BENGAL :

As a Muslim reformist, her activism was neither half-baked nor exclusionist, yet little is known of her meaningful contributions to society.

Sometimes when wars are long and without any imminent hope of triumph or an end, it’s best to count on the smaller victories. Such as the taking down of Omprakash Mishra’s misogynist cringe-pop video or Uber apologising for their presumptuous and sexist offer on “Wife Appreciation Day” or Hulu’s The Handmaid’s Tale bagging the Emmy for “Best Drama Series” leaving behind popular shows like Westworldand Stranger Things.

The Handmaid’s Tale is to feminists what the BJP manifesto is to Arnab Goswami. Though Margaret Atwood’s evergreen dystopian thriller published in 1985 was one of its kind, it wasn’t the first. Eighty years before that, Begum Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain published her feminist utopian fantasy Sultana’s Dream, a novella investigating the ironies of a technologically advanced, gender-reversed India (one where men were confined to the “zenana” — the part of a house for the seclusion of women, or as Rokeya terms it, the “mardana” — imagined in the dreams of a woman named Sultana.

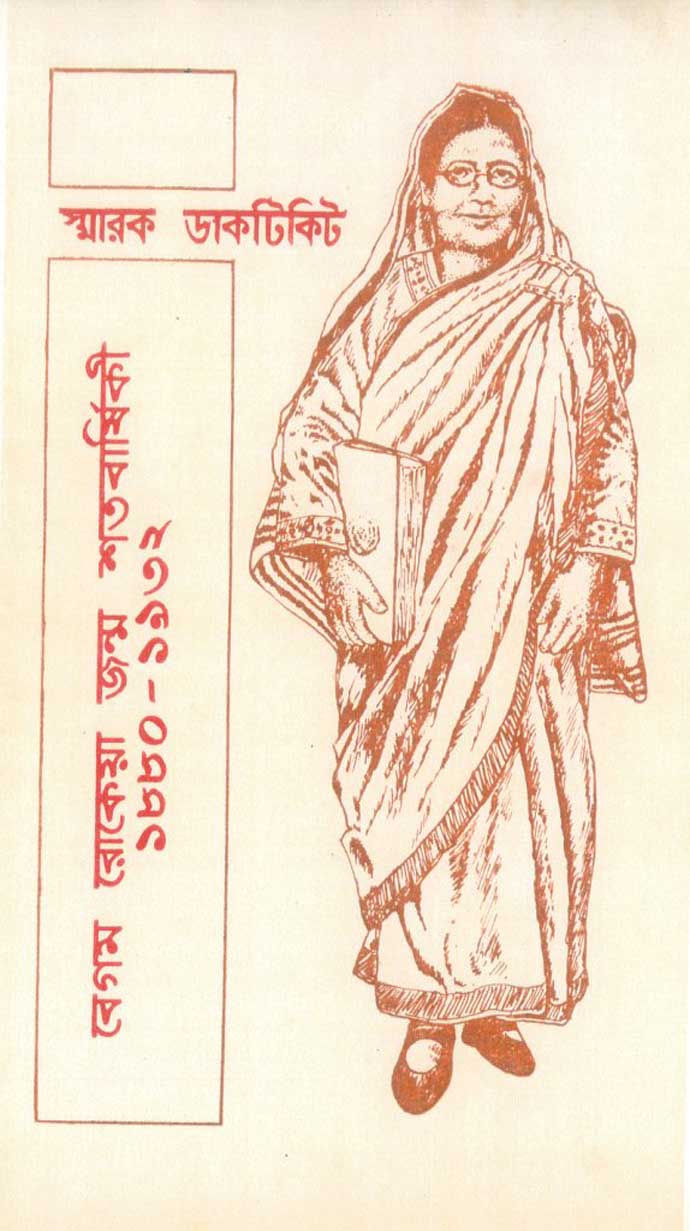

Born in 1880 to a wealthy Zamindar family in Pairabondh (present Bangladesh), Rokeya Begum was an educationist, writer, social activist and effectively, India’s first Bengali Islamist-feminist. While Savitri Phule and Pandita Rama Bai re-emerged through the obliterating clouds of India’s redacted history-telling, the narrative on Rokeya’s work remains shrouded, at least, in India.

Her father, an orthodox Muslim, persisted that the women maintained purdah and allowed them to be educated in Arabic (only) to enable them to read the Quran. Rokeya and her sister Karimunnesa, learned Bengali and English at the behest of their supportive brothers, who educated them on the sly. Perhaps this phase of her own life contributed amply to her tenacious belief that the lives of Muslim women could not be ameliorated without proper education. Added to that was her own sister who remained a key inspiration for Rokeya’s writings and her social work.

Karimunnesa, a seasoned poet, had been married off before the age of 15, putting what might have been a lucrative future to an abrupt end. This had further consolidated Rokeya’s faith in educational and individual rights for women — chiefly Muslim women, who, in that era, lived like showpieces in a glass casket but with an iron curtain.

With this line of thought and the support of her husband (Sakhawat Hossain, whom she was married to at the age of 16 and who died in 1909) and the money he had set aside, Rokeya went on to establish Sakhawat Girls Memorial High School, five months after his demise.

She started the school in Bhagalpur (a majority-Urdu speaking area in erstwhile East Bengal) with merely five students and was forced to shift the school to Kolkata in 1911 due to property feuds with her husband’s family. It remains one of the city’s most popular schools for girls and is now run by the state government of West Bengal.

In 1916, she founded the Anjuman-e-Khawateen-e-Islam (Islamic Women’s Association), which was her other organisational contribution to Bengali Muslim women. Through this organisation she offered financial and educational support to downtrodden Muslim women, over and above raising public opinion regarding the issue of Muslim women’s rights. That Rokeya was way ahead of her times finds semblance in the curricula of the school she established, which included physical and vocational training in an attempt to arm women with financial independence. She coined the term “manoshik dashhotto” or mental slavery, referring to the absence of individuality that pervaded the entire gamut of Muslim women and attributed it as the root cause for their subjugation. This rings true even today.

A century ago, Rokeya approached her adversaries with a wit and logic that is hard to find in today’s generation (which appears to be self-deprecatingly volatile). Insightfully, Rokeya tapped into the quintessential Muslim male ego and inversed it to men’s disadvantage, instead of directly antagonising them with liberal arguments.

She writes, “The Muslim society is paying a greater price for the lack of any system of education for their women. I have been informed by a reliable source that some educated Muslim youths of well-to-do families are setting conditions that if they can’t find educated Muslim women, they will not marry. They even threaten to become Christians and marry someone from that community if they fail to find educated Muslim women.”

Critics might question the ethic behind this approach, but the truth is, even now, “the threat to minority identity” continues to be the most veritable impediment to the realisation of Muslim women’s rights.

Keeping this in mind and the socio-politico environment of that era, perhaps by playing on their fears was not only ingenious but also the only way out.

In 1926, when she was invited to chair the Bengal Women’s Educational Conference, she said, “Although I am grateful to you for the respect that you have expressed towards me by inviting me to preside over the conference, I am forced to say that you have not made the right choice. I have been locked up in the socially oppressive iron casket of ‘porda’ for all my life. I have not been able to mix very well with people – as a matter of fact, I do not even know what is expected of a chairperson. I do not know if one is supposed to laugh, or to cry.”

Having lost her husband early and her two children who died at infancy, Begum Rokeya was not just subjected to scathing criticisms for her views but also faced unforgiving social exclusion. Despite the variegated hindrances she faced, in lieu of her gender, her community and the very fabric of the milieu that she had set out to change, she worked tirelessly and fearlessly to carve a way out for many Bengali Muslim women like myself.

Begum Rokeya died on December 9, 1932, and up until 11pm on December 8, 1932, she was working on an unfinished article titled, “Narir Odhikar“, which translates to women’s rights. The over-arching principle that governed her literary and social work was feminism and through it she heralded the discourse into Bengal. As a Muslim reformist from that era, Rokeya’s activism was neither half-baked nor exclusionist as the classist and sexist Aligarh movement led by Syed Ahmed Khan, yet little is known of her meaningful contributions to society. Today, Rokeya’s memory is as fleeting — even for her benefactors — as Sultana’s dream.

source: http://www.dailyo.in / Daily O / Home> Variety / by Suman Quazi / September 21st, 2017