NEW DELHI :

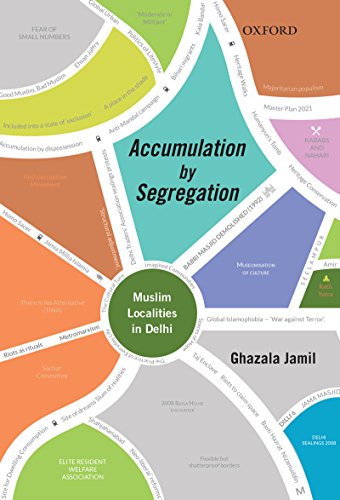

Accumulation by Segregation by Ghazala Jamil / India, OUP India, 2017 / 244 pages / ISBN: 9780199470655/750 INR

Muslims in India continue to live in precarious conditions. Being classified as a minority implies more than just their small numbers; historically, it has implied a completely varied identity, negatively affecting their political, social, or cultural lives. With complete disregard for the geographical and cultural diversity within the Muslim community, postcolonial Muslims in India are differentiated by their aspersed identity. Within this overall restriction, which frequently took violent turns and formed the circumstances for surviving, Muslims had to negotiate their citizenship. Muslims’ circumstances were affected by their humiliating, dehumanising, and stereotypical identity.

Seen in this light, this book by Ghazala Jamil is an intervention into the conditions of Muslims in Delhi, studied as a part of the globalisation process. It provides readers with a systematic way of looking at the segregation of Muslims in Delhi. It looks at segregation in the context of the 1857 mutiny, the partition of 1947, Emergency and communal violence, and examines the relationship between globalization and segregation. It also examines the discursive practices perpetuating and strengthening the Muslim identity as anti-modern, backward, and unchangeable, thereby hindering the developmental potential among Muslims.

The author argues that comparing the historical ghettos of the Jewish population in Europe to the concentration of Muslims is misleading. The situation of Muslims is not primarily caused by coercion, violence, and oppression but rather by the limited options they face. This makes their situation historically specific and functionally distinct, warranting critical examination.

The book largely focuses on areas in Delhi, including parts of the walled city and localities outside Shahjahanabad; Seelampur and other trans-Yamuna Muslim areas in North Eastern Delhi. It also includes Jamia Nagar in South Delhi; Nizamuddin and Nizamuddin West, and the Taj Enclave. Through ethnographic explorations, Jamil explores the city’s inhabitants’ memories, living experiences, dreams, and discontent.

Violence, displacement, discrimination, migration and hope remain common in making these settlements. Various events, such as post-partition violence, the beautification drive during the emergency, and subsequent violence associated with growing Hindu nationalism, particularly in Gujarat, have contributed to the establishment of these settlements. As a result, a large influx of people migrated to settle in Delhi. By the late 1980s, segregation in Delhi on religious identity lines became almost final and complete (p. 5). These settlements faced various forms of discrimination, including being labelled as centres of terrorism, poverty, backwardness, and fanaticism associated with Muslims.

These places are identified as Muslim settlements and are subsequently termed ‘mini-Pakistan’, as with Seelampur. These conditions further determine the relationship of Muslim settlers beyond the segregated areas.

In the context of economic liberalisation, Delhi provided a sense of security in segregation but also better educational and economic opportunities to Muslims. Capitalism is found in Muslims as an ‘incarcerated resource’. For example, in Jamia Nagar, students with the requisite skills are making their place in the global economy. In Seelampur, the small manufacturers, both semi-skilled and unskilled labourers have ‘benefited’ from manufacturing jobs brought to India by globalization. But what is making them functionally distinct and incarcerated resources from other beneficiaries is that their involvement with globalization is restricted by their location in the segregated areas, which limits their movement and confines them to these areas only. Globalization, in this case, is not promoting progress but rather enforcing separation and discrimination, creating barriers that are challenging for Muslims to overcome.

Muslims are incorporated into the capitalist objective of maximizing profits. However, their situation is distinct due to several limitations. Firstly, they receive less financial help from banks and lack capital, both socially and financially. Additionally, they face a disproving work and business environment. Moreover, they are often viewed as enemies, backward, stagnant, and traitors. These factors ultimately determine their terms of incorporation with the outside world. Hence, making the point that aspersed identity has a distinctly exploitative and material function.

Despite segregation, the real estate business thrives within these settlements while keeping the segregated topography of Delhi undisturbed. Within these processes Muslim neighbourhoods have become complex and diverse in economic classes. Zakir Nagar Extension, Jogabai Extension, Johri Farm and Taj enclaves have emerged as affluent enclaves, areas of the neighbourhood where the wealthy citizens are clustered. Despite being wealthy, the residents are unable to leave their neighbourhood because Hindu property owners in other sections of the city refuse to sell or rent their homes to Muslims or because they see a threat of violence or claim to have had already experienced it. They try to enclose themselves and try to become less like the popular stereotypes about Muslims.

The author argues further that old Delhi, Jama Masjid with adjoining areas and that of Nizamuddin fell prey to commodification from the 1990s. The less significant structures, the Partition’s history and legacy, the clothing, the eateries, and the fragrances all serve as living artefacts and installations for tourists in addition to the historical monuments and religious sites in the region. The taboo topics of Muslims and “Muslimness” have evolved into odd, even weird, spectacles for the adventurous.

People flock to the streets of old Delhi to explore the exotic and the antique, reducing the inhabitants to spectacular displays for the consumer while rendering political contestation and mobilization difficult (p. 91). Through accumulation, it functions as a means of constructing the identity of individuals, connecting them to a particular place and creating an impression of an inherent and unchanging nature.

Jamil notes that in this effort of commodification, the state, civil society, and media are all involved, promoting history tours and good exotic Muslim foods to tourists. Keeping these things in mind, marketable Muslims in segregated areas has to remain as it is for the consumption of others.

Ghazala Jamil, drawing from Althusser, argues on the same lines that ideological state apparatus is reflected in cinema and media representation. She argues that Muslims and Muslimness are always shown and understood as homogenous entities, with utter disregard for their variation in political interest and in cultural practices. This notion is sustained and perpetuated in popular media films. Where the lines between reality and the stage are blurred. The author here analyses various Hindi movies during the period between 2008 to 2010, where the popular image of Muslims depicted as fundamentalist, parochial and backwards was given a space and subsequently uncritically consumed by viewers. When examining print media descriptions, it is evident that irrational attitudes, dangerous behaviour, volatility, and backwardness continue to be prominently used to portray incidents involving Muslims, often generalising the entire community.

Further, framing her case through fake encounters, extra-judicial killing, and differential treatment, she claims the Indian Muslim is fashioned as homines sacri. They are being made to “feel guilty for the partition of the country, represented as irrational fundamentalist fiends, loathsome and polluted, disloyal normative non-citizens, and potentially dangerous terrorists”(p. 99).

Homines sacri, according to Trevor Parfitt (2009), are individuals who have been placed outside the boundaries of the law, rendering them outlaws. They can be harmed or even killed without any legal repercussions. Their lives are meticulously planned, controlled, and regulated in every possible aspect.

When employing the concept of ‘homo sacer’ for Muslims in India, akin to its application to Jews in concentration camps, it raises the question of how to interpret the legal constitutional rights granted to Muslims in comparison to the rights that Jews were deprived of. This brings to light the inquiry as to how the treatment of the Muslim case, which Jamil considers “historically specific and functionally distinct,” falls short in addressing this issue.

The author puts forth a convincing viewpoint concerning the Muslim community’s struggle with a deficit in citizenship and a feeling of alienation within the political sphere. This argument carries logical weight as it emphasizes the obstacles faced by Muslims in fully exercising their rights as citizens and achieving a sense of inclusion within the larger political framework.

Particularly since the rise of right-wing governments, hatred against Muslims has become more crude and naked; where everything associated with Muslims is being politicized and then criminalized. Every activity in the eyes of sponsored vigilantes has become some or other kind of jihad against the government and the people. Responses from the government include intimidation, demolitions, and arrests of victims guised as perpetrators. With the unfolding of these events, experts are even raising concerns over the situation and its striking similarity with past historical atrocities.

However, this violence is not absolute. The Muslim remains an equal citizen theoretically capable of posing counter-hegemonic discourse, which the author does acknowledge. Therefore, it is crucial to approach the situation of Muslims with an understanding that their experiences, though marked by violence, do not reduce them to the status of ‘homo sacer’, as they retain the capacity for political agency and the ability to contest dominant narratives.

The author in the end puts her hope in education and the growing enthusiasm around it among Muslims. Muslims themselves are expected to make interventions in their own circumstances and discourses around them. For instance, measures to combat epistemic Islamophobia would also require adjustments in other areas. This can be found in the ‘Discursive-Political’, which encompasses manifestations of daily life, culture, and behaviour and are primarily considered non-political. These activities, as she claims, involve transformative political practices that reveal the ‘contingent and socially constructed’ nature of what is portrayed as ‘necessary and natural’. The effective resistance for her is to claim and assert citizenship and be able to represent and define rather than getting defined.

References

Parfitt, Trevor. (2009). Are the Third World Poor Homines Sacri? Biopolitics, Sovereignty, and Development. Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Jan.-Mar. 2009), pp. 41-58.

source: http://www.thedaak.in / The Daak / Home> Issue No.4 / by Rizwan Hamid / July 15th, 2023