Gangauli (Ghazipur District), UTTAR PRADESH / Mumbai, MAHARASHTRA :

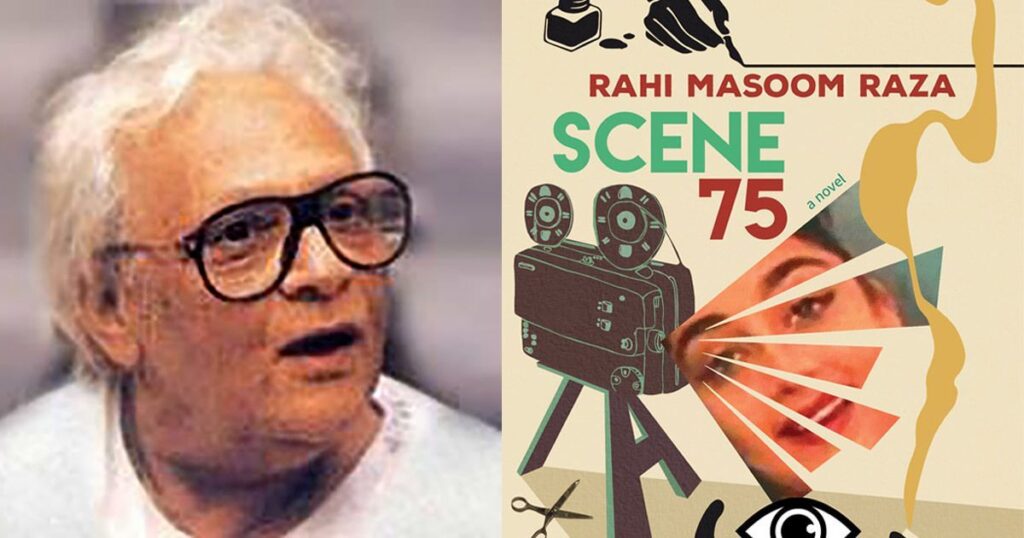

Edited excerpts from an essay by the translator of the renowned writer and poet’s novel ‘Scene 75’.

The first thing I read when I opened Scene: 75 was the ‘Vasiyat’ (‘Will and Testament’). I was so moved, I kept going back to it until, finally, I took a picture and pasted it on my laptop screen so that I could see it every time I opened my computer. At that time, all I knew about Rahi Masoom Raza was that he was a highly respected poet and novelist, though his success as a writer of Hindi films had somewhat overshadowed his literary accomplishments. But what eventually eclipsed everything – at least in the popular imagination – was that he was the writer of the majestic dialogues for the blockbuster TV series Mahabharat. Over time, as I read more and more about him and his life, I realized that the ‘Vasiyat’ was a true mirror of the kind of man he was: an unsparing critic of fundamentalists and hypocrites of every hue, with deep roots in his hometown in Ghazipur, Uttar Pradesh. All this found reflection in his writing, which also had a strong dose of biting humour that made you laugh out loud and wince at once.

Satire about the stars

Scene: 75 itself is a darkly funny, surreal novel in which Rahi sahib casts an unsparing, satirical look at the Hindi film industry of the 1970s and also writes about Hindu–Muslim relations with his customary blistering honesty. The book begins with Ali Amjad, a struggling scriptwriter from Benares, trapped in a lonely Bombay flat, and ends with him still trapped in that lonely flat. But in the middle is a teeming, intertwined, untidy throng of cynical and manipulative characters and their equally fantastic stories, narrated with a no-holds-barred candour by Rahi sahib. Unscrupulous film producers and ambitious clerks rub shoulders with wealthy lesbians and bigoted middle-class social climbers. There are few lovable characters. When I finished the novel, I realized that the only character I cared for was Ali Amjad (Rahi sahib himself, I think) – nevertheless, all of them held my undivided interest. They made me laugh even as I shook my head in disbelief at their doings.

Rahi sahib wrote several novels between 1966 and 1986, the best-known of which is the first one, Aadha Gaon, a vivid, true-to-life depiction of the Shia community in a village, Gangauli, in the United Provinces at the time of Partition. The lives of Muslims in India and their relationship with Hindus formed the central motif in many of Rahi sahib’s works, including the brilliant Topi Shukla (1968) and Os Ki Boond (1970). Even in Scene: 75, this fraught relationship is thrown into sharp focus. Ali Amjad is hunting for a house and can’t find one because he is a Muslim. He is asked to pretend he’s a Sindhi by a prospective landlord, but Ali Amjad refuses:

“‘I am a Muslim and I also work in films,’ Ali Amjad said. He thought it was necessary for him to say this. He was not a religious man. He didn’t believe in Allah. He didn’t do namaz. He didn’t fast during Ramzan. He was an uncompromising critic of organizations like the Muslim League and the Jamate-Islami … But he was not ashamed of the fact that he had been born into a Muslim family. And he did not want to insult himself or his country by hiding his name and identity.”

Dialogue with cinema

Rahi sahib came to Bombay in 1967 to try his luck in Hindi films, and lived and worked there until his death in 1992. He wrote the script and dialogues for over 300 films, including enduring hits such as Mili (1975), Main Tulsi Tere Aangan Ki (1978), Gol Maal (1979), Karz (1980), Lamhe (1991) and many others. But he is best remembered for his dialogues for the 94-episode mega TV series, Mahabharat, in the late 1980s. There’s an interesting story about how Rahi sahib took up this challenging project. According to his close friend and colleague at Aligarh Muslim University (AMU), Kunwarpal Singh, when filmmaker B.R. Chopra requested Rahi sahib to write the dialogues, he declined, saying he didn’t have the time. But B.R. Chopra went ahead and announced Rahi sahib’s name at a press conference anyway. In no time, letters of opposition from self-styled protectors of the Hindu faith arrived: Were all Hindus dead that Chopra had to give this task to a Muslim? Chopra promptly forwarded the letters to Rahi sahib. Ever the champion of India’s syncretic culture, Rahi sahib called Chopra the next day and said, ‘Chopra sahib! I will write the Mahabharat. I am a son of the Ganga. Who knows the civilization and culture of India better than I do?’

He was born in 1927 in Ghazipur in eastern Uttar Pradesh, on the banks of the Ganga, and retained a deep attachment to his childhood home all his life. (Poet and lyricist Javed Akhtar said in an interview that Rahi sahib found a way to introduce his hometown into every conversation, even if it was about the United Nations Security Council.)

After finishing his school education in Ghazipur, Rahi sahib went to Aligarh for higher studies and did a doctorate in Hindustani literature. By the early 1960s, he had got a job as an Urdu lecturer in AMU. Javed Akhtar, in an interview, says, ‘Rahi sahib was a cult figure [on the campus]. He enjoyed a huge fan-following among the students, boys and girls both, owing to his charming and stylish persona. His admirers would walk by his side whenever he roamed [around] in the campus. He would limp a bit, for he had been affected by polio in his childhood, but his elegant sherwani, which he would never button, and the classy kurta, would make it clear that he was no ordinary man. He was a star.’

Moving to Mumbai

If things were going so swimmingly in Aligarh, why did he uproot himself and shift to Bombay? According to Kunwarpal Singh, this decision was triggered by his wedding to Nayyar Jahan in 1965. She had been previously married, but Rahi sahib fell in love with her and, despite opposition, went ahead and made her his wife. A fullblown scandal erupted and Rahi sahib lost his job at AMU (though Kunwarpal Singh says that the scandal merely gave his rivals and foes an excuse: they had always been opposed to his attempts to introduce Hindi courses in the Urdu department and vice versa).

Aadha Gaon had been published by then. It had brought him renown but was of no help in securing a livelihood. Nadeem Khan, Rahi sahib’s son, says that it was filmmaker Ramesh Chandra, an Aligarh acquaintance of Rahi sahib’s (also the older brother of actor Bharat Bhushan), who invited him to come to Bombay and try his luck in the film industry.

And that’s what he did. Initially, there was no work. He tided over that difficult period with the help of his writer friends like Kamleshwar (who was editing the magazine Sarika then) and Dharamvir Bharati (who was editing Dharmyug). His writings were published in their magazines; often they paid him in advance. But slowly, he began establishing himself in the film industry. He worked closely with film-makers such as Raj Khosla, B.R. Chopra, Yash Chopra, Hrishikesh Mukherjee and others. He became acquainted with the art of writing dialogues. Kunwarpal Singh recounts how once Rahi sahib had to write the dialogues for a Raj Khosla film. When the latter came to read the script, he kept saying, ‘Kya baat hai! Bahut khoob!’ as he turned the pages. At the same time, he kept cutting the dialogues. In the end, he kept just two or three lines out of every two pages. Rahi sahib learnt his lesson – in cinema, you don’t need verbosity; pages of dialogue can sometimes be communicated through a single close-up on screen. Over time, he became a consummate practitioner, winning two Filmfare Awards for Best Dialogue (for Main Tulsi Tere Aangan Ki and Mili).

Nadeem Khan remembers how he got his third award. Rahi sahib had written the dialogues for Lamhe and was very disappointed when it performed poorly at the boxoffice. He was proud of the work he had done in the film and had hoped for a Filmfare Award. But soon after Lamhe released, he passed away. He was just 65. Not long after that, Nadeem Khan, who was then working as the cinematographer for a Rakesh Roshan film, King Uncle, got a call from Filmfare. Rahi sahib had won the Best Dialogue Award for Lamhe posthumously. Khan remembers going to the function and collecting the award on his behalf. Jeetendra, the actor, was on stage and started crying. Khan says he felt his eyes welling up too. ‘As I came down, there was B.R. Chopra on one side and Yash Chopra on the other. Both kept hugging me,’ he recalls. ‘I went home and put the award in front of Rahi sahib’s photograph.’

The masterful dialogues for Mahabharat and the decision to make Samay (Time) the narrator were what elevated the series to another plane. The production values and acting left much to be desired, but the powerful dialogues by Rahi sahib made the show the astounding success that it was. He coined new words, such as ‘Pitashri’ and ‘Matashri’, which became so popular that people thought this was how characters must have spoken in ancient times. The truth is that Rahi sahib adapted these words from the way family members are addressed in Urdu – ‘Ammijaan’, ‘Abbajaan’ and so on.

Nadeem Khan says that those years of writing the Mahabharat took their toll on Rahi sahib: ‘He aged fifteen years in that time. It was very stressful – he couldn’t afford to take one wrong step,’ he says. ‘After Mahabharat, he was supposed to write another TV show, Om Namah Shivay (he was a great Shiv bhakt). But that was not to be.’

Excerpted with permission from Scene 75, Rahi Masoom Raza, translated by Poonam Saxena, HarperCollins India.

source: http://www.scroll.in / Scroll.in / Home> Book Excerpts / by Poonam Saxena / December 30th, 2017