Kolkata, WEST BENGAL / NEW DELHI :

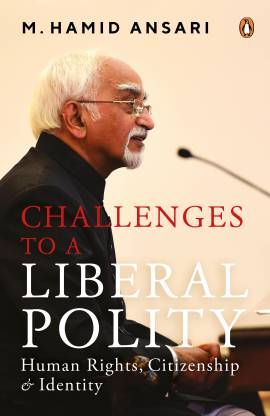

A collection of speeches and articles by former vice-president Hamid Ansari, offering engaging insights into our democracy.

For the past decade, public discourse in India has remained sharply focused on challenges to the liberal polity and the threats that have grown to human rights. Issues of citizenship and identity are entwined inextricably in this. It is in this context that Challenges to a Liberal Polity: Human Rights, Citizenship & Identity assumes not only topicality but also a significance that can be overlooked only at the readers’ own peril.

Hamid Ansari is a distinguished diplomat, academic, statesman and also, the often misused word, a public intellectual. He has, in his long career, worn many hats. He has served as the Indian ambassador to Afghanistan, Vice-Chancellor of the Aligarh Muslim University (AMU), Chairman of the Minorities Commission and the Vice President of India. Throughout his life, Ansari has never shied away from speaking his mind—bluntly if need be.

The author has, at times, been exposed to unfair criticism and deliberately humiliated by persons in high office who should have known better. When bidding him farewell, PM Narendra Modi was unnecessarily sarcastic—some thought gracelessly—by mentioning that Ansari had spent most of his diplomatic career in Islamic countries and perhaps he would be more comfortable now that he was relieved of the burden of the constitutional position to freely voice criticism of whatever he didn’t agree with. The PM conveniently forgot that the former vice-president served with distinction as India’s permanent representative in the United Nations and as Chief of Protocol when Indira Gandhi was the prime minister in an era of dynamic Indian diplomacy. But, let us not digress.

This volume is a collection of speeches, forewords and articles contributed by the author on subjects that overlap and cover a vast time span from the turn of the century to the present day. The introduction is stimulating and thought-provoking. It presents a distilled essence of state-of-the-art research in political science and Indian society. This prepares the readers for what is to follow.

The book is divided into three sections. The first section deals with human rights and group rights. The subsections or mini-chapters can be read profitably as independent essays. Of particular interest are the ones titled––‘India and the Contemporary International Norms on Group Rights’, ‘Minorities and the Modern State’ and ‘Majorities and Minorities in Secular India: Sensitivity and Responsibility’.

The second section is titled ‘Indian Polity, Identity, Diversity and Citizenship’. This is more substantial than the preceding segment and covers a range of topics that should engage readers with different interests and ideological orientations. Examples include ‘Identity and Citizenship: An Indian Perspective’, ‘Religion, Religiosity and World Order’, ‘Two Obligatory -isms: Why Pluralism and Secularism is Essential to our Democracy’. There are shorter pieces like ‘The Ethics of Gandhi’ and ‘The Dead Weight of State Craft’, ‘India’s Plural Diversity is Under Threat: Some Thoughts on Contemporary Challenges in the Realm of Culture’. How one wishes that these themes had been explored in greater detail.

To some it may appear that this is nitpicking, but this is the hazard of compiling a collection of comments and observations made on commemorative occasions such as inaugurating or concluding a seminar, a workshop or writing a short preface. Ansari is primarily a scholar, who is deeply distraught by the happenings around him and is restless to share his constructive thoughts and not just the distress and despair. The tone is always cautiously optimistic.

The concluding section deals with ‘Indian-Muslim Perception and Indian Contribution to Culture of Islam’. The essays on ‘Militant Islam’, ‘Islam and Democratic Principle’ and ‘India and Islamic Civilisation: Contributions and Challenges’ deserve to be read by all Indians, particularly the young. One may disagree with the author, but it is impossible to imagine that any meaningful dialogue can take place between the majorities and minorities in India without an understanding of how the ‘other’ thinks and perceives the world.

His convocation addresses delivered at Jamia Millia Islamia (where he taught) and the AMU (his alma mater) have a different flavour. The tone is personal and evokes shared nostalgia. The final essay is a review of India and muslim world.

The book has substantial end-notes that provide useful bibliographical information. One can flip through these pages to pursue the themes dealt in the book according to one’s own inclination and at leisure.

This book is for all. The general reader, who has no scholarly pretensions, too can turn the pages of this book with great pleasure. Many a time, the author peppers the prose with Urdu couplets that hook the reader to his line of arguments. One such piece is his Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed Memorial lecture. Most people remember this vice-president as the supine individual who signed on the dotted line with dimmer when Indira Gandhi declared Emergency at midnight. Ansari, however, has used the book brilliantly to make some hard- hitting comments that are im- possible not to take on the chin.

The chapter begins with: Yaad-e-maazi azaab hai yaa rab/ Chheen le mujhse hafiza mera (The memory of the past is torturous, O God/Take away my memory from me), and concludes with: “Can the amnesia, the compromises and the misconceptions of recent and not-so-recent past be overcome?” Yes, only if meaningful alternative is offered. We do stand at the crossroads.

source: http://www.newindianexpress.com / The New Indian Express / Home> Lifestyle> Books / by Pushpesh Pant / Express News Service / November 06th, 2022