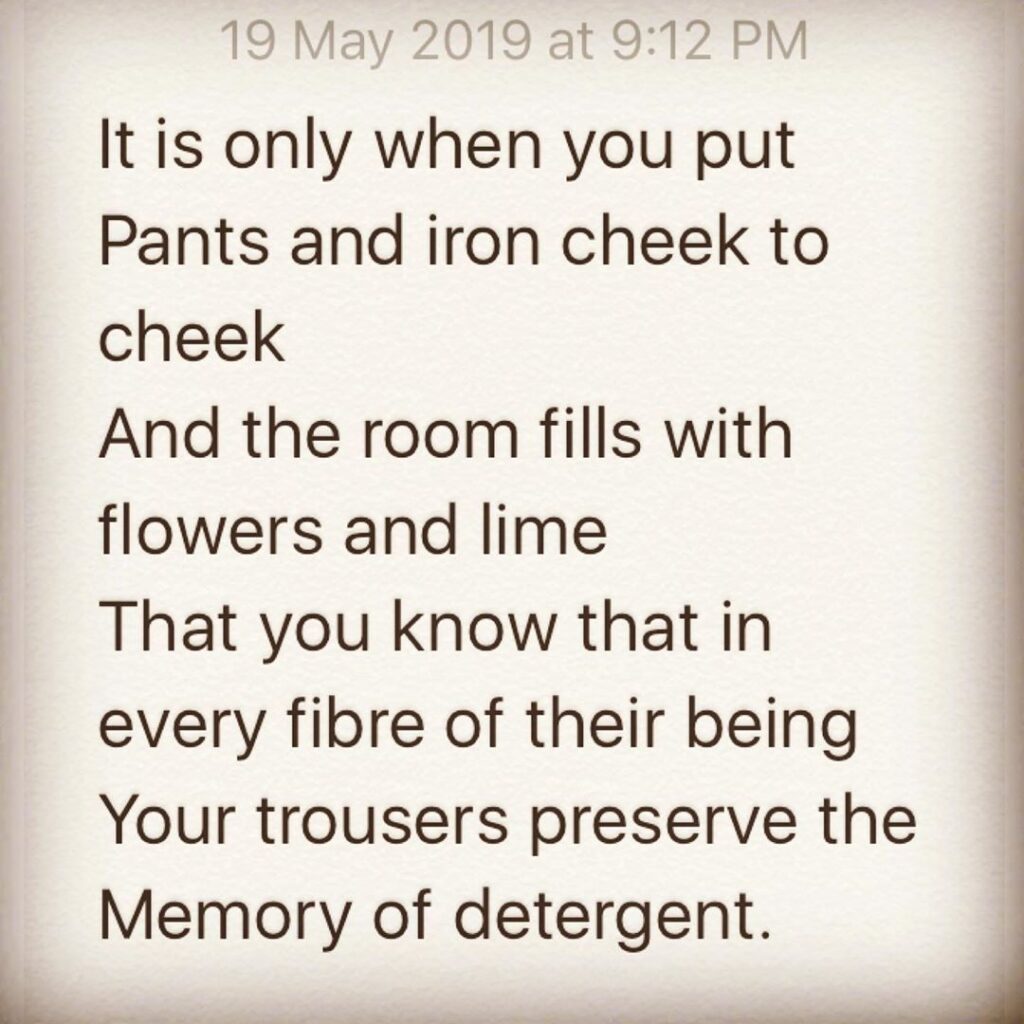

For this audacity to make themselves visible and lay a claim for a space in Assam’s cultural landscape, the Miya poets had to pay a price. In 2019, FIRs were lodged against them and they had to go into hiding. I recall a meeting at the Press Club in Delhi organised by the writers of Delhi in their support. Ashraful was supposed to read his poems there but he could not come.

These were the charges against them: The Miya poets were writing in an artificial language, there was nothing like a Miya dialect and they were fracturing the Assamese identity. The truth was that the Miya poets had broken the myth of one single Assamese voice. The people of the Char Chapori use dialects of Mymensingh, Pabna, Tangail, and Dhaka, regions now in Bangladesh, with the influence of Assamese as well as other local languages of Assam.

The question before the people Ashraful calls “choruwa, bhatiya, immigrant shaykh, neo-Asomiya, Mymensinghia” in one of his poems was to describe themselves. Who are they?

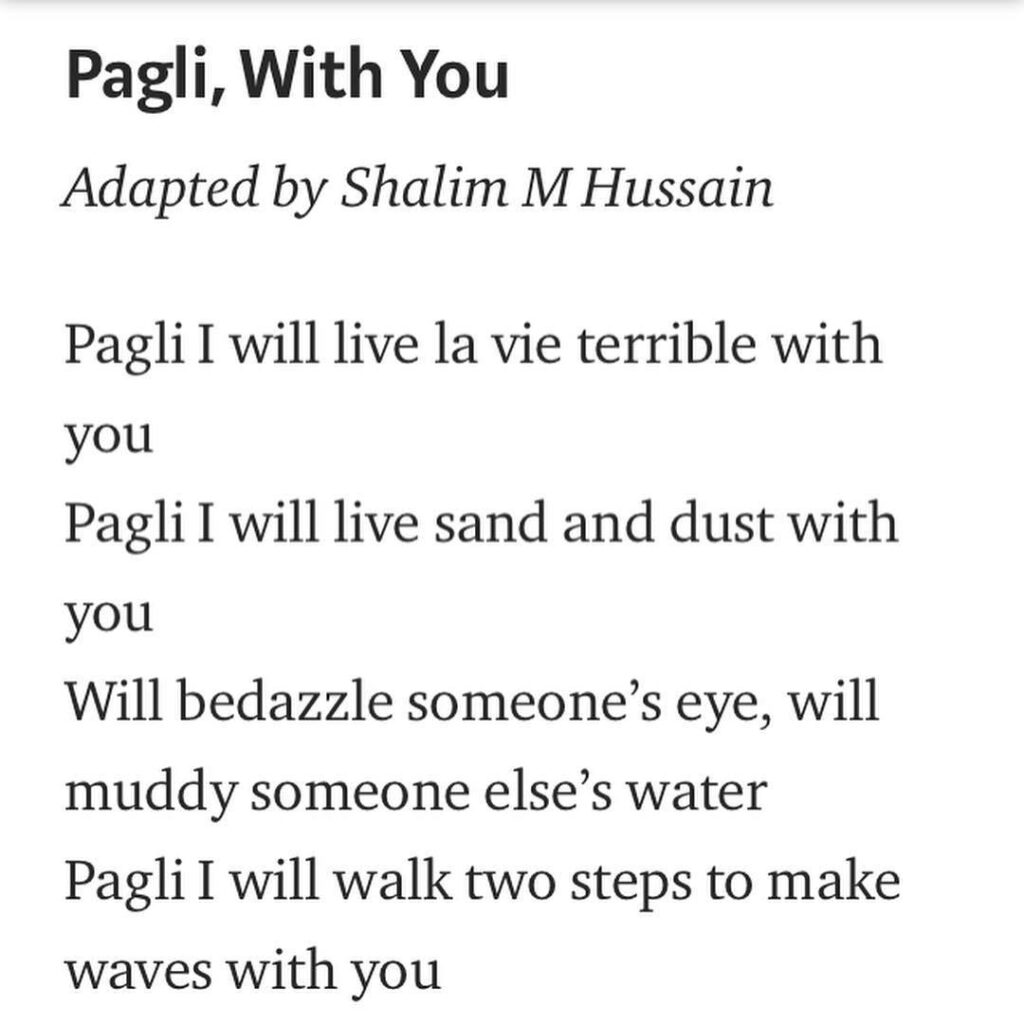

Shalim Hussain, a Miya poet, asked, “So what do we call ourselves then? If and only if it is impossible for us to be known simply as Indians or Assamese let us be called ‘Miya’. The difference between Miya and Bangladeshi must be clearly demarcated.” He explained, “… in Assam Miya is a derogatory term used for a specific community — Assamese Muslims of Bengal origin. ‘Miya’ is a matrix within which fall descendants of people who migrated from Tangail, Pabna, Mymensingh, Dhaka, and other districts of present-day Bangladesh. However, there is a class angle to the equation too. An educated Bengal-origin Assamese Muslim who also speaks Assamese might be able to camouflage his ‘Miyaness’. Since I am university educated and speak decent Assamese, I might not be called a Miya, at least until I make it explicit. My cousin, on the other hand, who drives a cycle-rickshaw in Guwahati, will always be one. My class privilege might protect me from the feelings of disgust reserved for my cousin.”

So, it was not for a literary career but to identify with their lesser privileged brothers, who have to face this slur daily, that Ashraful and his colleagues decided to call their poetry Miya poetry.

Ashraful is a soft-spoken, shy person but he has with great grit and determination stood for those who are threatened by the process of the NRC. His poetry gave voice to his people but in the real world of democracy, they needed representation where it mattered. So, he decided to go to his people and ask them, “If he sings for them, can he also be given the authority to speak for them as their representative?” The people of Chenga overwhelmed him with their mandate. A greenhorn in politics, he defeated AGP’s Rabiul Hussain and Sukur Ali Ahmed, a longtime sitting Congress MLA, by more than 50,000 votes.

In the assembly, he will take oath as the representative of his people after the man who wants them disenfranchised takes oath as the Chief Minister. Ashraful Hussain will have the company of his poetry to respond to the violent politics of erasure: “I have grown a bud and two leaves on my hands/I have learnt to write two lines/I have learnt to open my mouth and say/… In the name of my mother who died/In a detention camp, I swear/That this voice in my throat will grow louder/And some day rustle the folds in your ears. /I swear sir, I swear by my dead mother.”

Let us thank the people of Chenga and celebrate this vote for Miya poetry.

source: http://www.indianexpress.com / The Indian Express / Home> Opinion> Columns / by Apoorvanand / May 13th, 2021