Bhopal, MADHYA PRADESH :

Indira Iyengar’s book flounders on history, making some foundational conclusions untenable.

Some books need to be read because they are likely to tell you things you have always wanted to know. Some stories need to be told because they make for riveting narratives or expand your frontiers of knowledge in exciting and dramatic ways.

It is with such noble (and hopeful) intentions that one embarks upon The Bourbons and Begums of Bhopal: The Forgotten History despite its awkward size and substantial weight. In its size and appearance, it is is an unfortunate mix of a book with pictures and copious amounts of running text: too large to carry while travelling and not sufficiently picturesque to qualify as a coffee-table book. Its contents prove to be an awkward mix too, floundering between academic research and family lore.

Indira Iyengar,

Niyogi Books Private Limited, 2018.

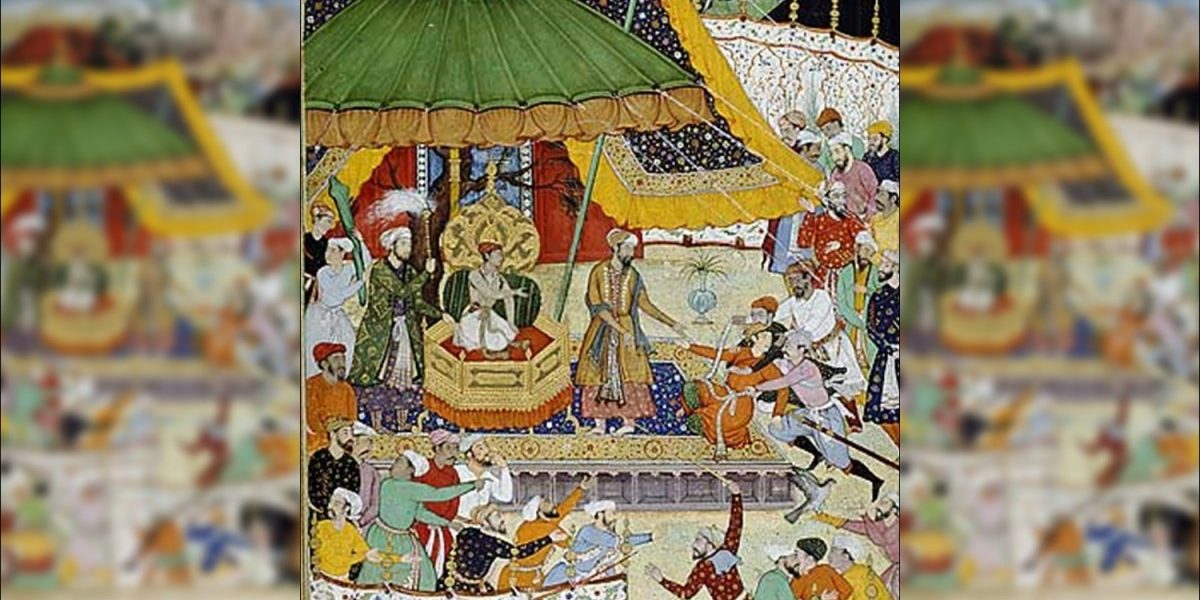

Indira Iyengar’s tale is part family history, part archival research and part anecdotal memoir. It opens with a disarming admission: ‘I am no historian, but I have a story to tell.’ Iyengar’s mother, Magdaline Bourbon traced her lineage to Jean Philippe de Bourbon who left his native France to arrive in Mughal India, sought and received employment in Emperor Akbar’s court, was actively involved in Akbar’s meeting with the Jesuit priests from Goa. For his services, Akbar is said to have gifted him a small principality, Shergarh near Narwar in present-day Madhya Pradesh and the sister of his Christian wife, an Armenian woman (Portuguese by some accounts) by the name of Juliana who apparently also served as a doctor in Akbar’s harem. Thus began the Bourbon line in India which spread its roots from the Mughal court to the princely state of Bhopal where the descendants of this first Bourbon eventually settled down. Being neither Muslim nor Hindu the Frenchmen were viewed as unbiased and loyal to their masters. The stories of their swashbuckling past and alleged purported ‘royal bloodline’ no doubt added to their mystique.

While Iyengar is at pains to establish her ancestor’s descent from the Bourbons of Navarre, historians are divided as to whether Jean Philipe was indeed from the royal house of Bourbon or simply a fugitive Frenchman, a mercenary who found name and fame in distant India, established a lineage and bestowed a legacy. Iyengar seems to be working on the principle that her mother’s version of the family history should suffice and she, as the custodian of that family history, is obligated to tell the story. ‘My mother’s narration of the family was also very interesting,’ Iyengar writes, ‘and I feel it needs to find a place in recorded history’. It is this assertion that proves to be problematic. For, had it been told as a colourful yarn with anecdotes and family portraits or even bits and pieces of trivia and family lore it could have been a charming story – as history it is on decidedly shaky grounds.

Also, while Iyengar’s research in the archives of the Agra Archdiocese may well establish the role of her French forefathers in various administrative capacities, it does not satisfactorily establish Jean Philippe’s link with Duke Charles III de Bourbon (1490-1527), also known as Connetable de Bourbon. The earliest account of Jean Philippe she is able to offer is by Madame Dulhan Bourbon, wife of Balthazar Bourbon; this comes in the form of a testimony made to a British general. Coming from a family member, that too as late as the late-19th century, it carries dubious weight at best. All other accounts, by missionaries, are in the nature of hearsay, urban legends that acquired veneers of half-truths with each telling. Jean Philippe himself is said to have presented a document to Jahangir in 1605 or 1606, according to Iyengar, stating that he was the son of Charles Connetable de Bourbon and that he had to flee France after arranging a mock funeral for himself. Since such a document does not exist, we can only rely on the author’s mother, Magdaline Bourbon’s memory of a ‘certain priest from Bombay’ who possessed the Bourbon family records that were subsequently ‘lost with time’. Shazi Zaman who has recently written a well-researched book on Akbar and has a detailed account of Akbar’s contact with the Europeans who visited his court, makes no mention of a Bourbon.

While Jean Philippe’s relationship with the House of Bourbon may be in dispute, Iyengar’s research in the archives of the Agra Archdiocese shows that there existed a certain Jean Philipe de Bourbon, who was married to a certain Bibi Juliana (referred to in later Jesuit accounts as Dona Juliana Dias da Costa) who helped build the first Catholic church in Agra in 1588 on land gifted by Akbar. Jean Philipe is said to have died in Agra in 1592 leaving behind two sons one of whom, according to Iyengar, was in charge of the seraglio. At the time of Nadir Shah’s invasion, the Bourbons left poor, ravaged Delhi and the clan, by now comprising 300 men and women, sought refuge in the family estate in Shergarh and thence began the southern sojourn of Jean Philippe’s descendents. Mamola Bai, the first woman ruler of Bhopal, offered Salvador Bourbon the position of general in the Bhopal state army. Salvador married a certain Miss Thome and the family then embarked on a long innings serving as confidantes, generals, even Prime Ministers to the Bgeums of Bhopal.

Already carrying two names, a European and a Muslim one, the Bourbons began to wear Bhopali dress and live like the local nobility. However, the fleur de lis in their coat of arms never failed to remind them and their local patrons of their royal past in distant France.

Rakshanda Jalil is a writer, translator and literary historian.

source: http://www.thewire.in / The Wire / Home> Books / by Rakshanda Jalil / October 05th, 2018