INDIA :

Were the Mughals the most literary dynasty that ever ruled India?

The Mughals have garnered many adjectives over the centuries. Once, when the world looked in awe at the power and wealth of Hindustan, they were simply ‘Great’. More recently, as Hindustan locks itself in a manic tussle with its past, they are ‘foreign’ or ‘invaders’, often both. Perhaps it’s time for a calming epithet: the Mughals were, without question, literary.

The first of them, Babur, is known for defeating Ibrahim Lodi in Panipat, but almost equally renowned for his autobiography. It’s not that kings hadn’t written before. Julius Caesar was composing accounts of his Gallic campaigns in 1 BC. The earliest autobiography — an account of a person’s life, not a record of events — was St. Augustine’s Confessions, written circa 400 AD. Babur, living a millennium later and a world away, invented the form for himself with Baburnama, the first personal memoir in Islamic literature. And he did it with flair — “both a Caesar and a Cervantes”, as Amitav Ghosh has described him — writing with lucid ease, whether of the pangs of his first love or his battle strategies. (The first autobiography in an Indian language, incidentally, may be Ardhakathanak (‘Half Life’) by Banarasidas, a Jain merchant who wrote in Braj Bhasha, and in verse, in the 17th century.)

The urge to write

In the centuries after Panipat, the Mughal empire grew into a global superpower, then shrunk to a wretched speck. The last Mughal ruled little besides the Red Fort, but he did preside over an efflorescence of Urdu poetry: Ghalib, Momin and Zauq shone bright in his court, and Bahadur Shah ‘Zafar’ was no mean poet himself. Imprisoned and exiled after the Uprising of 1857, the frail emperor would write Na wo taj hai na wo takht hai, na wo shah hai na dayar hai (‘No crown remains no throne remains, neither ruler nor realm remains’). The urge to write, however, that remained: Bahadur Shah is said to have etched his verses on the walls of his prison, with charcoal, when he was denied paper and pen.

Babur may not have been entirely displeased. In a letter to his son, Humayun, Babur offers equally urgent advice on how to rule and how to write. The unfortunate Humayun is ticked off on both counts: his desire for solitude is “a fatal flaw in kingship”, and his prose is convoluted. “Who has ever heard of prose designed to be an enigma?” writes Babur, exasperated. Humayun must write, instead, “with uncomplicated, clear, and plain words”.

Father and son

Humayun was unable to meet his father’s exacting standards, both as ruler (he lost the fledgling empire) and as writer (even if he did die in a library), but the literary gene stayed with the dynasty. It blossomed in Gulbadan, one of Babur’s daughters, who wrote the Humayun-nama; it gestated in Akbar, who was as famously illiterate as he was fond of commissioning histories and translations; and, most notably, it flowered in Jahangir, whose literary talents equalled, if not exceeded, his great-grandfather’s.

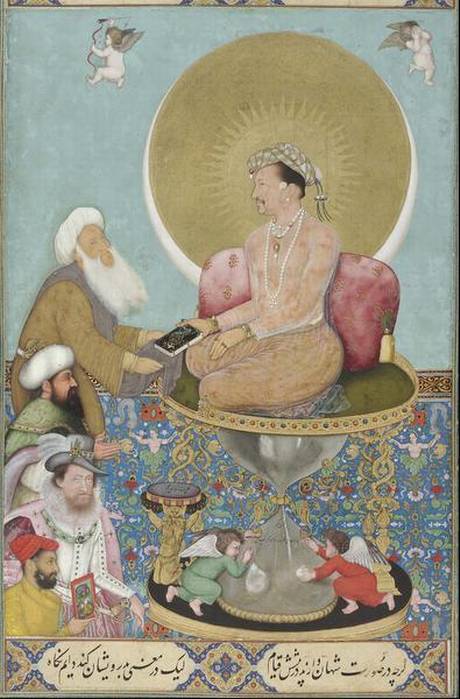

William M. Thackston, who has translated the Baburnama, admits that despite its many surprises and charms, the memoirs can sometimes lag a bit: the “reader may skip or skim at will”. The Jahangirnama, on the other hand, flows like a breeze — so much as to attract the criticism to which ‘popular’ writing is prone. Thackston, who has also translated the Jahangirnama, writes that while much of this work is “fascinating…for the general reader” much is also “of little or no historical significance”. Fun to read, that is, but inadequately serious. As Jahangir himself is often accused of being: lightweight.

Playful tone

It’s true enough that the Jahangirnama is marked by a sometimes startling whimsy. Once, marching with his nobility along a rivulet, its banks overgrown with oleanders, Jahangir had them all arrange the blossoms on their turbans so that “an amazing field of flowers was… made!” Another time, having caught a dozen-odd fish, Jahangir released them all with pearls pinned to their noses. Even when he is writing of seemingly sober matters, Jahangir can’t help a certain playfulness.

Near the beginning of the book, for example, Jahangir lists a set of decrees that he issued when he became emperor. Among these worthy orders — abolishing certain taxes and punishments, building wells and hospitals — was one that banned the manufacture and sale of alcohol.

Here, however, Jahangir adds a caveat: he has been drinking — and has often been drunk — since he was 18. Later, he offers a detailed account of his alcoholism and de-addiction (his hands shook so much, others poured the liquor down his throat; a doctor told him he wouldn’t last six months; he diluted his arrack with wine and raised his spirits with opium) — a remarkable confession made even more so by the fact that Jahangir makes it immediately after describing the “great persistence” it took for him to get his son, Shahjahan, to down a birthday drink.

A drinking problem is not all the emperor disclosed. The Jahangirnama also contains a frank account of murder; or, at least, an order to murder, which led to the ambush and assassination of Akbar’s friend and biographer, Abu’l Fazl.

Murder most murky

The plot is murky and tangled, but in brief it was thus: as prince, Jahangir felt threatened by Abu’l Fazl’s influence over the emperor, Akbar, and so had him killed. It was a ruthless decision, and reveals a man of steely ambition under the drunken haze and oleander blossoms.

It’s an ambition that’s often overshadowed by Jahangir’s acute sense of beauty and delight in nature. He could describe the weather such that you can feel it, “the air was so fine, a patch of cloud was screening the light and heat of the sun, and a gentle rain was falling”. Spring flowers in Kashmir would make his heart “burst into blossom”.

Among the best-known passages in the Jahangirnama are those about the mating, nesting and eventual parenthood of Jahangir’s pet saras cranes, Laila and Majnu. So intense is his joy in their rituals — “I immediately ran out to watch” he writes of the dawn on which they mated; then of how Majnu would guard his mate all night, and scratch her back with his beak at dawn to relieve her of nesting duties — that one gets the sense Jahangir would have sat on those eggs himself, if he could.

Writers’ prerogative

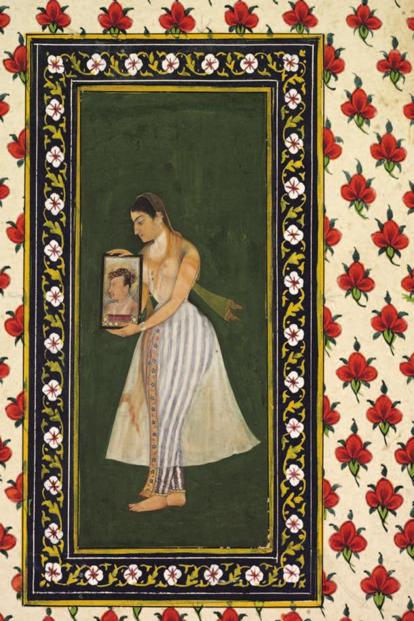

It’s passages like this that prompted Henry Beveridge, editor of a 19th-century translation of the Jahangirnama, to declare that Jahangir would have been a “better and happier man” as the “head of a Natural History Museum”. And yet, would the head of a museum have commissioned the painting of Inayat Khan? This, too, is a story in the Jahangirnama. A hard-drinking nobleman appeared before Jahangir, asking for sick leave.

Inayat Khan was emaciated beyond belief. “How can a human being remain alive in this shape?” the emperor exclaimed. Jahangir let Inayat Khan go home, gave him a generous grant, but also, he summoned his painters. Like the extinct dodo, of which Jahangir’s atelier has produced the most authentic record, so the painters now created a terribly vivid portrait of a dying man.

Such single-mindedness is, of course, the prerogative of emperors — and also, perhaps, of writers. Both to rule and to narrate requires a certain distance, even coldness. In fact, of late, Jahangir’s writings, and therefore his rule, are being re-evaluated.

The historian Corinne Lefèvre, for example, does not read the Jahangirnama as a record of imperial fancies, but finds it “a masterpiece of… imperial propaganda”. Jahangir himself suggested as much when he ordered copies of his book sent to other kings as a “manual for ruling”.

Unlike his father, Jahangir did not create the intricate foundations of a nation-state. Unlike his son, Jahangir did not build the Taj Mahal. No lasting administrative reforms, no carved blocks of marble, it’s a book that Jahangir left us to read. Just words.

No wonder he’s so open to interpretation.

The writer’s most recent book is Jahangir: An Intimate Portrait of a Great Mughal.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Books – The Lead / by Parvati Sharma / November 09th, 2018