DELHI :

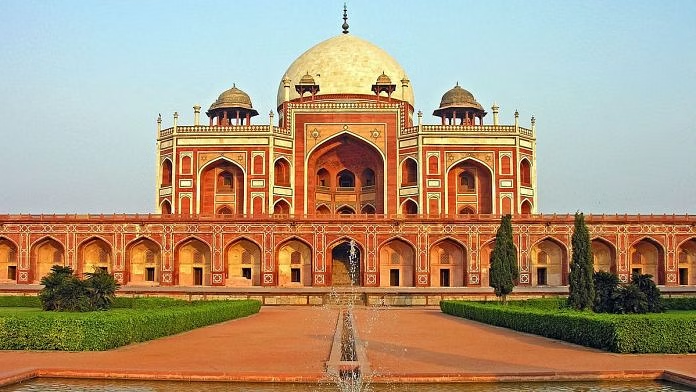

Humayun’s Tomb introduced India to the Persian style of a domed mausoleum set in the centre of a landscaped char-bagh garden.

Humayun’s Tomb, Delhi | Photo: Commons

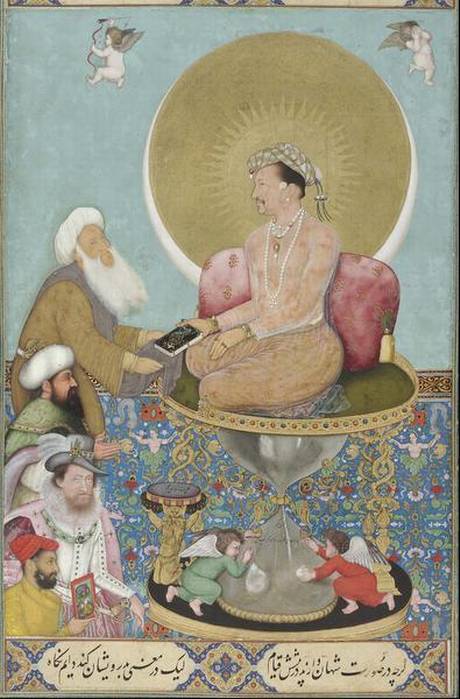

Humayun’s first wife was a Persian from Khorasan and a daughter of Humayun’s maternal uncle. She was also called Haji Begum, probably because she had gone on the Haj to Mecca. During Humayun’s reign, she appears in history at the Battle of Chausa, where the harem was captured by Sher Khan. In all the chaos of battle, a boat carrying women capsized and her young daughter, Aqiqa Begum, was drowned. Bega Begum did not have any more children. Today she is remembered for the tomb of Humayun that she built in Delhi. After the death of her husband, when she decided to build the mausoleum, she was encouraged in her endeavour by her stepson Akbar, who was very fond of her.

Among all Humayun’s wives, Bega Begum lived a life of surprising independence. She went off to the Haj and came back with Arab craftsmen who worked at the tomb. This was much before Gulbadan Begum and Hamida Banu Begum went to Mecca during the reign of Akbar, their trip getting much more coverage in contemporary writing. Bega Begum did not join the harem in Agra but remained in Delhi, supervising the building work. An episode described by Gulbadan shows that she was a spirited woman who even spoke sharply to her husband when he did not visit her.

Among all Humayun’s wives, Bega Begum lived a life of surprising independence. She went off to the Haj and came back with Arab craftsmen who worked at the tomb. This was much before Gulbadan Begum and Hamida Banu Begum went to Mecca during the reign of Akbar, their trip getting much more coverage in contemporary writing. Bega Begum did not join the harem in Agra but remained in Delhi, supervising the building work. An episode described by Gulbadan shows that she was a spirited woman who even spoke sharply to her husband when he did not visit her.

Then Humayun replied, ‘It is a necessity laid on me to make them happy. Nevertheless, I am ashamed before them because I see them so rarely… I am an opium-eater. If there should be any delay in my comings and goings, do not be angry with me.’ However, Bega Begum was not reassured and said, ‘Your Majesty has carried matters to this point! What remedy have we? You are emperor. The excuse looked worse than the fault.’ Gulbadan ends her tale saying, ‘He made it up with her also.’

The contemporary historian Badauni writes that Akbar and Bega Begum were very close and he describes her as a ‘second mother to Akbar’. Once when the boy Akbar had a toothache, Bega Begum brought some medicine but Hamida was reluctant to give it to him. This was understandable since, in a harem that was often full of politics and jealousy, the mothers feared that their children could be poisoned. Abul Fazl quotes Akbar as saying, ‘As she knew what the state of feeling was, she [Bega Begum] in her love to me swallowed some of it without there being any order to that effect, and then rubbed the medicine on my teeth.’

Bega Begum would often travel to Agra to meet Akbar and she spent her allowance doing charity. The Jesuit Antoine de Monserrate wrote, with reluctant approval, of her good works, ‘Throughout her widowhood she devoted herself to prayer and to alms-giving. Indeed, she maintained five hundred poor people by her alms. Had she only been a Christian, hers would have been the life of a heroine.’

Bega Begum was the first of the Mughal women to become a builder, and many would follow to build mausoleums, mosques, madrasas, seminaries, bazaars and gardens. Humayun’s Tomb introduced India to the Persian style of a domed mausoleum set in the centre of a landscaped char-bagh garden, which would reach its peak with the Taj Mahal. Built near the dargah (mausoleum) of the Sufi saint Sheikh Nizamuddin Auliya, the mausoleum complex became the graveyard for many members of the dynasty. Bega Begum is buried in the mausoleum near her husband, and somewhere nearby is the grave of one of the most unfortunate princes of the dynasty – Dara Shukoh.

___________________________

This excerpt from Mahal: Power and Pageantry in the Mughal Harem by Subhadra Sen Gupta has been published with permission from Hachette India. Hardback Rs 599.

_______________

source: http://www.theprint.in / The Print / Home> Page Turner> Book Excerpts / by Subhadra Sen Gupta / November 30th, 2019