Bhopal, MADHYA PRADESH:

Bhopal :

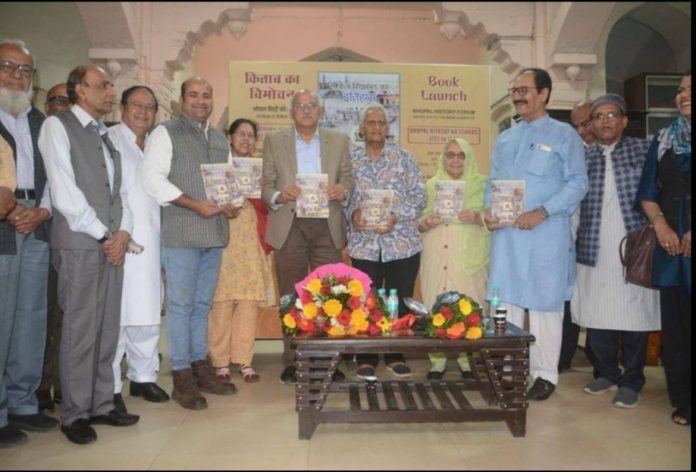

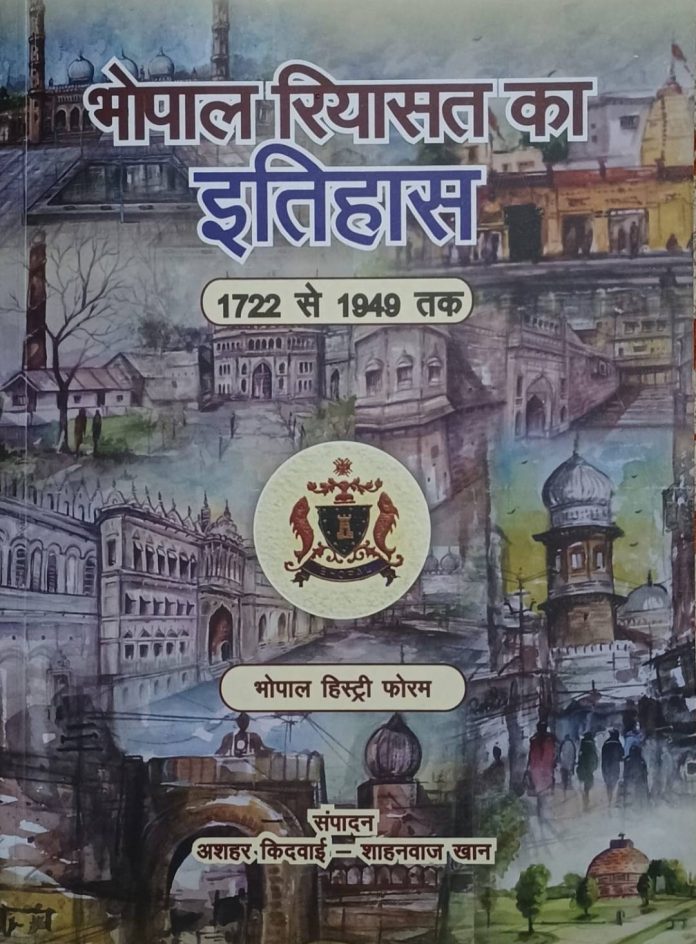

A book christened as “History of Bhopal Riyasat from 1722 to 1949” on the authentic history of Bhopal state was released at the historical Maulana Azad Central Library here the other day in a simple but impressive function amidst a host of enthusiastic intellectuals comprising of the young and the grey-haired both.

The 333-page book has been brought out by Bhopal History Forum (BHF). The Forum comprises of historians, writers, intellectuals and dignitaries of Bhopal. The Forum is working to save the old Ganga-Jamuni culture of Bhopal by connecting people from every section of the society with the youth and elders to save the history, art and culture of the princely state of Bhopal.

The main intention of the Bhopal History Forum in bringing out this book is to dispel many myths, fictions, fantasy, misinformation etc. about the rulers of Bhopal state ruled by its founder Dost Mohammad Khan and his descendants. A group of dedicated young and old mortals got together under the banner of Bhopal History Forum and established truth, authenticity and certainty of the facts lost in the face of parables and fabrications by vested interests to defame the rulers.

It was generally believed and heard about the princely state of Bhopal that it was merged into the Union Government of India in 1949 which is about two years after the country’s independence. This became a contentious issue between the people living here from the time of Independence with two narrations becoming prevalent in the masses which believed that the merger took place in 1949 while the other was convinced that it took in 1947 when India became free from the British yolk.

Bhopal State merged with Indian Union in 1947 Not 1949

However, Bhopal History Forum with its untiring efforts unravelled the truth with solid documentary proof. The BHF has published in the present book the document of merger of Bhopal State with the Union of India which was signed by Nawab Hameedullah Khan at 8:15 pm on 14th August 1947. Its basis is the Instrument of Accession. A photocopy of this document has been published in the book to establish their claim. The Nawab was asked to look after the administrative system until the constitution was framed. This document has the signatures of Nawab Hameedullah Khan and Lord Mountbatten, the Governor General of India. The Nawab had, however, requested Lord Mountbatten and the Government of India not to make this information public.

While BHF convener Adv. Shahnawaz Khan claimed that the merger movement was a movement for the merger of princely state of Bhopal into Madhya Bharat province. Even before this, the Bhopal state had been merged into the Union Government of India in 1947.

Meticulously crafted tome

Introducing “History of Bhopal Riyasat from 1722 to 1949” – a captivating exploration is aimed to revive forgotten stories and the voices of those who lived within the confines of Bhopaliyat. This meticulously crafted tome, launched amidst anticipation and scholarly fervour, is nothing short of a masterpiece. The book has been edited jointly by erudite historian Asstt. Prof. Ashar Kidwai and Adv. Shahnawaz Khan. The book transcends mere narration, offering readers an immersive odyssey through the corridors of time. With eloquence and insight, the book unfolds the rich tapestry woven from archival documents, letters, transcripts and eyewitness accounts; our journey goes far beyond history.

Putting their best foot forward the editors and contributors have negated the adverse and objectionable comments made by some right wing politicians and others from the cinema world that put the rulers of Bhopal in very poor light calling them names which are unprintable. While burning proverbial midnight oil to search, research and re-research through the historical records available in the National Archives of India, Bhopal Branch and Madhya Pradesh State Archives along with in some personal libraries and collections they dug up the truth to nail the adversaries spreading fabricated facts.

Meanwhile, the book’s launch ceremony was graced by Santosh Choubey, Chancellor of Rabindranath Tagore University, as chief guest and environmentalist Rajendra Kothari was also present as a special guest.

Many well-known personalities, including educationist and litterateur such as Dr. Razia Hamid, a well-known writer, Nisar Ahmed (Rtd. IAS), Mohammad Asghar, Assistant Director of National Archives of India, Bhopal Unit; Archivist Mirza Mumtaz Beg, Social worker Kalim Akhtar, Mukesh Verma, Chairman of Vanmali Srijan Peeth; Ms Ratna Wadhwani, Librarian of Maulana Azad Central Library, Bhopal; Zainuddin Shah, Secretary of Saifia College Society; Khalid Mohammad Khan, Rizwan Ansari, Syed Khalid Ghani, Sarwat Zaidi etc. (all members of BHF) along with other distinguished citizens were present on this occasion amongst others.

Tagore expressed regret to Bhopal Nawab

Speaking on the occasion Santosh Choubey narrated an incident related to Noble laureate Gurudev Rabindra Nath Tagore, who had come to Bhopal in 1931. He said that after his return to Calcutta Tagore wrote a letter to Nawab Hameedullah Khan thanking him for his warm hospitality and honour extended to him and his entourage which accompanied him. The letter has been published in the book. He, however, in the letter regretted that some persons in his entourage going beyond norms had accepted many valuable gifts presented to them by your courtiers while enjoying sumptuous food.

While Rajendra Kothari recalled that Bhopal had an identity because of its relationship with the Mewati family as Nazir Khan of Mewati gharana was the musician of Nawab Hameedullah Khan. He died in Bhopal and is buried here. This was revealed by Pandit Jasraj (28th January 1930 – 17th August 2020) who was an Indian classical vocalist, belonging to the Mewati gharana.

Book contains 48 articles by various authors

This book is divided into seven sections containing 48 articles by various authors with some rare pictures. The book is in Hindi and but has two chapters in Urdu also. In the book, quoting a photocopy of a letter, it is mentioned that Nawab Hameedullah Khan wrote a letter to Sardar Patel on 26th August 1947 asking him to merge his princely state with India. Apart from this, a photocopy of the Gazette notification regarding keeping holiday in Bhopal state on Independence Day, 15th August 1948 has also been published. There is also a photocopy of the order declaring holiday in the state of Bhopal to celebrate Gandhi Jayanti on 2 October 1948.

What truly sets this book apart is its ability to breathe life into historical figures and events, rendering them vivid and palpable. In sum, “History of Bhopal Riyasat from 1722 to 1949” is a tour de force that will enrapture both seasoned historians and casual enthusiasts alike. Its rich prose, meticulous research, and insightful commentary make it an indispensable addition to any library.

The book is available on Amazon; AISECT Publication, E-7/22, SBI, Arera Colony, Bhopal-462016 (Contact No. +91-8818883165).

source: http://www.muslimmirror.com / Muslim Mirror / Home> Books> Indian Muslim / by Pervez Bari / March 14th, 2024