Hyderabad, TELANGANA :

Rainbow Peacock Marbled Paper (source: The Whimsical Marbler)

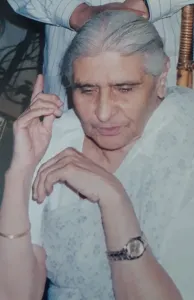

Fatima Alam Ali (1923-2020) was a writer of pen portraits (khaake) and humorous essays (tanz-o-mizah) from Hyderabad. Her work offers an untapped and intimate glimpse into the literary personalities and gatherings that flourished in mid-twentieth century Hyderabad.

Fatima Alam Ali (Source: Asma Burney)

Surprisingly, her writing has not received the proper attention it deserves. This can be attributed to the general neglect of the pen-portrait and non-fiction writing in general in the study of Urdu literature. Most scholarly work and translation has focused on poetry and fiction. However, her work is also neglected, in part due to the triple marginalization that women writers from Hyderabad face—as women, as citizens of a former princely state, and as Urdu writers from the Deccan.

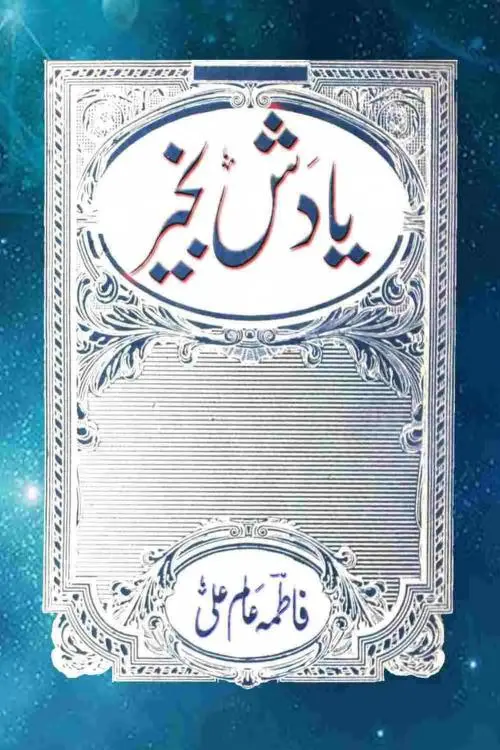

Yaadash Bakhaer by Fatima Alam Ali (Source: Archive.org)

Fatima first began writing at school in Lucknow at the behest of Urdu teacher and writer Razia Sajjad Zaheer. She was later encouraged to continue by Jahanbano Naqvi, another Urdu teacher and writer, when she was at Women’s College (Osmania University) in Hyderabad in the 1940s. Nurtured by a network of women writers, Fatima published widely in newspapers, magazines, and books while also reading her work on All-India Radio and at literary gatherings. In 1989, a collection of her pen-portraits and humorous essays were compiled in a book called Yaadash Bakhaer (“May God Preserve Them”). This text is a rich storehouse of information and insight into contemporary figures living in Hyderabad as well as the reflections of a woman writer coming into her own.

Fatima was the daughter of one of the great Urdu luminaries of the mid-twentieth century, Progressive writer and journalist Qazi Abdul Ghaffar (1889-1956). He began the influential left-wing newspaper Payaam in Hyderabad. Her cheerful and lively personality notwithstanding, Fatima mentions how she felt not only gratitude but also a sense of anxiety about this connection.

Interactions with her father’s peers and members of the Progressive Writers movement were always burdened by the awareness that she was Qazi Sahab’s daughter. She believed that she was respected because of her relationship to Qazi Sahab and not the merit of her own achievements. This left Fatima’s writing dotted with self-deprecating and apologetic comments that gesture towards a certain “anxiety of authorship.” The gendered aspect of this anxiety has been explored by Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar in the context of Victorian Women’s writing.

One place this anxiety of authorship appears in Fatima’s work is a long disclaimer she gives about her perceived inability to write about her father. She appeals to her readers that if they do not like her pen-portrait of him, they should forgive her, and if they do like it, then they should attribute it to the “noorani faiz” (luminous grace) of her father. Such prefacing apologies are part of established convention in Urdu and Persianate prose genres (such as the biographical tazkira). However, with women writers, they can be additionally tinged with gendered anxieties stemming from durable patriarchal norms and values.

Fatima’s pen-portraits draw attention to many contemporary Hyderabadi authors. Her portraits bring to life luminaries such as the writer and scholar Agha Hyder Hasan, an old Aligarh connection and dear friend of her father’s, and the scholar Habib ur-Rehman. We also see through her eyes her childhood playmate Ainee, who met her unchanged and with the same affection after a meteoric rise in the literary firmament as Qurratulain Hyder. She remembers Razia Sajjad Zaheer – “a woman in a man’s world” – as a mesmerizing teacher, hardworking mother, talented writer, and maternal figure. Fatima, whose own mother had died soon after her birth, remembers Razia with great emotion and is unable to find the words to describe the love she had given her.

Fatima grew up being mothered by the father figures in her life, an analogy she frequently draws. She describes her unusual and lively relationships with these men, who included, besides her father, her maternal uncles, Agha (whom she called “Chacha”), Habib ur-Rehman (“Baba”), and even Makhdoom Mohiuddin. With Qazi Sahab and Agha, the teenaged Fatima had relationships that were akin to friendships, marked by banter that was strangely grown-up. This was frowned upon in a conservative society that still believed in upholding a certain image of older men as abstract figures demanding veneration and formal distance. Fatima’s banter included teasing her father about the women who would fall for his dashing good looks and jokes with Agha Chacha about her future marriage.

It is not surprising, then, to locate the sense of ease with which Fatima writes and remembers the towering male literary figures of her youth. She writes fluidly and eloquently about them and with the same comfort and affection as she does about Razia Sajjad Zaheer or Zeenath Sajida.

Of particular interest and value in this regard is a memorable essay called “Adabi Mehfil” (“Literary Gathering”) that Fatima wrote – decades later – about an all-male mushaira that was hosted at Qazi Sahab’s home when the Progressive Writers’ Conference took place in 1945. Those who attended included Agha, Makhdoom, Jigar Moradabadi, Fazlur Rehman, Sikandar Ali Wajd, Hosh Bilgrami, Kaifi Azmi, Majrooh Sultanpuri, Ali Sardar Jafri, Ghulam Rabbani Taabaan, Sahir Ludhianvi, and Srinivas Lahoti.

Qazi Sahab could not afford the arrangements that were made in aristocratic homes, so they had only a buffet table under the open night-sky. There were no huqqas, only cigarettes, and the sole accessory demonstrating any continuity from an older tradition of mushaira was the paan that was arranged carefully and offered from a khaasdaan.

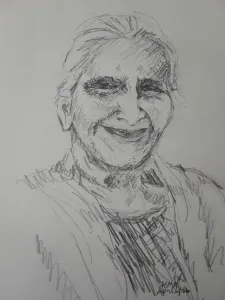

Fatima Alam Ali (Source: Asma Burney)

In engaging detail, Fatima introduces us to the august personalities of poets, writers, and intellectuals, as they dine with friends and peers before the mushaira begins. It is in her astute, sympathetic observations of these quintessential performers over dinner that we see their human dimensions, somewhat stripped of the dazzle of celebrity. Indeed, small aspects of their personalities often form the most attractive and compelling features of Fatima’s writing. She explains how they spoke more than they ate, how Srinivas Lahoti took over as host and led people to the table, and how Agha Hyder Hasan, who was unaccustomed to the new culture of buffet dining, sat by himself on a chair and balanced his plate on his lap.

Yet, Fatima writes as much as a fan as the host of such a gathering. She tells us, for example, how she held her breath while Makhdoom recited, afraid to disturb even the air around him. In vivid, engrossing detail, she recreates the charged atmosphere of the mushaira, where “in the Lakhnavi style,” everyone gives way to the others until Qazi Sahab intervenes and directs one of the younger poets to begin.

The euphoria when a striking verse is skillfully recited, the enthusiastic requests for certain well-known compositions, the restlessness when a particularly fraught verse is delivered, the unspoken code of hierarchy and ceremony, and even the specific verses that were produced – all these are represented in sparkling prose and bring the mushaira alive for the reader. What adds to the immediacy and vividness of her writing is that she addresses the reader periodically, saying “just look at this!” or “did you see that?,” transporting the reader to the time of imaginative reconstruction.

At the same time, Fatima does not shrink from criticizing these great men, telling us regretfully that the gifted ghazal proponent Majrooh Sultanpuri is now but a “filmi” poet or that Sahir Ludhianvi was already full of himself before he became famous. Through her sensitive, discerning descriptions of their appearance, temperament, and individual style of recitation, we get an intimate glimpse into their personalities: Majaaz, who was always shy when sober; sleepy, languid, dishevelled Kaifi, who always had a strange glitter in his eyes at mushairas; Jigar’s jaunty self and the errant wisp of hair that peeped flirtatiously from his cap; Sulaiman Areeb, who would cadge cigarettes from an indulgent Qazi Sahab, who in turn would sway in pleasure when Makhdoom sang his best verses; Makhdoom, the people’s poet, who would ask for achaar with his qorma and later be inundated with requests for his verses; and the evergreen wit and flamboyance of Agha, the quintessential Mughal from old Delhi.

Fatima Alam Ali (Artist and Source: Asma Burney)

In engaging detail, Fatima introduces us to the august personalities of poets, writers, and intellectuals, as they dine with friends and peers before the mushaira begins. It is in her astute, sympathetic observations of these quintessential performers over dinner that we see their human dimensions, somewhat stripped of the dazzle of celebrity. Indeed, small aspects of their personalities often form the most attractive and compelling features of Fatima’s writing. She explains how they spoke more than they ate, how Srinivas Lahoti took over as host and led people to the table, and how Agha Hyder Hasan, who was unaccustomed to the new culture of buffet dining, sat by himself on a chair and balanced his plate on his lap.

Yet, Fatima writes as much as a fan as the host of such a gathering. She tells us, for example, how she held her breath while Makhdoom recited, afraid to disturb even the air around him. In vivid, engrossing detail, she recreates the charged atmosphere of the mushaira, where “in the Lakhnavi style,” everyone gives way to the others until Qazi Sahab intervenes and directs one of the younger poets to begin.

The euphoria when a striking verse is skillfully recited, the enthusiastic requests for certain well-known compositions, the restlessness when a particularly fraught verse is delivered, the unspoken code of hierarchy and ceremony, and even the specific verses that were produced – all these are represented in sparkling prose and bring the mushaira alive for the reader. What adds to the immediacy and vividness of her writing is that she addresses the reader periodically, saying “just look at this!” or “did you see that?,” transporting the reader to the time of imaginative reconstruction.

At the same time, Fatima does not shrink from criticizing these great men, telling us regretfully that the gifted ghazal proponent Majrooh Sultanpuri is now but a “filmi” poet or that Sahir Ludhianvi was already full of himself before he became famous. Through her sensitive, discerning descriptions of their appearance, temperament, and individual style of recitation, we get an intimate glimpse into their personalities: Majaaz, who was always shy when sober; sleepy, languid, dishevelled Kaifi, who always had a strange glitter in his eyes at mushairas; Jigar’s jaunty self and the errant wisp of hair that peeped flirtatiously from his cap; Sulaiman Areeb, who would cadge cigarettes from an indulgent Qazi Sahab, who in turn would sway in pleasure when Makhdoom sang his best verses; Makhdoom, the people’s poet, who would ask for achaar with his qorma and later be inundated with requests for his verses; and the evergreen wit and flamboyance of Agha, the quintessential Mughal from old Delhi.

At the same time, she comments on the unreliability and instability of memory, cautioning us that time, place, and people are likely to get mixed up in her writing. And yet, she reveals an astonishing ability to reproduce verbatim specific verses or entire ghazals or nazms that were recited at literary gatherings. This signals how our memories operate, focusing on the enduring impression that certain events and experiences make on us, rather than external or superficial contexts.

Fatima’s pen-portraits are always coloured with expressions of nostalgia and loss and an urgency to record these figures, their work, and their milieu for posterity to ensure that they are not forgotten. In the process, she creates an important “memorative” collection that provides unique information, insight, and perspective upon a particularly important period in the history of Urdu literature.

source: http://www.maidaanam.com / Maidaanam.com / Home / by Nazia Akhtar / October 11th, 2011

By Nazia Akhtar. Nazia is Assistant Professor of Literature at the International Institute of Information Technology, Gachibowli-Hyderabad. Her research interests include the literature and history of Hyderabad, Partition Studies, women’s writing, and comparative literature.