Surat, GUJARAT / NEW DELHI :

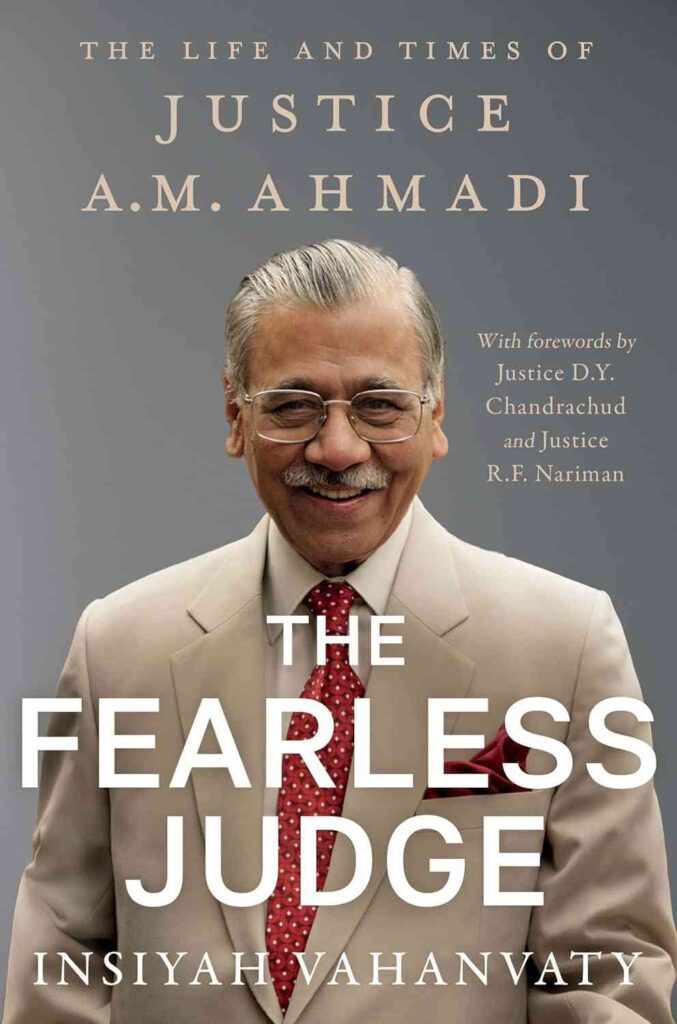

Insiyah Vahanvaty on revisiting the life of the formidable ‘Muslim’ judge who was her grandfather.

Being a Muslim judge in India is not easy. It has never been.

The Indian judiciary has long struggled with a lack of Muslim representation, with only four Muslim Chief Justices in the history of the republic. Currently, there is just one Muslim judge on the Supreme Court – another proof of this lack of diversity. It also indicates that another Muslim Chief Justice may be a long way off.

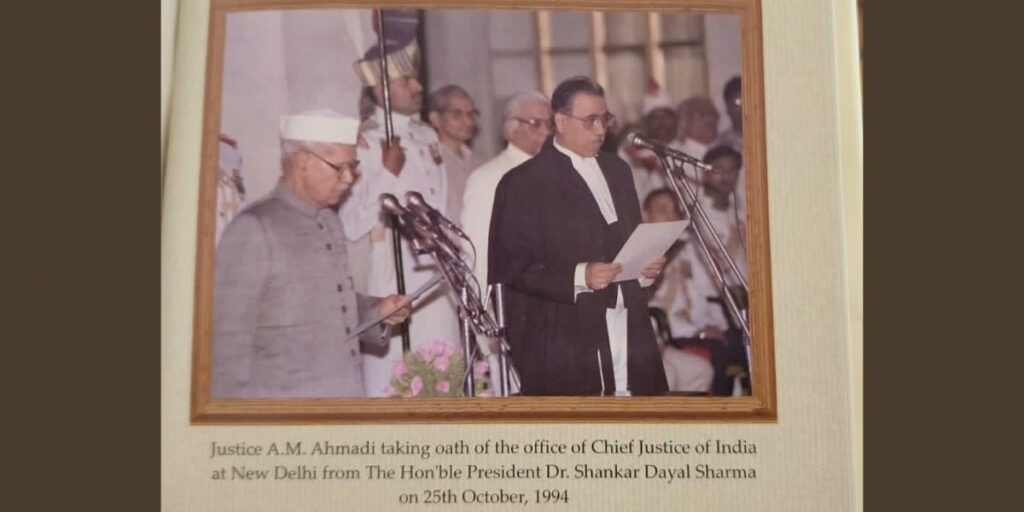

For me, the difficulties faced by Muslim judges have been witnessed through the life of my grandfather, Justice Aziz Mushabber Ahmadi, who served as Chief Justice of India from 1994 to 1997. That he was only the third Muslim to occupy this role is made starker by the fact that there has been only one more that succeeded him in the thirty years since.

When Aziz Ahmadi was appointed as a judge to the City Civil Court of Ahmedabad, he was 32 years old. Young and inexperienced, he knew that this appointment would make him the only Muslim judge on the bench; yet it had simply not occurred to him that his faith would suddenly become a matter of contention. When news of his elevation broke, it stirred up an unsettling, religiously charged atmosphere within legal and administrative circles. Bar Associations across the state of Gujarat united and called for a strike against his appointment, boycotting Ahmadi’s court. Communally charged allegations flew thick and fast with his appointment questioned in the legislative assembly. Concerns about his young age and fitness for the role were voiced. In the end, however, his appointment held – and Aziz Ahmadi began an extraordinary judicial career that would span three decades, culminating in the highest office of the Indian judiciary.

Yet, it would never be free of challenges.

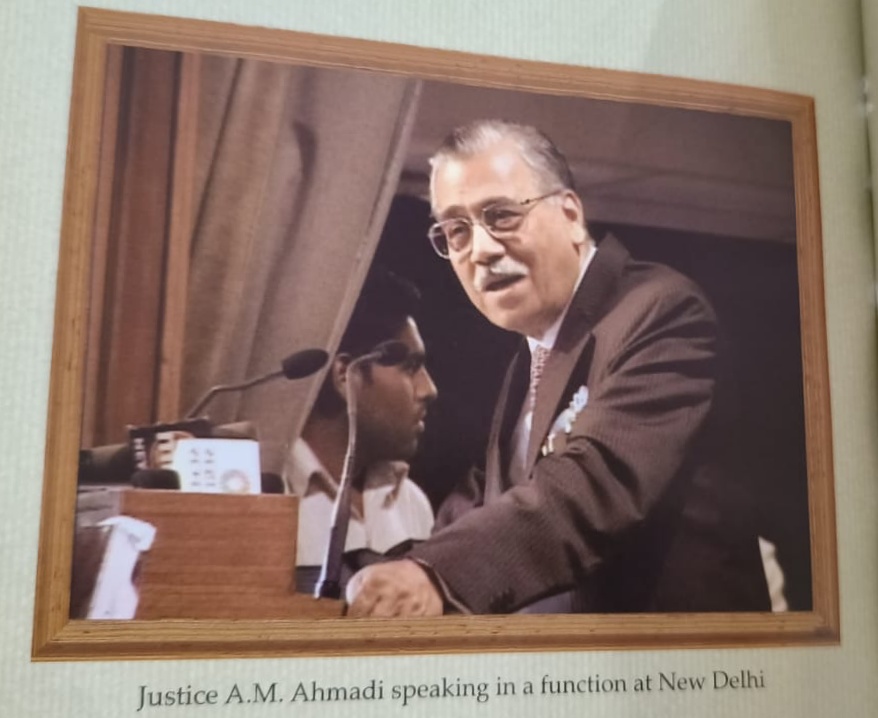

Twenty-four years later, when his name was proposed for elevation to the Supreme Court of India in a closed-door meeting, a prominent member of the Bench hesitated, saying, “But he is a Muslim. Can we trust him?” And when he retired, Justice Ahmadi faced allegations of favouring the appointment of Muslim judges to High Courts and the Supreme Court. Unperturbed, he responded to these saying, “Such an allegation every Muslim Chief Justice, I suppose, has to face.” Although he did not voice it then, he felt a deep disappointment in witnessing such prejudice even in the highest offices of the country.

And yet, he wore his life with a remarkable lightness, with his easy laugh and mischievous wit. It was almost as if he was determined not to allow these experiences to make him bitter or dampen his natural optimism. Ironically, it was perhaps these very experiences that fuelled his commitment to secularism and tireless advocacy for the separation of religion and state.

My first memory of these values was during a particularly turbulent chapter in Indian history when I was just ten years old.

The year was 1992. The Babri Mosque had just fallen. A word which I had never heard before was now coming up every day at our dinner table. Kar seva. The television at home stayed locked on the news channel all day. My grandfather’s disappearance from family life, his secretaries rushing to and from the office with pens and notepads in hand, and worried family conversations about the future of the Indian Muslim marked those days.

But despite his inner turmoil, my grandfather maintained an outward calm, his composed demeanour never betraying the storm within. As ever, Justice Ahmadi, when distressed, would retire to his haven, his work. I knew the enormity of his mental anguish only because of the extent to which he did this. Those days, he emerged only for meals and slept for less than five hours a day. Pacing on the carpeted floor, he fought the numbness in his legs from hours spent hunched over his files, fuelled by endless cups of black tea.

It was only later that I learnt of his dissent in Ismail Faruqui vs Union of India – a challenge to the Acquisition of Certain Area at Ayodhya Act 1993 which was an attempt by the Central Government to gain control of administration and maintenance of the Ram Janma Bhumi-Babri Masjid structure along with its premises. In his view, validating the Ayodhya Act would effectively condone the trespass and destruction that occurred, with no consequences for those involved – especially as the effect of the Act would require pujas to continue at the site while failing to address the right of Muslims to offer namaaz.

It was while writing The Fearless Judge and going through his draft memoirs that I learnt of the immense strain my grandfather was under at the time to accept the majority judgement. But he would not succumb. Risking the ire of both, the incumbent Chief Justice as well as the executive, he knew that such a stand could come at great personal cost. Yet, he stood firm in this test of integrity, refusing to give in. Ultimately, he and Justice Bharucha dissented from the majority view.

Citing the Act to be unsecular and constitutionally unfit, the dissenting judgement authored by Justice Bharucha stated, “When…adherents of the religion of the majority of Indian citizens make a claim upon and assail the place of worship of another religion and, by dint of numbers, create conditions that are conducive to public disorder, it is the Constitutional obligation of the State to protect that place of worship and to preserve public order…To condone the acquisition of a place of worship in such circumstances is to efface the principle of secularism from the Constitution.” Once retired and therefore released from the bounds of propriety and decorum, my grandfather would speak freely about the regrettable and unlawful demolition of a place of worship – and the subsequent erosion of secularism in India.

The demolition of the mosque sent shockwaves throughout the country, prompting the Union government to dismiss state governments in a panic. This led to the landmark case SR Bommai vs. UOI, which addressed the limits of central authority over states. Because these dismissals were in response to the violence following the Babri Masjid demolition, the court also examined secularism as a key element of the Constitution’s basic structure. Justice Ahmadi wrote a separate 37-page judgment emphasizing the need for accommodation and tolerance toward vulnerable groups. Quoting Mahatma Gandhi to highlight the importance of the separation of religion and state, he wrote, “I swear by my religion. I will die for it. But it is my personal affair. The State has nothing to do with it. The State will look after your secular welfare, health, communication, foreign relations, currency and so on, but not my religion. That is everybody’s personal concern.”

Despite his deep understanding of the discriminations that Indian Muslims face in every sphere of life, he encouraged the community to resist the temptation to view itself from the lens of victims of prejudice; rather to focus on empowerment through education. Addressing the Muslim community, he said, “It is high time that we stop living in the past and start living in the present and work for a brighter future. We have to mould our own destiny – mustaqbil, no one else can do it for you. The only sure way is through education.”

A firm and vocal advocate for equality of opportunity until the end of his days, Justice Ahmadi remained troubled by the lack of diversity in the judiciary at all levels. With Muslims making up nearly 15 per cent of the population yet holding alarmingly few judicial positions, this lack of representation remains concerning to this day, raising questions about fairness and inclusivity. The implications of this imbalance are significant: Judges from diverse backgrounds ensure the judiciary mirrors the society it serves, bringing different perspectives and more fair-minded decisions. In turn, this shores up public trust in the legal system.

And as Justice Ahmadi put it so succinctly, “The judiciary has neither the purse nor the sword; its only shield is the trust of the people in the judicial process.”

source: http://www.scroll.in / Scroll.in / Home> Talking Books / by Insiyah Vahanvaty / September 30th, 2024